Controlling grasshoppers and Mormon crickets takes a watchful and considered approach.

April 6, 2015

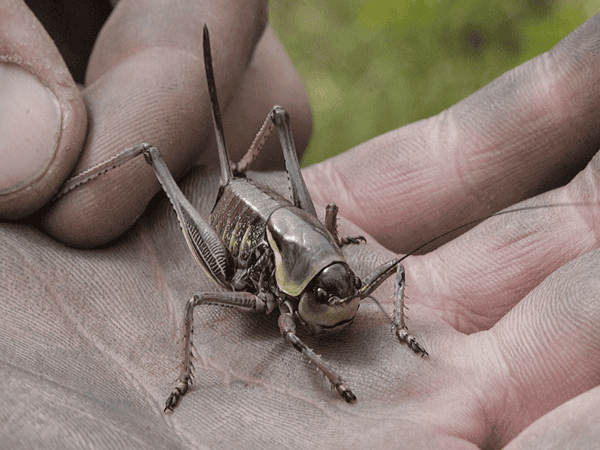

Nearly 400 species of grasshoppers are native to the 17 Western states. Mormon crickets are closely related insects that are also highly mobile and capable of migrating long distances. In large numbers, these insects can devour nearly all forage plants in their path.

Grasshoppers can be a problem anywhere, but their damage is most noticed in dry climates where vegetation is sparser than in humid environments. It’s when forage is in short supply that ranchers can ill afford to have grasshoppers eating feed their cattle need, says Charles Brown, policy manager for USDA’s Rangeland Grasshopper and Mormon Cricket Suppression Program.

Mormon crickets are closely related to grasshoppers. Highly mobile, they can migrate long distances.

Suppression efforts are aimed at the bad years, Brown says. “We try to predict when outbreaks will occur, but it’s difficult. Weather makes a difference, especially when grasshoppers and crickets are hatching. A cold snap, or a lot of rain during the hatch, can substantially reduce what would have been an outbreak population,” he says.

Of the hundreds of grasshopper species in the West, only about a dozen that feed on grasses have the capacity to reach high population numbers quickly and then move to other areas. Once the species, and its numbers, are determined, decisions on suppression can be made, Brown says.

“When populations are several times what they normally would be, and it’s a species capable of competing with livestock and moving to other areas, we give advice regarding treatments,” Brown says.

3 treatment options

Brown says his federal program uses three different insect treatments, but the one most commonly used is an insect growth regulator called Dimilin (diflubenzuron). The product affects the external skeleton, which inhibits young insects’ growth, and they die. “It must be applied early in the season, when grasshoppers/crickets are still growing. It doesn’t have any effect on adults, so timing is crucial,” Brown says.

Paul Blom, an Oregon Department of Agriculture entomologist, says that while Dimilin’s treatment window is much shorter than that of the insecticides, it doesn’t adversely affect as many nontargeted species.

“It also has a longer residual action [almost three weeks] and can give 80% to 85% effective control if applied when grasshoppers/crickets are very young,” he says.

Other treatments available are the insecticides malathion and carbaryl. Brown says carbaryl is very effective as a solid bait pellet, especially against Mormon crickets. “The bait is spread where they are or where they’re headed. The pellets are about the size of rabbit feed. If Mormon crickets are the vast majority of insects in the area, they reach the bait first — before nontargeted insects find it — and completely consume the pellets,” he says.

Application can be done either aerially or with ground equipment, such as an ATV; the choice depends on the terrain and individual situation, Brown says. “We typically use an approach called reduced agent-area treatments [RAATs], or skip swathing. We spray a swath, skip a swath, treating every other swath. This reduces the amount of insecticide used, and is effective because grasshoppers and crickets move. If they’re in one of the untreated swaths, they eventually move into one of the treated areas,” he adds. This method is also less harmful to other insects.

Application can be done either aerially or with ground equipment, such as an ATV; the choice depends on the terrain and individual situation, Brown says. “We typically use an approach called reduced agent-area treatments [RAATs], or skip swathing. We spray a swath, skip a swath, treating every other swath. This reduces the amount of insecticide used, and is effective because grasshoppers and crickets move. If they’re in one of the untreated swaths, they eventually move into one of the treated areas,” he adds. This method is also less harmful to other insects.

This practice has been used for many years with insecticides to control Mormon crickets. In recent years, Dimilin has also been applied in this manner, Blom says. It is effective longer, and young insects encounter it as they migrate over the landscape to forage. The earlier the treatment is applied, especially with Dimilin, the better the results.

