High altitude disease in cattle hits the low country

Long considered just a problem at high elevations, brisket disease is now surfacing in lower-elevation feedyards.

September 16, 2015

A disease considered for many years to be a high-altitude problem for cow-calf ranchers has surfaced in the cattle feeding industry. And while researchers have been trying to pinpoint the cause of high altitude disease, also known as brisket disease, for 100 years or more, new research on why the disease is now affecting fed cattle at lower elevations reveals some interesting findings.

At high elevations, cattle have to function with low oxygen levels, which restricts blood flow through the pulmonary arteries of the lung. In cattle, the limited oxygen causes the pulmonary arteries to contract and develop thickened walls. This leads to high blood pressure in the pulmonary artery, increasing the workload on the right side of the heart.

“The disease is commonly called brisket disease due to the added fluids which would build up in the brisket and belly regions of the cattle,” says Frank Garry, professor in the Department of Clinical Sciences Integrated Livestock Management at Colorado State University (CSU). Garry and other CSU researchers, including Tim Holt, associate professor of livestock medicine and surgery, have assisted ranchers in developing selection and testing techniques to reduce the incidence of brisket disease. The selection pressures implemented by the ranchers seemed to be successful in reducing death loss in cow herds on high altitude ranches.

Right heart failure

New research and the school of hard knocks have now revealed an increase in the incidence of brisket disease at elevations as low as 3,000 to 4,000 feet — and sometimes at even lower elevations. The outcome is death loss in cattle caused by brisket disease, but at much lower elevations than previously identified by CSU researchers, and often in cattle on feed in feedlots.

The fact that brisket disease began surfacing in low altitude feedlots, where restricted oxygen flow isn’t a problem, prompted Joe Neary to develop an epidemiological study as his main doctoral research under Garry. Neary, now assistant professor of animal health and well-being at Texas Tech University’s Department of Animal and Food Sciences, conducted the research with Paul Morley at CSU, and Calvin Booker and Brian Wildman, Feedlot Health Management Services, Alberta, Canada, to measure death loss in feedlot cattle from brisket disease. Neary’s research shows that this death loss is due to right-side heart failure (RHF).

RHF is the result of the hypoxia-induced narrowing of the pulmonary arteries. This narrowing increases resistance to blood flow, resulting in increased pulmonary arterial pressures and an increased risk of RHF. Neary says to think of it like a restriction in an irrigation pipe: The restriction causes the pressure to rise inside the pipe, increasing the strain on the water pump, which will eventually fail unless the restriction is removed. Similarly, unless cattle with early signs of RHF are moved to a lower altitude, where there is more oxygen, the pulmonary arteries will remain contracted and the heart will eventually fail.

Increase in RHF

Neary’s study found a doubling of the incidence of RHF in fed cattle over an eight-year period from 2000 to 2008. “The increase in incidence of RHF should not be overlooked. The fact that we are seeing higher number of RHF cases in low-elevation feedlots is important for the industry to further study,” says Neary.

Treatment for bovine respiratory disease (BRD), date of feedlot entry, risk of BRD or undifferentiated fever and age at feedlot entry were also evaluated as potential risk factors for RHF. Digestive disorder was included as a comparison group and was comprised of ruminal bloat, enteritis, intestinal disorders and peritonitis. Here is a synopsis of the results for different evaluations conducted in the study.

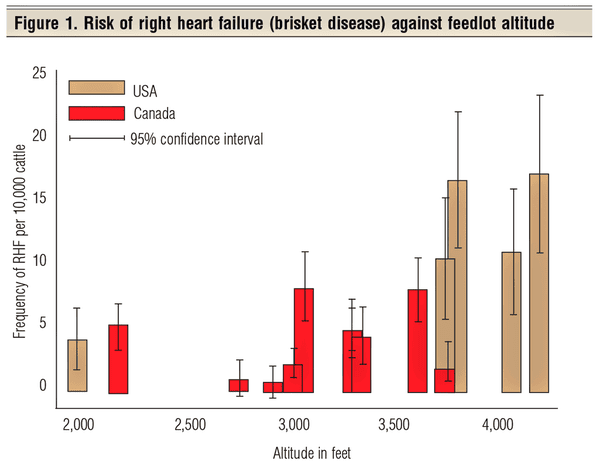

Digestive disorders: In both U.S. and Canadian feedlots, the risk of death from RHF was approximately five times lower than the risk of death from digestive disorders. However, cattle in feedlots at higher altitudes appeared to be at greater risk of RHF (see Figure 1).

Treatment for BRD at feedlot: With the industry focusing more on BRD cases, the study measured the relationship between BRD-treated cattle and RHF. Cattle treated for BRD were approximately three times more likely to die from RHF than cattle that were not treated for BRD.

18 photos show ranchers hard at work on the farm

Readers have submitted photos of hard-working ranchers doing what they do best - caring for their livestock and being stewards of the land. See reader favorite photos here.

Calf-feds vs. yearlings: “Cattle entering feedlots as yearlings tended to die earlier in the feeding period than calf-feds, but averaged across the entire feeding period they had the same risk of RHF,” Neary says. Other research conducted by Neary during his doctoral studies found that pulmonary arterial pressures, or PAP, tend to increase through the feeding period. This may explain why cattle tend to have an increased risk of RHF the closer they get to their finishing weight.

Feeding period: Death from RHF occurred throughout the feeding period, but tended to occur later in the feeding period than death from digestive disorders. The median number of days for RHF in U.S. feedlots was 133, and for bloat it was 107.

This presents a major issue to the cattle feeding industry. Cattle deaths at or near the end of the feeding period are a greater economic loss than cattle dying in the first 30 to 45 days on feed. Conclusive evidence was found in both the U.S. and Canadian feedlots that yearlings died earlier in the feeding period than calves. As Neary reports, the rate of RHF occurrence in yearlings was approximately double that of calves; however, because yearlings are fed for less time than calves, yearlings and calves had the same overall risk.

Take-home message on RHF

The study results are noteworthy to the industry for two primary reasons. First, prior to the 1970s, RHF was only reported in cattle at altitudes over 6,988 feet. Thus, a twofold increase of RHF over a 12-year period in feedlots at much more modest elevations deserves attention. What is very interesting is that the majority of U.S. High Plains feedlots are at moderate altitudes, between 3,000 and 4,000 feet, drastically lower than the elevation associated with this disease, says Garry.

Secondly, although RHF occurred throughout the feeding period, half of all cases occurred after 19 weeks, making RHF very costly to the industry. Body fat accumulation may be a risk factor for RHF, just as it is in humans. However, this remains to be determined.

Future research is underway to look more closely at identification of earlier indicators of the disease; whether or not the symptoms are confused with those of BRD; and whether or not a genetic test can be developed to identify high-risk individuals upon feedlot arrival. “Learning more about these additional components can impact many dollars in the cattle feeding business,” says Neary.

B. Lynn Gordon is a freelance writer from Brookings, S.D.

You might also like:

70 photos honor the hardworking cowboys on the ranch

Chipotle facing lawsuit for GMO-free claims

Will beef demand keep up with cowherd expansion?

Why you shouldn't feed your cows like steers in a feedlot

What's the best time to castrate calves? Vets agree the earlier the better

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)