USDA Economic Research Service data show pasture and rangeland shifted to smaller operations.

April 5, 2018

by James M. MacDonald and Robert A. Hoppe

The trend has been dramatic and unstoppable, at least for cropland. Indeed, the mantra for farms has been to get big or get out. But for cattle operations, the trend has been the opposite, according to research from USDA’s Economic Research Service.

Beef cowherds, and the calves that they birth, typically graze on pasture and rangeland, which showed no consolidation in the research period. Other livestock, such as sheep, goats, and horses, may also graze on pasture and range—but cattle are the major users of what amounts to nearly half of all U.S. farmland. Hence, cattle grazing, and the pasture and range that they graze on, are an important exception to the strong trend toward consolidation in agriculture.

Pasture and rangeland accounted for 45% of all U.S. farmland in 2012, while cropland accounted for 43%. While cropland consolidated into larger farms between 1987 and 2012, pasture and rangeland did not, but instead shifted away from the largest farms and ranches and toward smaller operations.

In 1987, farms and ranches with at least 10,000 acres of pasture and rangeland operated more than half (51%) of all pasture and rangeland, while those with less than 1,000 acres held 15%. By 2012, the share operated by the largest acreage class had fallen to 44%, while farms and ranches with less than 1,000 acres of pasture and rangeland operated 22%.

U.S. farmland shows very little consolidation since the 1980s. However, that seeming stability reflects two diverging underlying trends: considerable consolidation in cropland and in crop and livestock production, set against shifts of pasture and rangeland toward smaller operations.

Consolidation in livestock varies

Consolidation in livestock production follows a different pattern than that in crops. When it has occurred, it has not unfolded at a steady and persistent rate over time. Instead, livestock consolidation proceeded with periods of sharp change in the size of operations, followed by stability.

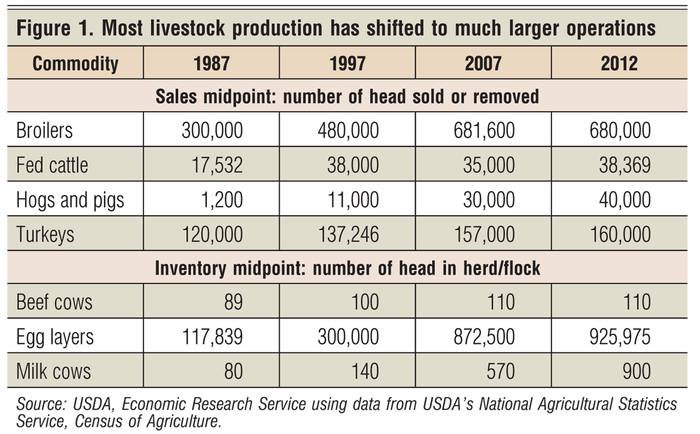

As in its analysis of specific crops, ERS researchers tracked midpoints for each livestock commodity across census years. Researchers used a sales midpoint—based on the number of animals sold or removed during a year—for livestock feeding industries like broilers, turkeys, and fed cattle. Researchers used midpoint herd or flock inventory values for egg layers and cows (Figure 1).

Some shifts have been dramatic. For example, the midpoint milk cow herd in 1987 was at 80 cows—half of U.S. milk cows were in herds of at least 80 cows, and half were in herds with no more than 80. By 2012, the midpoint had increased more than tenfold, to 900 cows. Similar dramatic increases occurred in egg layers and in hogs and pigs, as each industry underwent striking changes in organization and farm size.

In other sectors, like broilers, turkeys, and fed cattle, production shifted to larger operations by 2012, but the shifts were not persistent, and there is little evidence of continuing consolidation in 2007-12. Major reorganizations of those industries occurred earlier, in the 1960s and 1970s, and the later shifts reflected further adjustments.

One important sector shows little consolidation. The midpoint beef cow herd was at 89 cows in 1987, a bit larger than the midpoint milk cow herd. By 2012, the midpoint beef herd had increased, but only modestly, to 110 cows.

MacDonald is chief of the ERS Structure, Technology and Productivity branch and Hoppe is an agricultural economist with the Resource and Rural Economic Division, Structure and Productivity Branch.

You May Also Like