It's not hopeless: Addressing mental health in rural America

Access to care is a common challenge, but there is help available for those dealing with stress and depression.

On the outside, everything seemed fine. It may sound like an overused expression, but for most who knew Trevor Lienemann, everything did seem fine — if not more than fine.

Starting with humble beginnings with only six aged cows and working as an accountant by day, he had built a name for himself as a successful seedstock and cow-calf producer south of Lincoln, Neb.

He invented and marketed Bextra bale feeders. His name appeared in numerous farm and ranch publications and TV programs, and his family hosted the 2016 Cattlemen's Ball of Nebraska — an event that raised hundreds of thousands for the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Fred and Pamela Buffett Cancer Center, and brought country music legend Clint Black to their front yard.

But despite these accolades and being well-known in the Angus cattle and Nebraska agriculture communities, Trevor dealt with a challenge that's all too common: depression. While not unique to agriculture, the nature of the ag business poses a unique set of challenges.

"In the community, people knew who we were. They knew what they saw of us. What they don't know was the struggle it took to just get out the door," says Torri Lienemann, Trevor's wife of 26 years, who worked as the director of graduate studies in special education at Concordia University, Nebraska, in addition to managing the Lienetics ranch and the Bextra business. "Every picture that's taken, every event that we were at, there were always the hours before, the minutes before, the weeks leading up to, that were a huge, huge struggle."

Throughout his battle with depression, Trevor's family stood by his side, much like they had at every bull sale, helping with chores on the ranch every day and preparing for numerous meetings and events they participated in as a family.

Sadly, Trevor died by suicide in November 2018 at age 51.

Trevor, like many who battle depression, was highly driven and strove for perfection in many facets of life. However, that perfectionism also could be a strain on his family and himself.

"On the other hand, we also wouldn't have done the things we had if not for Trevor's perfectionism — he had this sense that things could always be better," Torri says. "He was never quite satisfied with anything, which created a lot of difficulty, but also helped us progress in a lot of areas."

It also was difficult for Trevor to admit his diagnosis. He had been asked to go to counseling, but resisted, concerned it would be difficult to find a counselor that understood rural, agricultural life and the unique stresses that go with it.

"[He thought], 'No one understands the ag life,' " Torri says. "'They just see things from their office. They don't understand the responsibilities that come along with raising livestock and being involved in agriculture.' So, he refused to go."

In 2017, when going through a rough bout of depression, Trevor reached out to a friend, who put him in touch with a local pastor with an ag background, who then recommended a counselor.

"That made a huge difference in his life, because he found that relationship with God that he never had before," Torri says. "The anger, the judgment and feeling like we needed to earn that approval, it all went away with counseling and finding God. I think back, and if Trevor would have gotten help sooner, before it had gotten so bad, I think I would be telling a different story."

Breaking the stigma

Concerns over finding the right counselor are legitimate, says Ted Matthews, director of Minnesota Rural Mental Health, who has more than 30 years in mental health practice.

"I've worked with several farmers over the years who said, 'I tried counseling, and it didn't work.' They'll tell me why, and most of it is the logic of farmers is not the same logic," Matthews says. "If a farmer has a farm worth $4 million, they're losing money every year, and the therapist says, 'You've been losing money, why don't you sell the farm?' That might sound logical to a therapist, but not to a farmer. They feel they've let down their family. It's not at all what a farmer needs to hear."

Another factor is the stigma associated with mental illness, and many don't seek treatment until they reach a breaking point.

"If I had a nickel for every farmer who said, 'I didn't think I was bad enough off,' as if somehow you have to reach a point of no return to get help — why?" Matthews asks. "Why do we always think 'mental illness' when we hear 'mental health'? When I think about mental health, why wouldn't I think of being happier than I already am?"

Tina Chasek, associate professor in the Department of Counseling and School of Psychology at the University of Nebraska-Kearney and director of UNK's Behavioral Health Education Center of Nebraska, notes one of the most commonly cited risk factors: the unpredictable nature of agriculture.

