Keeping the brush invasion under control is a lifetime endeavor.

October 31, 2017

It’s a fight he’ll likely never win. But with an extensive prescribed burn, herbicide and grubbing program, Andrew Bivins hopes to eventually mimic Mother Nature in minimizing forage loss caused by the pasture predators of brush and weeds.

Those are the tactics in Bivins’ battle with water-robbing woody plants like juniper and mesquite. And while he still has a long way to go, he’s pleased with the outcome so far.

Bivins is part of a long-standing Texas Panhandle ranching family. He runs the historic JA Ranch about an hour southeast of Amarillo. One of the first ranches in the area, James Adair and famous cattle baron Charles Goodnight established the JA in the 1870s. In addition, Bivins’ family continues to operate the XL Ranch outside of Amarillo, as it has for over a century.

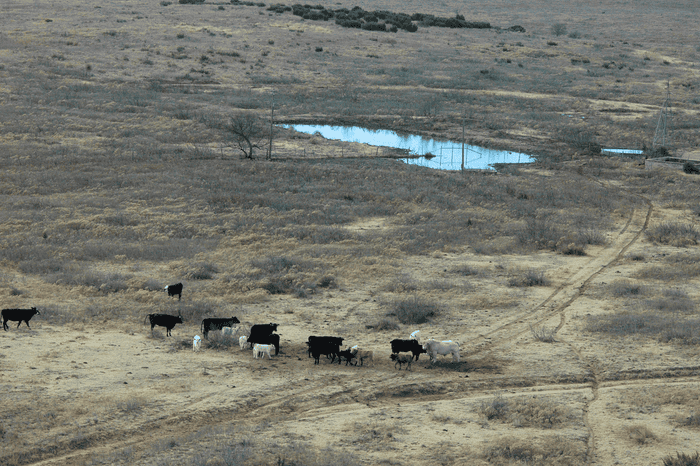

Much of the JA lies in Palo Duro Canyon, where the terrain is rough and rocky, and grass is a premium. The ranch averages 18 to 20 inches of annual rainfall. It relies on native grasses, mainly side-oats grama, buffalograss and little bluestem.

Since grass can be scarce, virtual forests of juniper and widespread mesquite and prickly pear cactus are more than a menace. “Brush control helps us open up more grazable acreage and reduces gathering costs,” Bivins says.

Bivins works with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Texas A&M University AgriLife Extension to identify methods of controlling woody plants and cactus. He also consults with herbicide company reps to develop prescription spray programs.

“In early years, natural prairie fire would normally set back about 10% of encroaching woody species,” Bivins says. “Our red berry juniper was much less prevalent 100 years ago. However, when ranchers and others began working to suppress wildfires, the juniper spread deeper into grassy areas.

“Now, we’re attempting to do what nature once did through prescribed burns. We try to idle 10% to 15% of the ranch a year to mimic the fire cycle the region evolved under.”

Rebuying the ranch

Simply grubbing the land won’t work. “If you cut red berry juniper at ground level, it’ll grow back because you haven’t hurt the bud zone, which is belowground,” he says. “Fire, along with grubbing, helps set back the juniper problem seven to 10 years.”

What’s more, juniper grubbing is extremely cost-prohibitive. “It costs $400 to $450 per acre. You’re basically rebuying the ranch.” Following grubbing, a cost-efficient prescribed fire costs $10 to $12 per acre to clean up re-sprouts and dead trees on the ground.

Brush management has opened significantly more grazing for the Angus-Charolais-cross cattle on the JA Ranch. With better grazing come higher stocking rates; costs and returns must be considered, though, to ensure brush control adds to the bottom line.

For mesquite that isn’t within a juniper area, Bivins relies on herbicides. “An aerial application will usually control mesquite,” he says. “Cost is about $30 per acre. Native virgin mesquite responds well to chemical. However, follow-up chemical treatments have not been near as effective in controlling the trees.”If a pasture has a mesquite-juniper mix, “we will typically just burn it,” he adds. “I’d be happy with having a mesquite monoculture problem over the red berry juniper.”

