Today’s record-high market prices are renewing interest in leasing beef cows. Doing so allows a rancher to run more cows without the added capital investment. Meanwhile, outside investors can gain a potential return on investment capital, plus a tax advantage from the cow depreciation. Cow leasing, if done properly, can be advantageous to both parties.

A common question I get on cow leasing is how the calf crop should be shared. In other words, what’s an equitable lease arrangement?

A typical cow lease is where one partner owns the cows and perhaps the bulls, while the other partner provides facilities, feed and labor. I’ll refer to the outside investor as the “cow owner,” and the partner running the cows as the “working rancher.”

The cow owner gets the cull-cow income, while the owner of the bulls gets the cull-bull income. Typically, the cow owner wants total control of the genetics of the herd, so the cow owner typically owns the bulls. This, however, is negotiable in the lease.

Here’s my three-step process for setting up an equitable beef-cow lease. In this example, I’ll use my 2014 beef-cow budget for eastern Wyoming and western Nebraska.

Step 1: Assemble the herd production facts for the beef cowherd producing 2014 fall-weaned calves.

The partners should never mix replacement heifer development into the beef-cow lease. It’s a bookkeeping nightmare, and someone typically gets taken. I recommend that heifer development be contracted out to a third party, with heifer development the sole responsibility of the cow owner.

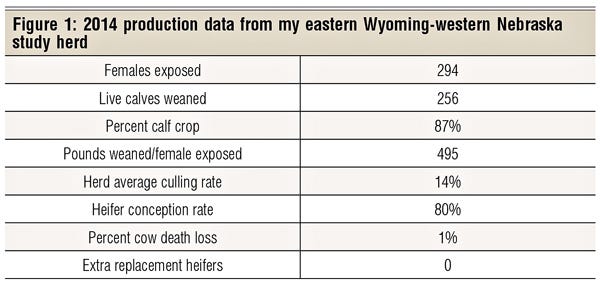

My study herd’s production data is summarized in Figure 1. This herd weaned 256 live calves in fall 2014 for an 87% calf crop. The herd’s average fall-2014 weaning weight was 584 lbs. for steer calves and 554 lbs. for heifer calves. This generated 495 lbs. of weaned calf per female exposed.

The herd’s average culling rate was 14%, and the average heifer conception rate was 80%. Cow death loss was 1%. These are the minimum production records I recommend for any leased beef cowherd.

As mentioned before, the cow owner gets the cull-cow income, as well as any inventory changes (positive or negative) and all beef-cow depreciation. Generally, the cow owner also provides all the preg-checked replacement heifers.

In some leases, the working rancher provides the replacement heifers, as this is one way for the working rancher to slowly gain investment control of the total herd. In about seven years, the entire herd will be the working rancher’s. This works especially well when the cow owner is a retiring rancher who wants to sell his cowherd over time in order to reduce his income-tax liability on the sale.

The owner of the bulls gets the cull-bull income and buys all replacement bulls.

The upper limit on acceptable cow and calf death loss can be set in the lease agreement to encourage proper management by the working rancher to protect the cow owner’s capital investment. Thus, cow losses up to that limit are the cow owner’s responsibility. Losses above that threshold are instead charged to the working rancher. This is negotiable at the time the lease is drawn up. A suggested standard is 1%-2%.

Deciding who absorbs calf losses can also be negotiated. One suggestion is that losses up to 8% might be shared by both partners, and losses beyond that figure might go to the working rancher only. Again, this is done to encourage good management and should be negotiated in the lease agreement.

Step 2: Prepare a full-cost economic budget for the leased herd.

