No matter the water source — dugout, pond, tank or automatic waterer — quality and quantity are crucial.

March 2, 2023

The most important task before rotating pastures, or turning livestock out in the spring, is to properly test the water sources available. Miranda Meehan, North Dakota State University Extension livestock stewardship specialist, says that water quality should be ensured before turnout — not just in the spring.

“We recommend monitoring water sources and testing before we put animals in, as water quality is going to fluctuate throughout the growing season,” Meehan explains. Low-quality water can reduce animal health and productivity, while high-quality water can increase water intake and improve production.

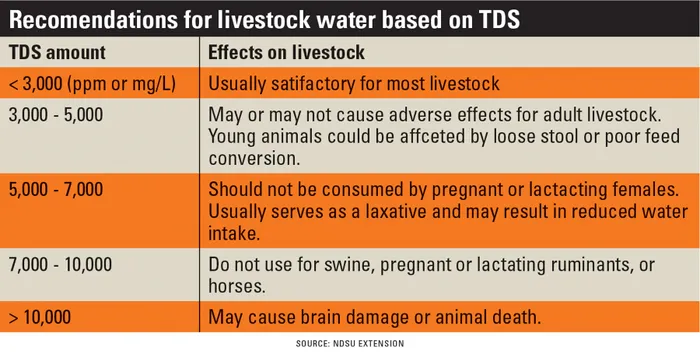

Producers should check water sources for both total dissolved solids and levels of sulfates, pH and nitrates. Meehan says that the salts in surface water become more concentrated as water levels decline and can reach levels that are toxic to livestock.

“Testing with a hand-held TDS meter is one of the quickest ways to know what’s in your water, and we recommend sulfate and nitrate test strips as well,” she says.

Sulfur and nitrates

The cumulative levels of sulfur and nitrates from both livestock water and diets could cause toxic levels to build up in animals. Meehan says that while the Dakotas have seen more issue with sulfates over nitrates, levels of both should be evaluated.

“Moving south into Nebraska, we’ve seen larger issues with the nitrates, and we need to make sure to test food too,” she says.

While some animals might avoid high-saline water sources, some might still consume this water.

“Especially during drought, we see this issue of salts becoming more concentrated as the water evaporates,” she says.

While livestock can have differing tolerance to salt content depending on age, species and condition, the clinical signs of salt poisoning include weakness, dehydration, tremors, wandering, partial paralysis and death.

For water sources that are tested with too high of TDS, sulfate or nitrate levels, producers have two main options. Block off the water source and provide a supplemental option or dilute the existing water source.

“It’s almost just easier to exclude these water sources or move to a different pasture, when possible, because diluting to the right levels might be a bigger challenge,” Meehan says.

Water while rotating

For producers rotational- or management-intensive grazing through a series of paddocks, there are multiple ways to get clear, cool water to cattle.

“Planning out the water source is critical because it is going to impact grazing distribution” when you are rotating through paddocks, Nebraska Extension educator Ben Beckman says. “If dugout watering holes dry out, cattle might leave an entire side of a pasture underutilized. Last summer, if a dugout was your only water source, you probably weren’t able to use that pasture.”

As for water quality, cattle are very forgiving, Beckman says — especially dry cows, open cows or those animals that aren’t growing. But for pregnant and lactating cows, growing calves and feedlot cattle, the highest water quality is crucial.

“Water impacts feed intake, gain, health and well-being,” Beckman explains. “A rule of thumb is if you look at the tank and the water doesn’t at least look good enough to drink yourself — is covered over with moss or scum — it probably isn’t good enough for your cattle,” he says. But getting water that is not too hot and is clear to grazing cattle takes planning and thinking.

Many rotational grazing systems have water lines networking across the system of cross-fences, with hydrants or quick water connections to portable tanks that are moved with the cattle through the paddocks.

Capacity

“Make sure you have enough capacity for summer grazing,” Beckman says. This means having a large enough tank or multiple tanks to water the entire herd, if they all come to water at once, or having smaller tanks but an extremely high flow rate so the tanks fill very rapidly.

Some producers refill water tanks with a large nurse tank as the cattle are moved. No matter the system, the capacity is the key. “That’s why the typical old windmill had two or three large tanks around it, because if there was no wind, there was enough water capacity to still water the herd,” Beckman says.

Even cattle on winter grazing pasture or cornstalks need water. “Cows are OK for a few days in the winter, because they can get enough water from the snow,” he says. “But this puts a stress on the animals because they have to melt the snow, and this lowers their internal temperature, increases their energy requirements and impacts their feed intake.”

The rule of thumb for quantity of water in the winter is 1 gallon of water for every 100 pounds of body weight. This jumps up to at least 2 gallons per 100 pounds for lactating animals in the summer.

While no one has a crystal ball to predict whether drought will continue in 2023, Meehan explains that both quality and quantity should be closely monitored. “Continue to monitor not just the quality, but ensure adequate supply, and have a plan in place for an alternate water source for pastures,” she says.

You May Also Like