How scenario planning helps business strategize for the unknown

Scenario planning helps you consider what your practice needs to look like in order to be successful in a range of alternative futures.

June 8, 2015

Failures of strategy are too often failures to anticipate a reality different from what we are prepared or willing to see. So, how best to challenge prevailing wisdom and assess emerging opportunities and threats?”

Jim Austin, principal at Decision Strategies International, posed this question to participants at the annual meeting of the American Association of Bovine Practitioners (AABP) last fall.

One tool to use in developing business strategy for an unknown future, Austin says, is something known as scenario planning.

Austin is a business consultant who helps a variety of businesses, including Fortune 500 companies, get to the heart of strategic challenges. AABP invited him to help veterinarians examine how they might utilize scenario planning to help imagine alternative futures in order to more effectively develop business strategies for long term success.

Up front, Austin emphasizes he’s not from agriculture. His world is business with an expertise in health care companies. But he’s worked with enough companies across a wide enough range of industries to know that scenario planning can be useful to all businesses.

Generally speaking, scenario planning involves developing a reasonable range of alternative futures for a business based upon rational assumptions about variables likely to affect the business.

“Scenario planning starts from the future and works back, and in that process ideally reveals more creative opportunities for sustainable veterinary practice success,” Austin explains. It clarifies and jump-starts discussions about specific strategies.

“Scenarios are portrayals of a series of plausible alternative futures. Each scenario tells a story of how various forces might interact under certain conditions,” Austin explains. “They are designed to open up new ways of thinking about the future, providing a framework for strategic dialogue as the basis for strategic action.”

Incidentally, Austin says business-building strategies seek the sustained competitive advantages outlined by Michael Porter of Harvard Business School in the 1970s. In Porter’s mind—and the business world since then—competitive business advantage boils down to lower cost or differentiation. Competitive advantages create value and are difficult for competitors to copy.

“Any business can meet short term needs by cutting costs, reducing offerings or playing cash management games such as extending accounts payable while driving ever more stringent accounts receivable terms,” Austin explains. “These are, at best, short term responses to changing markets or increasing competition.

According to Austin, strategies that succeed over the long term answer:

What markets, channels, geographies are we focusing on?

Within those target markets and segments, why will anyone choose us over the competition?

Preparing for an unknown future

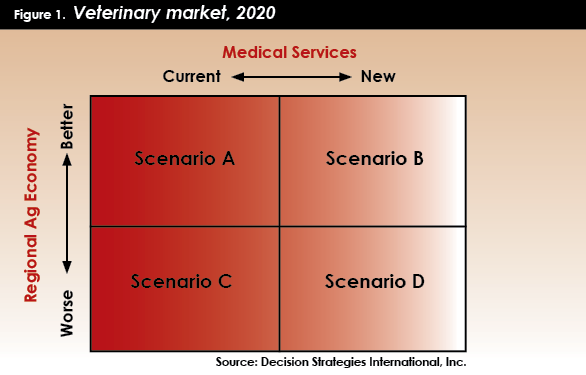

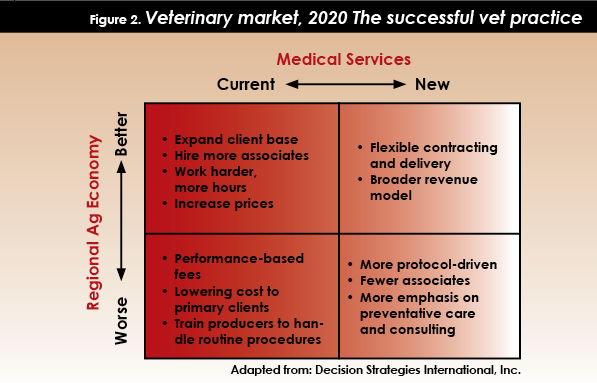

In his AABP presentation and in the subsequent proceedings, Austin offered the examples depicted in Figure 1 and Figure 2, using a couple of reasonable uncertainties faced by veterinary practices: regional agricultural economies and the level and type of services offered. Constructing a matrix, those two variables point to four alternative futures.

Assuming a practice is currently profitable, most would welcome Scenario A as the most business friendly. Regional economies are growing stronger, while competition remains fairly static. As such, strategies for growth could include working harder, expanding the client base, raising prices and maybe even adding staff in an effort to do more of the same.

Conversely, Scenario D likely would be the most challenging future. Regional economies grow weaker while competition with newer technology increases. Potential strategies for that scenario, according to Austin:

Emphasize consulting and preventative care, targeting a few large customers.

Employ fewer, less expensive staff members.

