Rehydrating a scouring calf is critical for long-term productivity.

March 1, 2018

True or false: The No. 1 killer of calves in the first weeks of life is a gut infection.

Answer: It’s both true and false. That’s because it’s generally not the gut infection that actually kills the calf. It’s the dehydration and subsequent electrolyte imbalances, acidosis or shock caused by the diarrhea. The infection causes the scours, which causes the dehydration and associated problems, which cause death.

Dehydration, loss of electrolytes and decrease in blood pH (metabolic acidosis) are the three biggest problems with scouring calves, says Geof Smith, a large-animal veterinarian with the College of Veterinary Medicine at North Carolina State University. “Rehydrating those calves is critical,” he says.

That means supportive treatment with fluid and electrolytes is vital, regardless of the cause of scours—whether bacterial, viral, protozoal or something else, says George Barrington, professor of large-animal medicine at the Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine.

And often, those life-saving fluids can be given orally, says Derek Foster, professor of ruminant medicine, North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine. “My rule of thumb is that as long as the calf can get up and stand and still has a suckle reflex, we can give oral fluids, and the calf doesn’t need IVs,” he says.

Check first

If you know how dehydrated the calf is, you’ll know if you can turn things around with oral fluids. “When a calf gets about 5% dehydrated, we notice clinical signs,” Barrington says. The calf is dull — not as strong and perky — and may not run off as fast when you approach.

“If you pinch the upper eyelid or the neck or wherever the skin is thin and can be pinched [skin tenting], and see how fast it sinks back into place, this gives a clue. If the calf is less than 5% dehydrated, it goes back into place quickly. At 5% or more, the skin stays tented a few seconds. The more dehydrated the calf, the longer the skin stays tented,” he says.

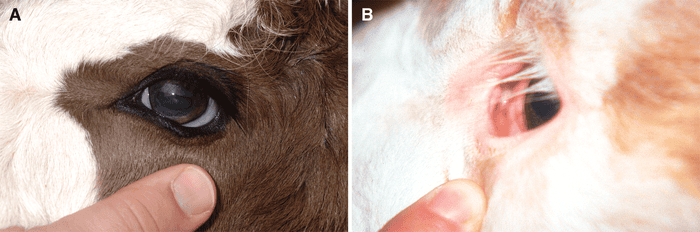

A calf will show clinical signs of dehydration with only a 5% loss of fluids. Photo A shows a healthy calf. One way to tell if a calf is critically dehydrated is to look at the eyes. The more sunken the eyes (photo B), the more dehydrated the calf is.

In a normal calf, the mouth is moist. “If that moisture becomes tacky or sticky, the calf is about 6% to 8% dehydrated. If it feels really dry, the calf is severely dehydrated. Also, in the dehydrated calf, the eyeball looks like it is sinking back into the head,” says Barrington. That’s because tissues around the eye are dehydrated.

“The more sunken the eyes look, the more dehydrated the calf is,” says Smith. “If the eye is right there under the eyelid, hydration is fairly normal. If you roll down the lower lid and see a big space there, this indicates dehydration,” he says.

“By about 12% dehydration, you could lose the calf. There’s a small window between 5% [when you can tell it’s actually dehydrated], to 10% or 12%, when he’s on death’s doorstep,” says Barrington. You want to intervene well ahead of that point, while the calf is still strong and can turn around more quickly.

Oral or IV fluids?

Ideally, you want to give fluids orally — while the calf still has a functional gut. When it gets severely dehydrated, fluids just sit in the stomach and can’t be absorbed because the GI tract has shut down. If the calf can still stand and walk — even if it’s slightly weak and wobbly — it may not need IV fluids.

“If the calf is down, however, and can’t get up without assistance, he may be too far past the point for oral fluids. Muscles become flaccid and weak, ears and inside of the mouth will be cold, body temperature low, and the mouth dry. If he gets so dehydrated he becomes shocky, he needs intravenous fluids as soon as possible,” says Barrington.