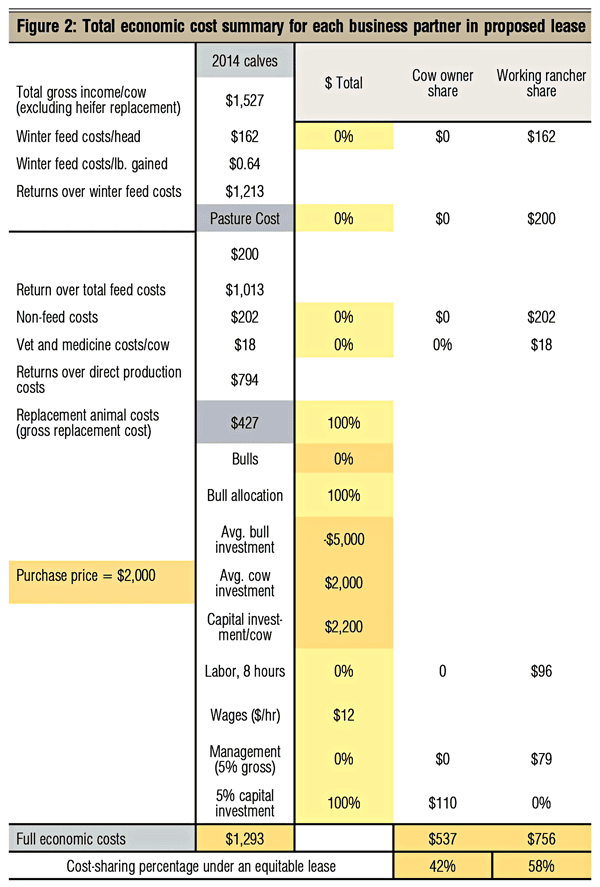

The key, and more difficult, question behind a successful lease agreement is, “What’s a fair and equitable division of the herd’s weaned calf income?” I believe an equitable lease divides the calf crop into the same proportions each partner contributes to the full economic costs of the herd.

These full economic costs are based on local pasture-rental rates, fair-market value of the farm-raised feeds, annualized costs of assets used by the cowherd, and the out-of-pocket costs of running the herd. Let’s calculate the full economic costs for the study herd.

Production expenses need to be allocated on a “full economic cost basis.” This includes:

an interest charge for investment capital,

a labor charge for all labor used in the cowherd,

a management charge for running the cowherd.

My study herd’s full cost summary is presented in Figure 2. Each major cost category is allocated to either the cow owner or to the working rancher. Routine production costs tend to be allocated to the working rancher. Labor cost is based on eight hours/cow, valued at $12/hour. Management cost is figured at 5% of gross income. Investment capital is figured at 5% of current market value.

Cowherd depreciation, cow death loss and bull replacement are totaled in the “replacement animal cost” category and are allocated to the cow owner. The herd, in this example, ends the year with the same number of preg-checked females as it started the year; thus, there is no inventory change.

Of the full economic costs, 42% are allocated to the cow owner and 58% to the working rancher.

Step 3: Determine the equitable lease.

Given this analysis, what’s an equitable lease? My analysis suggests a 58/42 lease is equitable, but I’d round it off to 60/40, with the working rancher getting 60% of the calf crop income and the cow owner getting 40%. Which partner gets steer calves and which partner gets heifer calves is negotiable. Another option is for the partners to divide the sale-barn receipts from the calves 60/40.

Finally, put the lease agreement in writing. The lease period should run from weaning date one year to weaning date of the following year. It’s also important to define and document the termination procedures before signing the lease.

I suggest a two- or three-year lease, with right of renewal under agreement of both partners. Use a lawyer to draft the final lease, with the termination procedures spelled out clearly in writing for both parties.

While legal battles are infrequent, they generally come about due to lack of a written termination agreement, or a lease year ending other than at weaning time.

Do your homework in developing a beef-cow lease and it can be a win-win situation for both parties.

Harlan Hughes is a North Dakota State University professor emeritus. He lives in Kuna, ID. Reach him at 701-238-9607 or [email protected].

You might also enjoy:

80 Photos Of Our Favorite Calves & Cowboys

Why The Cattle Market Is At A Critical Juncture

Cornstalk Grazing Offers Potential For Winter Cattle Feed Savings

60 Stunning Photos That Showcase Ranch Work Ethics

Producers Must Act Now To Save Their Beef Checkoff Program

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like