Focus on more protocol-driven practices, possibly located on-site of major clients.

Seek to establish “value” for customers as the customer defines value. This revolves around working with customers who want a high value, mutual partnership with the veterinarian.

Rather than guessing which of the alternative futures is most likely, Austin emphasizes the question becomes how you would prepare your practice to be successful no matter which future occurs.

“The typical reaction when presented a range of potential futures is to try and guess which future is more likely, especially if they challenge what we see today,” Austin explains. “But, scenarios are not predictors; they outline a range of possible outcomes for veterinarians and their clients to assess:

Where might there be unforeseen opportunities and threats?

What should my practice be prepared for, and how could we be blindsided?

Is our current strategy sustainable across multiple different futures, or is it really predicated on running harder in the current world? What happens if things change?

“None of us can know the future; we’re all prisoners of our past. It’s hard to get beyond what we’ve done in the past,” Austin says. “Scenario planning is one tool to help us step outside of today and look at things differently.”

Natural barriers to scenario planning

One thing that encourages some to ignore scenario planning is the lack of time. Even if the process identified exciting strategies, these folks reason, they have no time. Every working hour is already filled with what’s believed necessary to keep the current business going and hopefully growing.

For veterinarians and for agriculture in general, Austin recognizes another barrier is the necessary preoccupation with short term variables.

“Even though agriculture should be a medium term or a long term entity, it’s tough to get past the short term concerns, things like the weather and markets,” Austin says.

70+ photos showcasing all types of cattle nutrition

Readers share their favorite photos of cattle grazing or steers bellied up to the feedbunk. See reader favorite nutrition photos here.

Likewise, it’s hard for agricultural businesses to experiment with different business models and service offerings. Folks are understandably reluctant to take a chance that they perceive could imperil their business.

However, Austin emphasizes scenario planning and the resulting strategies are about gradual evolution within the business rather than a make-or-break, cataclysmic transition.

“It’s not about taking a 180-degree turn. It’s about spending 90-95 percent of your time keeping your current business running, but 5-10 percent of your time on a regular basis considering longer term goals and the incremental steps for achieving them. Those are the things that I think determine long term success in all businesses,” Austin says. “What do you need to be preparing for? What are the weekly, monthly and quarterly steps we should be taking while spending the majority of our time managing the business?”

Slow and steady wins the race

Characteristics of businesses most adept at creating success over many years may be different than what many assume.

Austin refers to research conducted by Rita Gunther McGrath, looking at characteristics of business growth outliers. There’s a dandy article in the January-February 2012 issue of Harvard Business Review. As well, McGrath has a website at RitaMcGrath.com. She’s a professor at Columbia Business School and a globally recognized expert on strategy in uncertain and volatile environments.

McGrath focused this research on publicly traded corporations with a market capitalization of at least $1 billion.

Only 8 percent of 4,793 companies considered in the research grew revenue by at least 5 percent per year for a five year span ending in 2009. Only 4 percent achieved a net income growth of at least 5 percent. Looking at the previous five years (ending in 2008), 15 percent of the companies had at least 5 percent growth in annual revenue and at least 4 percent annual growth in net income. Across the 10 years combined, only 10 of the 2,347 companies with qualifying performance grew net income by at least 5 percent in each of the 10 years. Only five grew revenue and net income every year.

According to McGrath’s research, companies that prosper over the long term are stable, yet innovative. They evolve gradually but adapt quickly. They make small bets early on to diversify and try new things or explore new markets. Based on the outcome, they invest more or pull the plug fairly quickly—no beating what could be a dead horse. They focus on growing their core business but diversify with other enterprises related to the core business. They manage resources centrally and maintain management flexibility. They keep their talent and maintain senior leadership. They have reliable customers. They’re consistent in all that they do.

This was true despite the industry served by the company, company size or age. It was true whether the company served markets regarded as emerging or mature, and whether the company was a start-up or the product of mergers and consolidation.

“When things go our way, we like to think it’s because of what we did. When things go against us, we like to blame it on external challenges,” Austin says. “We’re overconfident of our ability to manage external challenges.”

Scenario planning is a tool that helps understand how external forces could create different futures for a unique business so that business strategies can be developed more effectively.

“How can this be integrated into your tool kit as enterprises become larger and more integrated?” Austin asks.

You might also like:

Ouch! Find out what Canada, Mexico want for COOL retaliation figures

Can ranching be sustainable without profits? Burke Teichert says no

How to prevent & treat pinkeye in cattle

Fed cattle market is 2014 market over again

5 essential steps for fly control on cattle

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)