Welcome to Health Ranch, where you can find information and resources to help you put the health and well-being of your cattle at the top of the priority list.

PI Calves: A Devastating Threat You Might Not Even See

Persistently infected calves are one of the greatest threats facing the cattle industry, but many producers don’t even know they’re in the herd.

Sponsored Content

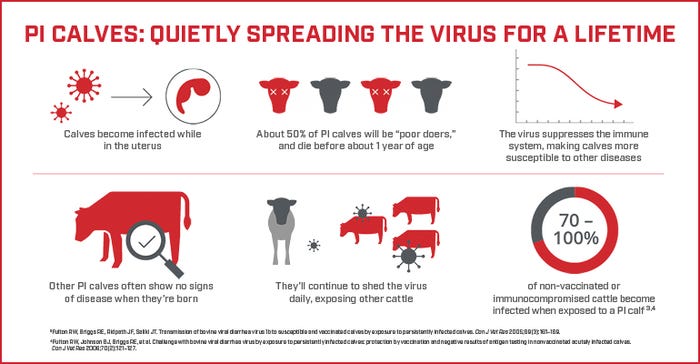

Persistently infected (PI) calves are one of the greatest threats facing the cattle industry, but many producers don’t even know they’re in the herd. “A PI calf is an animal that acquires bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) from its mother in utero,” said John Davidson, DVM, DABVP, senior associate director of beef professional veterinary services, Boehringer Ingelheim. “An infected calf can often go its whole life without showing visible signs, while still shedding BVDV and exposing the rest of the herd to the virus.”

An infected herd will experience unexplained health problems such as calves born with abnormalities, abortions and lowered pregnancy rates — there will also be more bovine respiratory disease cases and substandard weaning weights compared to uninfected herds.1,2 But the good news is that it’s never been easier to get serious about controlling BVDV PI calves. We know more about how to identify and prevent the virus than ever before.

Records are invaluable

“You can’t manage what you don’t measure,” said Dr. Davidson. “Records are an important part of any health program, but especially for identifying issues such as PI calves and BVDV problems. They’ll help you spot changes in reproductive performance, productivity and illness rates, which can then help you piece together a BVDV diagnosis sooner.”

A benchmark that speaks well to the overall health and productivity of a cow-calf operation is pounds of calf weaned per female exposed, continued Dr. Davidson. “The calculation takes into account the reproductive performance of cows and the health of calves prior to weaning. Any losses or sickness that would affect calf weight gain or cow reproduction would contribute to the final number.”

Confirm your records with diagnostics

If you think your herd is dealing with BVDV, the next step is to perform diagnostics. In large operations, veterinarians might start with pooled ear notches or blood samples, which will determine if BVDV is part of the issue. Any pools with positive results are followed up with individual tests to identify PI calves. All bulls, replacement heifers and dams of PI calves should be tested as well, and positives should be culled or isolated from the rest of the herd.

Another step that’s often missing from the herd calendar is evaluating heifers reproductively before turnout. “We have done a really good job conducting breeding soundness exams on our bulls,” said Dr. Davidson. “Now we need to implement a similar and potentially more important evaluation of replacement heifers to ensure they are sexually mature and eligible for breeding.”

Protect your herd with biosecurity

For cow-calf producers, it’s important to separate cows and heifers from animals with an unknown PI status. “Some of the costliest BVDV PI incidents that I've seen have been where a well-intentioned producer has cattle with an unknown history on one side of a fence line and unvaccinated pregnant cows on the other, not aware that fence line contact between pregnant cows and PI calves was what eventually led to more BVDV PI cattle,” said Dr. Davidson.

For producers that buy cattle from unknown sources, there’s always the risk of PI calves being present. Those infected animals can shed the virus around the feed bunk, the water trough and the chute during processing. That’s why it’s important to quarantine new additions to the herd. “It’s a good idea to keep them in their own group for 14 to 21 days, test their BVDV status, monitor them for disease and make sure they’re vaccinated before moving those cattle out into the general population,” added Dr. Davidson.

A PI prevention program starts and ends with vaccination

Vaccination is the most important part of not becoming a victim of the PI calf problem. “This is truly one of those diseases we can prevent through selecting the right vaccine and giving it at the right time,” Dr. Davidson explained. “I recommend vaccinating cows with a modified-live BVDV vaccine pre-breeding. When looking at modified-live virus (MLV) vaccines, the key question to ask is, ‘Is there a PI prevention claim clearly indicated on the label?’ It’s vitally important to understand that all MLV vaccines are not equal in preventing BVDV PI calves.”

Your vaccine selection should also reflect the latest research, which shows that Type 1b is now the most prevalent subspecies of BVDV.5,6. “Whether you’re a cow-calf, stocker or feedlot operation, when your cattle are exposed to BVDV, the odds are three to one they’re going to be exposed to Type 1b,” said Dr. Davidson. “If you’re a betting person and you take those odds, you’ll want to make sure your vaccine program lines up against that threat.”

That same pre-breeding MLV vaccine also helps cows produce antibody-rich colostrum that can protect newborn calves from BVDV for several weeks to a few months. “If a calf is born with sufficient colostrum intake from a well-vaccinated cow or heifer, producers can then vaccinate that calf around 30 days of age with an MLV vaccine that includes antigens for BVDV,” noted Dr. Davidson.

Dr. Davidson’s best advice is to work together with your beef cattle veterinarian and get to know the BVDV issues around your region — and utilize resources like BVDVTracker.com. It has an interactive heat map that makes it easy to identify if BVDV is in your area. “Our end goal as beef producers is to provide a wholesome product for our consumers,” he concluded. “Managing BVDV PI calves will help us take healthier cattle to market, reduce our antibiotic use and provide a better overall experience for the consumer.”

References:

1 Hessman BE, Fulton RW, Sjeklocha DB, Murphy TA, Ridpath JF, Payton ME. Evaluation of economic effects and the health and performance of the general cattle population after exposure to cattle persistently infected with bovine viral diarrhea virus in a starter feedlot. Am J Vet Res. 2009.

2 Loneragan GH, Thomson DU, Montgomery DL, Mason GL, Larson RL. Prevalence, outcome, and health consequences associated with persistent infection with bovine viral diarrhea virus in feedlot cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005.

3 Fulton RW, Briggs RE, Ridpath JF, Saliki JT. Transmission of bovine viral diarrhea virus 1b to susceptible and vaccinated calves by exposure to persistently infected calves. Can J Vet Res 2005;69(3):161–169.

4 Fulton RW, Johnson BJ, Briggs RE, et al. Challenge with bovine viral diarrhea virus by exposure to persistently infected calves: protection by vaccination and negative results of antigen testing in nonvaccinated acutely infected calves. Can J Vet Res 2006;70(2):121–127.

5 Fulton RW, Cook BJ, Payton ME, et al. Immune response to bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) vaccines detecting antibodies to BVDV subtypes 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2c. Vaccine 2020;38(4)4032–4037.

6 Data on file, Boehringer Ingelheim and BVDVTracker.com. Data collected November 1, 2018, through November 1, 2019.

©2021 Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc., Duluth, GA. All Rights Reserved. US-BOV-0086-2021-A

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like