"You have all that financial stress and pressure, which is extremely difficult because people in agriculture build their identity on their ability to work the land," Chasek says. "When they have bad years, it becomes very personal and you feel like you failed. Another thing that's unique is that family are often business partners. Family tension in succession planning can be a huge deal. Support comes from family, but when those relationships are strained, that's a factor."

And while much of the discussion on mental health in agriculture has focused on men, Chasek notes women in agriculture take on a heavy burden all their own.

"Women in agriculture are sometimes called third-shift workers," Chasek says. "They work outside the home to provide a steady income and insurance benefits. Then they take care of the family and work on the farm, in addition to being social support. So, they have three jobs. If a male farmer is going to talk, it's usually to his wife. Women on the farm often take care of everybody's emotional needs. So, there's a huge burden on them as well."

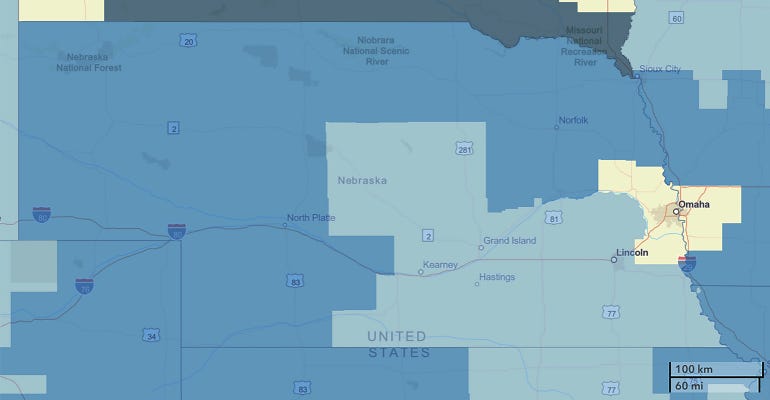

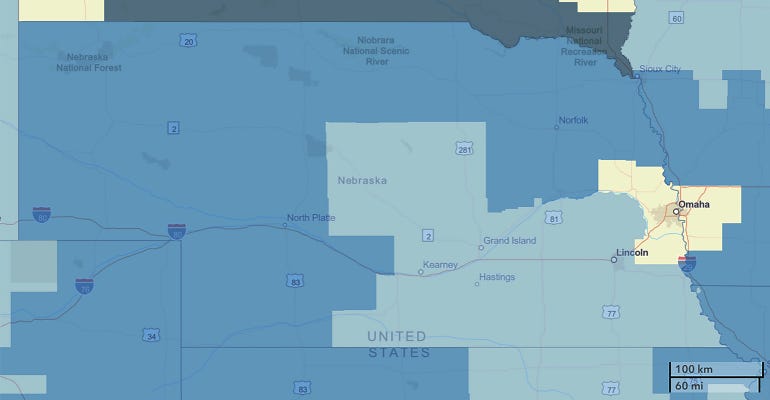

When farmers and ranchers do seek treatment, there's often limited access. County-level data from the U.S. Health and Services Administration indicates that all but five, or 88 of Nebraska's 93 counties, are considered mental health professional shortage areas — and those five are in the Omaha metropolitan area.

Shortage areas are determined based on the number of providers available relative to demand, and Chasek notes a county may be labeled a shortage area because it lacks a certain kind of provider. For example, there may be a shortage of psychologists, but not licensed mental health providers, who can provide similar services.

"If you drew a line from Grand Island north and take all the providers in Nebraska practicing everywhere west of Grand Island to the Panhandle and outside the Tri-Cities [Grand Island, Kearney and Hastings], it's less than 2% of all behavioral health providers in Nebraska," says Chasek, citing data from the Behavioral Health Education Center of Nebraska.

RURAL SHORTAGE: This map shows Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas in Nebraska designated by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration. While counties highlighted in gray are non-shortage areas, light blue counties have a HPSA score of 1-13, darker blue counties have a score of 14-17, and the darkest counties have a score of 18 and higher.

