Cattle Disease

thumbnail

Livestock Management

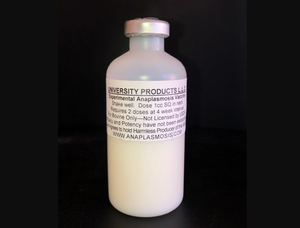

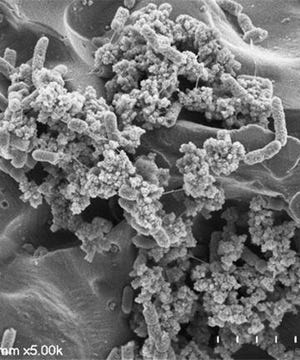

Producers on alert for emerging cattle disease in MissouriProducers on alert for emerging cattle disease in Missouri

Main route of transmission is through the Asian longhorned tick, an invasive species found in 19 states.

Subscribe to Our Newsletters

BEEF Magazine is the source for beef production, management and market news.

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)