Cold extremities (poor blood circulation to legs and feet) usually mean the calf is in shock. If it has a bacterial infection and sepsis, with bacteria or their toxins getting into the bloodstream, resultant damage may put the calf into shock. Blood circulation is compromised and shunted to the vital internal organs, and is not being sent to the nonessential extremities or peripheral tissues. That’s why skin and legs will be cold. “Shock may accompany dehydration, but not always,” says Smith.

Knowing when a calf is past that window when you can give oral fluids is crucial: to be able to give IV fluids before it goes downhill too far in shock. “Many producers can put in an IV; but if someone doesn’t know how and wants to learn, their veterinarian can show them how, or walk them through it over the phone,” says Barrington.

How much fluid?

If the calf is still in the window where you can treat with oral fluids, you need to know how much to give. “Based on the calf’s weight, we consider three things. First is what the calf needs for normal maintenance [how much it would normally drink in a day]. Second is the degree of deficit from dehydration. Third, how much is he continuing to lose via diarrhea?” says Barrington.

“Sometimes people are surprised by the volume needed. If the calf is 5% or more dehydrated, you can estimate the amount of fluid needed by estimating how much the calf weighs. A gallon of water weighs 8 pounds,” he says.

If a calf has been off feed (not nursing) and scouring, it may be very dehydrated. “For example, a 150-pound calf would typically need about 4 quarts of fluid per day just for maintenance, and will likely drink nearly twice that much milk. If he’s dehydrated just 5%, he’s down about that much already — and will need about twice that much in a 24-hour period just to get back to a good level. A 150-pound calf that’s 5% dehydrated is already about 4 quarts in the hole to begin with,” Barrington says.

“During a 24-hour period, this calf would need about 8 quarts to satisfy his deficit and maintenance, plus what he’s continuing to lose via diarrhea. He might need 10 or more quarts of fluid in a day, split into three feedings. One feeding might help, but it’s not enough,” says Barrington.

Also, the younger the calf, the more quickly it will dehydrate with scours. A small young calf has no body reserves; it’s more urgent to give fluids often. If a very young calf gets severe diarrhea (or older calves get severe gut infections), sometimes the only way you can turn it around is to give fluids every six to eight hours, and sometimes even more frequently, depending on the situation.

It’s important to keep administering electrolyte fluid until the calf is no longer scouring. “A lot of producers ask about this,” says Smith. “If they give electrolytes and the calf goes back to the cow, should they give electrolytes again? Calves often have diarrhea for several days. As long as you can catch them, they probably need to be kept on fluid and electrolytes to make sure they don’t relapse,” he says.

What to give

It’s important to use a good electrolyte solution. “Many stockmen think one product is as good as another, but this is not the case,” says Smith. “When comparing electrolyte products in terms of rehydration potential, the sodium content is important. Water by itself will not rehydrate the body. This is why athletes don’t just drink plain water; they drink Gatorade. Make sure the sodium concentration of the oral electrolytes you choose is adequate,” he explains.

Barrington says it’s easier to buy a commercial product than try to mix the ingredients you’d need for reversing electrolyte imbalances. “It must contain salt [sodium and chloride], potassium, an energy source like glucose, and amino acids like glycine or alanine. The glucose and amino acids aid in absorption of electrolytes [especially the sodium, which in turn helps the gut absorb fluids]. Oral electrolyte solutions typically have sodium, chloride and potassium [the actual electrolytes] plus an energy source to aid sodium absorption, as well as provide a little energy for the weak calf,” he explains.

“Since most of these calves are acidotic [due to dehydration causing electrolyte imbalance], commercial electrolytes may also contain some kind of buffer. There are several different ones, including bicarbonate, acetate, citrate, etc. All of them have various advantages, depending on the calf’s situation,” he says. Ask your veterinarian which products might be best for certain cases.

Smith Thomas is a rancher who writes from Salmon, Idaho.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like