Developing A Ranch Biosecurity Plan

Weaning time is a good time to think about biosecurity; developing a plan isn’t as difficult as it seems.

Consider the term “biosecurity” and what do you think of? People running around in hazmat suits conducting chemical warfare on some dreaded disease?

Consider the term “biosecurity” and what do you think of? People running around in hazmat suits conducting chemical warfare on some dreaded disease?

In its most extreme, that is biosecurity. The reality, however, is that implementing a biosecurity plan for your ranch isn’t difficult.

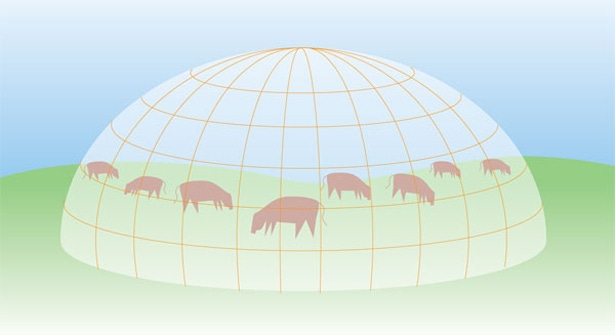

Biosecurity describes any management program designed to prevent or minimize disease, or prevent and control pathogens harmful to the health and welfare of your herd, says Bob Sager, veterinarian at the University of Missouri’s (MU) Clydesdale Teaching Hospital.

So, because you sat in on a Beef Quality Assurance (BQA) presentation and have a vaccination program, you’re biosecure, right? It’s a start, says Jeff Ondrak, beef cattle clinical veterinarian at the University of Nebraska’s Great Plains Veterinary Educational Center in Clay Center.

“BQA puts people into the thought process of looking at what can go wrong and taking steps to avoid that happening,” Ondrak says. “But, especially as it relates to preconditioning and weaning, think about what kind of diseases are important in your area, then make specific plans to prevent them.”

He suggests thinking about biosecurity in two ways – biosecurity and biocontainment. “Biosecurity is preventing the introduction of an infectious disease into an operation; biocontainment is preventing the spread of disease within the herd.”

The steps you take to accomplish each of those, however, are generally the same.

Biosecurity

Biosecurity – dealing with animals coming into your herd – begins with isolating the cattle. “At a minimum, all newly purchased animals should be held away from the herd for 30 days,” Sager says. This allows you to check their health and reduce insect-borne disease transfer from the new cattle.

However, he realizes that isolating new cattle on arrival isn’t always done. In fact, the National Animal Health Monitoring System reported in 2008 that in herds of 1-99 beef cows, 35% had added new animals within the previous 12 months, without utilizing a 30-day isolation of the new arrivals. Meanwhile, in herds of over 100 cows, 64% added new cattle during the previous 12 months, without isolating new cattle.

“Up to 10% of the purchases were in pregnant beef cows with no knowledge of animal health status,” Sager says. Almost 20% were bulls introduced to the herd.

“These purchases didn’t involve any measure of quarantine or any other biosecurity measures,” he explains. That’s disturbing, he adds, particularly if the purchase didn’t involve any knowledge of the herd of origin or animal health measures taken by the seller.

Then there are the neighbors. “A key step is to understand your neighbors’ animal health programs and how they compare with yours,” Sager says. Then you can develop measures with your veterinarian to deal with pressures from surrounding herds.

That philosophy of “know thy neighbor” also applies to newly purchased cattle. Sager spent 37 years in private practice before joining the MU faculty. He says it always surprised him that clients would invest hundreds of hours studying EPDs, and thousands of dollars buying bulls and replacement females, but almost no time reviewing the ranch-of-origin’s health program.

According to Ondrak, record-keeping is important. Keep track of where the cattle came from, where they went upon arrival at your place, and who had contact with them so you can track down and, more importantly, stop the spread of any disease that may have hitched a ride.

Biocontainment

Biocontainment – preventing the spread of disease within your herd – is equally important. And records are important here as well, so you know where animals have been on your operation and who’s been in contact with them.

Isolation can play a role. If you’re running different bunches of cattle on different places, and they haven’t been in contact with each other, bringing them together in the fall is essentially the same as merging two outside herds, Ondrak says. The infectious agents that one herd was exposed to could differ from those that challenged the other herd. So, if possible, isolate different bunches of cattle, or at least the calves after they’re weaned, so you can sort out any health challenges that might arise.

Isolate sick animals, he says, and test for what’s wrong. “If we do some testing to identify the infectious agent, we can use vaccinations to control some of those diseases,” Ondrak says.

And then, wash your hands. If you haul cattle for a neighbor, you probably think about washing out the truck or trailer. “But if you’re working with a sick calf, maybe you ought to wash your hands, and clean your boots and clothes,” he suggests, to prevent spreading the problem further.

Partnerships

Ondrak and Sager agree any biosecurity and biocontainment plan works better when your veterinarian is involved as a year-round herd health consultant. “Today, the need for an animal health expert with current knowledge of biosecurity is more important than ever,” Sager says. That’s because new challenges always crop up.

Like leukosis, which is a slow-acting virus that circulates in the blood or the lymph system and causes a lymphoma-like condition. Little is known about it, and research is underway to learn more. “I think it’s a smoldering coal that we recognize as more of a problem in cattle now than we did just a few years ago,” Sager says.

And finally, Ondrak says, look beyond the medicine bottle. “A lot of times, producers and veterinarians focus on the animal. We want to prepare the animal for weaning and certainly we want to improve their immunity and increase resistance to infection. And certainly vaccinations and dewormers are a part of that whole process.”

But there are several other things to consider, including a low-stress environment. “Reduce dust, reduce mud and, depending on the time of year, avoid extremes in temperatures,” Ondrak says.

“Then we need to think about the disease-causing agent. And that’s really where biocontainment and biosecurity come into play – trying to reduce the exposure by how we manage the animals. If we do a good job dealing with these components, we’ll have a fairly successful weaning,” he says.

10 biosecurity tips

Establish a personal connection with your herd health veterinarian.

Know neighbors’ programs and background of purchased animals to ensure they’re on similar biosecurity programs.

Quarantine all new animals at least 30 days.

Plan on only purchasing tested animals.

Understand how disease can be spread or introduced. Consider water sources, manure, vehicles, wildlife, feedstuffs, and non-livestock such as dogs, birds, insects and humans.

Understand that carrier animals can appear normal, so quarantine and test before purchase.

Understand specific diseases can be transmitted by vaccination needles, such as anaplasmosis and bovine leukosis.

Vaccinations aren’t 100% effective, but biosecurity is both cost-effective and the least costly control program for minimizing disease.

Customize a biosecurity program to your operation’s needs and concerns, and review it annually.

Consult experts and review websites and existing recommended programs. One website is www.farmandranchbiosecurity.com.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)