Prescribed burning is usually done between January and March, when grass is dormant. With the Texas Panhandle region’s reputation for strong winds, Bivins monitors weather forecasts for mild days and 23% to 35% humidity.

“Fire is a very valuable tool when done correctly,” he says. “If folks don’t respect fire, they will end up losing [control of] it — and possibly cause loss of property or even loss of life.” That’s why safety of fire and property managers, livestock and wildlife is the main concern.

The burn, along with herbicides, also helps manage prickly pear. “We have a window for spraying prickly pear,” Bivins says. “When prickly pear are growing, they develop new pads about the size of silver dollars. After the late-winter fire, we can obtain good coverage using about 75% less herbicide as to when plants are in full bloom.”

Long-term weather can also impact the effectiveness of a prescribed burn, says Tim Steffens, professor of rangeland resource management at West Texas A&M University in Canyon, and Extension rangeland specialist for Texas A&M AgriLife.

“In the long run, different plant species react differently to wet and dry conditions,” he says. “For example, if a dry winter is forecast, a full burn will desiccate prickly pear and kill it in one winter. But if it turns out wet, prickly pear will see regrowth.”

Herbicide management

Steffens says producers must decide which pasture management program can best handle their problem. For herbicide selection, Steffens relies on AgriLife and other Extension research findings.

“My bible is the ERM 1466 publication on chemical weed and brush control,” he says. “It’s updated regularly on the correct usage and application of various herbicides on specific weeds.”

The trick is assuring herbicides are used correctly on the correct plant. Some producers see one weed and immediately spray. Others have never used a herbicide in their lives.

“The first may be spending more money than will be paid back from increased production, and the latter may be losing productivity that could be improved with a timely herbicide application. Alternatively, maybe management in the first case is causing the weed problems; and in the latter, he is avoiding them and doesn’t need to control the weeds.”

“If a producer uses a herbicide and the problem keeps coming back, he may be putting on Band-Aids and could end up with nothing but a big ball of Band-Aids — and the situation is probably getting worse.”

If a ranch depends on wildlife management and hunting as a profit center, precautions may be needed before using herbicides. “Plants may be good for quail, deer or other wildlife, but not for livestock,” Steffens says. “That requires producers to be more surgical in making herbicide applications. Kill what you want to kill, without hurting wildlife and soil stability.”

Drought breeds weeds

After a severe drought like in 2012 in the Midwest and 2011-13 in much of the Southwest, prudent herbicide management is even more important.

“Once rain finally returns, there can be big flushes of weeds,” Steffens says. “But they’re likely annual weeds and will often go away, especially if they’re native. Native grass will likely come in behind them without the expense of killing the weeds. If we manage to favor the grass, herbicide may not be needed.

“Look at managing what you want and worrying less about what you don’t want,” he says. “Think of the soil as the earth’s skin. Bare ground is a wound and the weeds are a scab. You need to worry about healing the wound, not removing the scab before the wound is healed.”

You can predict some problems, he adds. “Parts of the High Plains see annual broomweed. If it’s a dry summer, but a wet fall and winter, we may see annual broomweed in the spring. We can plan to control it early on. If our grazing during the drought increases the amount of bare ground, we can expect a bigger problem that is harder to control.

Draws on the JA Ranch usually are not burned or grubbed to benefit wildlife, help control erosion and capture more runoff.

“Many of these plants can be short-term, high-quality feed, and can be an asset if managed right. We’ve learned that if we have sunflower, 4-inch-tall plants are very palatable to cattle, but 12 inches tall are not. Even small Russian thistle plants can provide a free forage source in the early spring.”What’s more, herbicide application may control weeds but may also increase palatability of poisonous plants that are then more likely to be consumed by livestock. Steffens says herbicide-treated areas with poisonous plants present should not be grazed until the toxic plants dry up and lose their palatability.

Bivins says weed and brush control can be just as important to a ranch’s bottom line as selecting the right feed supplement.

“You will always have brush management costs,” he says. “It’s a line item just like your feed bill. You know you’re going to have to have it, so you need to budget for it.”

Stalcup writes from Amarillo, Texas.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like