Use livestock to create firebreaks

Livestock can be the best fire prevention tool around for vast expanses of rangeland.

Frequency and severity of wildfires in the West and in the Southern Plains suggest every grazing manager should consider developing firebreaks prior to fire season. While there are a number of ways to create a fire break, it’s a task that may be best done with controlled grazing of livestock.

In the 11 westernmost states, cheatgrass is wreaking havoc on native plant communities unsuited to frequent fire. Every firestorm reduces native plants and gives the cheatgrass more chance to create more firestorms that will further expand its range. Typically these occur in summer, after the cheatgrass has set seed and dried.

In the southern half of the Great Plains, which is dominated by warm-season grasses and forbs, the early spring is a virtual tinderbox as dry forage plants and a growing load of shrubs and cedars stand ready to ignite. High winds and low humidity dominate the region, and though some years are worse than others, most years offer at least some dry, windy days that can push wildfire through the landscape and potentially burn tens or hundreds of thousands of acres.

In either situation, controlled grazing of livestock along naturally existing firebreaks such as roads may be the cheapest and best method to help combat these fires. Besides a probable cost advantage, livestock offer another advantage over mowing, which leaves the fuel on the ground.

Livestock actually consume the forage, says Scott Cotton, area Extension educator for the University of Wyoming and a former wildfire firefighter. Cotton has also lived and worked in Montana, Colorado and Nebraska.

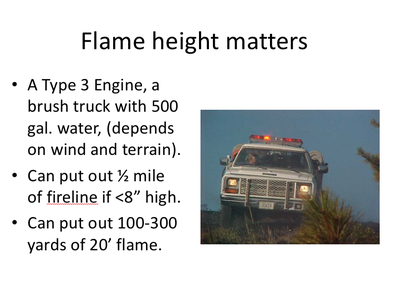

Cotton says people who haven't faced serious range fires tend to underestimate their danger. Rangeland fires normally have the fewest responders, move much faster and cause more deaths than would a forest fire under comparable conditions.

Cotton and others in the West recommend grazing managers consider dominant spring wind direction and then plan fire breaks along roads on that windward edge of the property, grazing the forage short enough to significantly shorten and slow the flames and give firefighters a chance to stop the fire. Flame height and speed of travel are directly affected by how much fuel is available, assuming the same relative humidity, temperature and wind speed.

An Idaho publication explains this phenomenon in sagebrush ecosystems under less extreme environmental conditions. In the absence of sagebrush cover, if fine fuel loading is less than 627 to 728 pounds per acre, fires will sustain only under environmental conditions characterized by less than 15% relative humidity, temperatures exceeding 84.2 degrees F, dead fuel moisture less than 12%, and wind speeds greater than 9.9 miles per hour. When fine fuel loading is above 1,904 pounds per acre, fire will spread under a wide array of environmental conditions.

These conditions would be at least similar in similar ecosystems and under similar conditions in the Southern Plains in the spring.

"Under extreme conditions, characterized by low fuel moisture and relative humidity, and high temperature and wind speed, wildland fires are driven more by weather conditions than by fuel characteristics. Therefore, as fire weather conditions become extreme, the potential role of grazing on fire behavior decreases and may become meaningless," those authors warn.

Nonetheless, the majority of fires are not of this worst type.

Cotton says once you have chosen the area to graze down a firebreak, you should set up an electric fence 200-300 feet wide along the road and put the livestock into it.

“Based on your ecosystem and grass species, the timing of grazing will vary,” he says.

In cheatgrass country, it's possible to graze the plants while in a relatively high-quality state. In dormant, warm-season grass country, you would ideally want to graze it down in winter with animals in a lower state of nutritional requirements or you might graze it heavily and use protein supplement to attain reasonable performance.

Cotton also says you might ideally want to include multiple species of livestock, depending on the types of plants present in your firebreak. Cattle are going to concentrate more on grass and some forbs, while sheep and goats will eat more forbs and shrubs.

He says once the firebreak is ready, you should notify your neighbors and your fire department about its presence.

Although this is not necessarily new technology, it remains generally poorly used.

Cotton adds, "Targeted grazing trials by Texas A&M and Utah State University reduced grass and brush, including mesquite, to create fire breaks in the late 1990s. Research on using livestock to control fire risks have been underway since 1927 at land grant universities. Zimmerman and Neuenschwander wrote one of the most significant papers on the subject in 1984, which was published in the Journal of Range Management."

Cotton adds, "Targeted grazing trials by Texas A&M and Utah State University reduced grass and brush, including mesquite, to create fire breaks in the late 1990s. Research on using livestock to control fire risks have been underway since 1927 at land grant universities. Zimmerman and Neuenschwander wrote one of the most significant papers on the subject in 1984, which was published in the Journal of Range Management."

In a 2002 book from the University of Nevada Press, "Cattle in the Cold Desert," the authors concluded properly applied livestock grazing, which has been removed or over-controlled across many public lands, is exactly the prescription to help decrease cheatgrass-based fire problems.

The idea is slowly drawing attention in the far West, with the Bureau of Land Management experimenting with the idea on a few of the millions of acres it manages. Perhaps the same technology can help with fire problems in the middle of the nation, as well.

Newport is editor of Beef Producer and BEEF Vet, sister publications to BEEF.

Pumper truck vs flames graphic courtesy Scott Cotton, U of WY

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)