Track when calves are born to determine beef cow herd productivity.

February 16, 2021

A little record keeping upfront when calves are born can determine the productivity of a cattle herd.

According to University of Missouri Extension veterinary Craig Payne, evaluating a calving distribution provides insight into the reproductive performance of a cattle producer’s herd.

Payne completed a three-year project that tracked calving dates and found early-born calves had heavier weaning weights, along with the ability to put on more pounds.

Need for documentation

Calving distribution is often expressed as the percentage of calves born at 21-day intervals, since 21 days is the average length of the estrous cycle in cattle.

Payne tracks calving distributions as part of a three-year project to help beef producers improve whole-herd record keeping. This is important for two reasons, he says.

First, dams of early-born calves have more time to recover before the next breeding season. They will likely be cycling at the beginning of the breeding season and have a better chance of becoming pregnant.

Second, early-born calves have longer to gain weight. This gives the owner more pounds of calf to sell and bigger profits at marketing time.

Payne says weaning weights collected from a northwestern Missouri operation in fall 2020 show that steer calves born in the first 21 days of the calving season averaged 47 pounds heavier at weaning than calves born during days 22 to 42 (537 pounds vs. 490 pounds).

While the number of calves in this group is relatively small (47 steers born in the first 21 days, and 12 born during days 22 to 42), Payne says other studies report similar weight differences.

How to track delivery

Begin tracking calving distribution by establishing the date of the initial counting period. One option is to start the first period 283 days from bull turn-in or artificial insemination.

If this information is not available, begin the first 21-day period when the third calf is born. Both methods work, Payne says, but use the same method to be consistent.

Once you have the start date, count the number of calves born in the first 21 days of the calving season and divide that number by the total number of calves born, Payne says.

Repeat the process for days 22 to 42, days 43 to 63 and after day 63. Count all full-term calves born, dead or alive. Also, include calves born before the beginning of the first 21-day period.

Finally, evaluate the calving distribution of first-calf heifers (2-year-old cows) separately from the mature herd. Their breeding season is often earlier or managed differently.

Compare your cattle

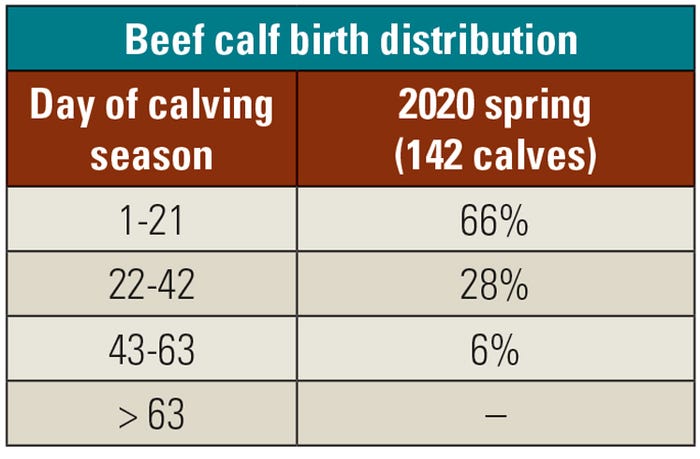

Once you know your herd’s distribution, compare it to the industry standard. Benchmarks for the first, second and third 21-day periods are 65%, 23% and 7%, respectively. The remaining 5% of calves are born later than 63 days.

The following is the calving distribution of 142 calves from a 2020 spring calving herd in northwestern Missouri:

Based on the calving distribution, this herd performed better than the industry standard.

To achieve the targets, all cows must cycle at the beginning of the breeding season, and bulls must be fertile.

“If your distribution is unfavorable, meaning a higher percentage of calves are born later in the calving season, it could indicate one or more problems and will require more investigation,” Payne says.

Factors to consider are nutrition, bull power or fertility, disease or conditions that cause early embryonic loss or infertility, or a mismatch between herd genetics and environment. Also, look at the calving distribution by age category, pasture and other groupings to see if a specific group is responsible for differences.

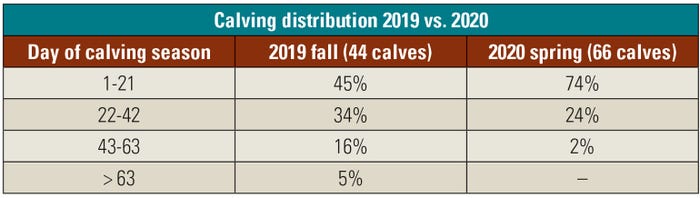

The following distributions are from two groups of cows owned and managed by the same beef producer:

Notice the 2019 fall calving herd had an unfavorable distribution, while the 2020 spring calving herd exceeded the benchmark. According to the producer, this difference can be explained by management intensity.

The spring herd is intensely managed for reproductive success. The fall herd, however, is a mixture of purchased cows of unknown origin, late-fall calving cows bought from another producer and cows carried over from the spring herd.

For more information on the record-keeping project, call Payne at 573-882-8236.

Source: University of Missouri Extension, which is solely responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like