While not always ranked as the occupation with the highest risk of suicide, farmers often are ranked among the highest, although Chasek notes these rankings are subject to change.

A 2016 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found "farming, fishing and forestry" had the highest suicide rate of any occupational group. However, that report since has been retracted, and a new report in 2018 found that "farming, fishing and forestry," which includes farmworkers, ranked eighth in 2012 and ninth in 2015, respectively.

Meanwhile, the "management" group, which includes farm and ranch managers, ranked 17th and 15th in 2012 and 2019, respectively.

A 2014 University of Iowa study indicated that from 1992 to 2010, farmers and ranchers had an average rate of suicide 3.5 times the general population.

However, several characteristics of agriculture are beneficial for mental health.

"Being outside and getting exercise is awesome for your mental health," says Chasek, who lives in Hildreth, Neb. "Having close relationships is helpful. In my town, every morning at 6 o'clock, without fail, there are all these farm trucks at city hall to grab coffee. That's one of the best things the ag community does — they support each other very well, even if they're not at the elevator and saying, 'I'm going to see my therapist.' They're talking about what's going on in farm policy or at the farm."

The characteristic resilience in the face of challenges is another boon, and most farmers and ranchers have a strong sense of meaning and purpose.

Chasek emphasizes depression is a common illness. Statistics from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, indicates more than 7% of U.S. adults had a major episode of depression in 2017. And while it may feel hopeless during a depressive episode, most people who seek treatment will recover.

Not all doom and gloom

Recovery is possible even in the most remote parts of the U.S., where access is limited, such as the Nebraska Sandhills. Take Ty Walker, for example. Walker, 34, grew up and attended high school in Arthur, Neb., and attended Eastern Wyoming College in Torrington.

He works on a ranch between Thedford and Valentine and is active in the ag community as a member of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln's LEAD (Leadership Education/Action Development) Class 36.

"I struggled with depression, anxiety and alcoholism for a number of years," Walker says. "I struggled with it by myself, because I was ashamed to ask for help. You don't have to struggle alone, and you shouldn't be ashamed to look for help that can put you on the path to a better quality of life. I was talking to a friend who was struggling, and I realized even between two close friends it was hard to talk about, and that shouldn't be the case."

That's why Walker began speaking out about mental health.

Walker suffered concussions playing football and riding broncos and bulls in rodeos in high school and college, and he believes these injuries may have played a role.

"I didn't know at the time, but after a lot of research on CTE [chronic traumatic encephalopathy] came out, I started noticing the symptoms I had, and depression was definitely one of them," Walker says. "I'd come closer than I'd like to think a number of times, and I feel fortunate I'm still around. I never made an attempt, but it was always there. When I heard about the suicide of an acquaintance, it jolted me into thinking, 'I've got to get a hold of this thing, or it's going to win.'"

So, despite his hesitation, he decided to seek help.

"Once I did, I learned you can't tough out a brain injury or a chemical imbalance in your brain," he says. "Clinical depression isn't something you can just tough out. If medication helps address it, why wouldn't you? I was pretty skeptical about seeing a counselor. At the time, I perceived asking for help as weak. I also misunderstood how it might go. I thought to myself, 'What good is talking going to do?'"

Once he went, Walker says counseling helped direct him to steps and resources to aid his recovery.

This includes medication, diet and exercise, practicing meditation and mindfulness, and studying stoic philosophy — a means of reframing perception of the world, actions and their consequences, and handling things that can't be changed. He's also learned to play guitar and practices mixed martial arts. Both are activities that have been shown to aid in mindfulness.

Of course, every person is different — the steps that can or should be taken largely depend on the individual. That's why it's important to seek therapy along with medication.

"For someone that's struggling and is in a rough spot, it might seem overwhelming to think about all of these steps," Walker says. "Those are steps I've gradually added over the years. The first step is being able to talk about it — whether it's a friend that has experience with it or a counselor. There are steps you can take to lead a better quality of life. I can attest to it. It has worked. It might be different for different people, but there is help out there. There are things you can do. It's not hopeless."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)