“This is a suppression program. We’re not trying to eradicate grasshoppers or crickets, but simply control them. These native species are part of the ecosystem and provide food for birds and other animals. We try to reduce an outbreak to levels of a normal year, about 90% to 95% control. We never aim for 100%,” Blom says. The rationale is that, with fewer eggs laid, the effect will last for that season and a year or two after.

“Not every outbreak needs to be suppressed; many years, there might be enough forage for both insects and cattle,” Brown adds. In drought years, however, it may be tough for cattle producers when the insects consume most of the forage that is available. Mormon crickets are notorious for eating everything in their path, and undergo cycles that greatly impact ranchers and farmers.

Brown says treatments through his program must be requested by the landowner or land manager. “On federal land, the federal government pays 100% of the treatment cost; on state land, it’s 50%; and 33% on private land,” Brown says.

70+ photos showcasing all types of cattle nutrition

Readers share their favorite photos of cattle grazing or steers bellied up to the feedbunk. See reader favorite nutrition photos here.

Blom adds that federal assistance carries extra detail, paperwork and regulations. “The process the federal government is required to follow takes a fairly long time; whereas, the private individual or cooperative can quickly implement suppression,” Blom says. “Private owners usually feel the extra complications required for support from the federal government aren’t worthwhile.”

And that’s important consideration, because a delay in initiating treatment can allow the grasshoppers to mature, he says. Wait too long, and the target insects aren’t as susceptible to the optimal tactics, or they’ve migrated to another area.

Cooperative efforts

Bruce Shambaugh is the national operations manager for grasshopper and Mormon cricket control. He’s also Wyoming’s state plant health director for USDA’s Plant Protection and Quarantine unit. He oversees all the PPQ programs, including grasshoppers, in Wyoming and manages field operations for the entire grasshopper-Mormon cricket program in 17 Western states.

“My job is to try for consistency in how we do our field operations. There are differences from state to state because of differences in the land where these insects occur and other people involved. Each state has evolved its own program, and I try to make these as consistent as possible, while still allowing the flexibility they need to do what they need to do,” he says.

The program’s authority stems from the Plant Protection Act, which covers 17 Western states with a high majority of rangeland. The program includes population surveys of insects in order to better predict and target control efforts.

That data goes on a map to aid in predicting areas of interest the following spring. “We provide this information to all cooperators, stakeholders, land managers, Fish and Game, and landowners, so we can work together to manage the program for grasshoppers and Mormon crickets. We try to involve everyone, since we all have a common goal to maintain a healthy rangeland ecosystem,” he says.

Any information received through meetings with landowners or cooperators during the year is helpful, he adds, but the surveys often are limited to are‑as with public access.

“In the adult survey, we use a 5- to 10-mile grid. In areas where there are large stretches of private land, or even public land with limited county road access, we might miss a lot; so we rely heavily on landowners to let us know of potential problems. They can call us, or a county weed and pest district, Extension service, or local land manager,” Shambaugh says.

He says most people don’t notice young hoppers early in the year because they’re less than a quarter-inch long. “One of our challenges is to get landowners looking for young insects early in the spring. A person often has to get out and walk, or get down on hands and knees, to look closely at the grass — to notice whether there are 1 or 2 insects hopping, or 10 or 20,” he says.

“If the rancher contacts the state plant health director with USDA, we can do a survey. At the request of a private landowner, we’ll go wherever they want, but we don’t go across public land unless we have permission.”

Bruce Schambaugh

Identifying a high population quickly enough to make effective management decisions is the challenge, he adds.

“This is why the adult surveys in late summer are important; they help us identify what might be — or might lead to — potential problems the next year or two. If we can do some planning and get interested landowners coming to meetings that winter, we can do an effective job on suppression treatments the next spring,” he explains.

Shambaugh says collaboration is the key to the program’s success. “We need landowners to be an active part. I recommend that landowners keep their eyes open for young hoppers. Write down or take a photo of what you see, and then report to your state plant health director, state ag department or local Extension agent.”

Shambaugh stresses that grasshoppers and Mormon crickets are so mobile that regional management can be a challenge. To be effective, cooperation is a must. “Otherwise, you might still have a hopper problem after spending money for control on your own property,” he says.

Heather Smith Thomas is a rancher and freelance writer based in Salmon, Idaho.

You might also like:

60 stunning photos that showcase ranch work ethics

When should you call the vet on a difficult calving?

What's the value of a bred beef heifer in 2015?

Meet the nation's biggest seedstock operators

What you need to know about cattle ingesting net wrap

Prevention and treatment of cow prolapse

You May Also Like