Multi-Pronged Border Effort Fights Fever Ticks

A multi-pronged effort at the border continues to wage the long-running war against fever ticks.

July 1, 2011

In the 1800s, Kansas Jayhawkers stopped Texas cattle herds from spreading it northward. In 1906, a massive eradication program began and federal horsemen started patrolling the border to halt it. By 1943, eradication was virtually complete. But that status is under threat.

Cattle tick fever was the target – and still is – as state and federal agencies work to control a fearful disease that once killed more than 15,000 cattle annually. Today, however, Mexico fever tick inspections must deal with the extra challenges

induced by the smuggling and border warfare being waged by Mexican drug cartels, as well as the high cattle prices that make rustling cattle across the border worth mucho dinero.

Dee Ellis, Texas Animal Health Commission (TAHC) executive director, heads that state’s efforts to cool down fever tick threats. With the state and federal tick inspection and treatment programs in place, he stresses that buyers of Texas cattle in other states can be sure they are fever-tick free.

TAHC works in conjunction with USDA’s Animal Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) Veterinary Services (VS) to assure all cattle within an eight-county region along the Rio Grande River are free of fever ticks before they’re shipped northward. They’ve had to provide “tick riders” a hand in spotting and corralling tick-infested cattle and wildlife.

Thankfully, bovine Babesiosis – “cattle fever” – isn’t common to most producers. But if uncontrolled, Ellis says the infectious protozoa organism targets red blood cells and causes high fever, severe anemia, loss of appetite, weight loss, weakness and red-colored urine.

TAHC says more than 100 premises in deep South Texas were infested with the fever tick in 2010.

“Thankfully, though, no actual cases of babesiosis were documented in cattle on any Texas’ premise,” Ellis says. “For clinical disease to occur you must have the fever tick present, babesia organisms in the blood of cattle they feed on, and then other naïve cattle in the same pasture that the fever tick’s offspring can spread the disease to. Acute cases may result in death rates of 50-80% when detected.”

USDA tick riders, who’ve rounded up strays along the border for more than a century, haven’t been able to ride certain stretches of the river on a consistent basis during 2010 and 2011. Danger from drug cartel violence caused USDA to stop testing cattle on the Mexican side of the border last year. That put added pressure on tick riders, who must patrol the 500-mile tick bumper zone.

“What’s happening in Mexico is terrible,” says Under Secretary of Agriculture Edward Avalos, who rode with tick riders to observe the situation this spring. “It has impacted out ability to do our job in Mexico.”

Ernie Morales, TAHC chairman and operator of the 10,000-head Morales Feed Lot near Devine, TX, says the stray cattle that slip by tick riders along the massive border, as well as white tail deer and other exotic and native wildlife, are likely what cause the spread of fever ticks to ranches in the region.

“TAHC is working with USDA to assure that infected cattle are treated for fever ticks and safe for movement out of the region,” Morales says.

Dip vats get a workout

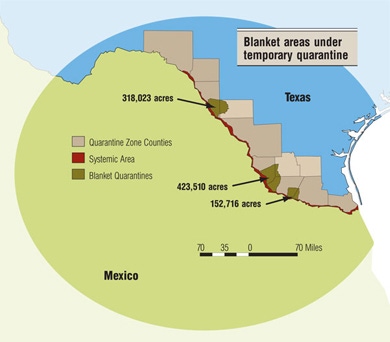

Processing of cattle is enough of a chore for any rancher, but those in the quarantine area (see adjoining map) have several more headaches.

Portions of eight Texas counties, including Val Verde, Kinney, Maverick, Webb, Zapata, Starr, Hidalgo and Cameron, are located in the permanent fever tick quarantine zone along the Rio Grande. Cattle can’t be moved out of the region unless tested and treated for fever ticks.

“Cattle moving out of the permanent quarantine zone are inspected for presence of fever ticks by USDA inspectors and treated with a topical pesticide by immersion in a dip vat,” Ellis says.

“Co-Ral (coumaphos insecticide) is the most effective product for use in dip vats and is required for movement from the permanent quarantine area and other quarantined herds. Cattle in infested herds on a cleanup plan may be treated with Co-Ral, or injectable Dectomax.

“Both products are equally effective. Co-Ral doesn’t have a withdrawal prior to slaughter, but Dectomax does.”

Ellis stresses that “the inspection and treatment must be documented on an official permit for movement, which must accompany the shipment.”

U.S. vaccine in 2012?

There’s no vaccine available for use against tick fever in the U.S., but a vaccine is in use in Australia and shows promise. “It’s still undergoing evaluation for efficacy,” Ellis says, noting that USDA’s Center for Veterinary Biologics is the regulatory agency in the U.S. testing safety and efficacy of the vaccine product.

“Most states including Texas also require approval of some ‘biologicals’ by the state veterinarian. Once the Australian vaccine trials are completed, that vaccine will obviously be considered for use in Texas and the U.S.”

TAHC has also requested an efficacy study of the Cuban vaccine (GAVAC) in partnership with the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Kerrville, TX.

“Preliminary studies indicate the vaccine shows a high level of protection against one strain of the cattle fever tick (annulatus), but relatively low efficacy against a second common fever tick (microplus),” Ellis says.

The next step in the evaluation is a field trial in naturally infested herds along the Texas border sometime this year. “TAHC is also exploring the possibility of the creation of an autogenous tick vaccine,” he adds.

“It’s anticipated that eventually one of those vaccine options will be provided to the ranchers located in the permanent quarantine zone, at no cost, as another tool to fight the tick. Hopefully this can happen within the next year.”

Don’t blame Mexican feeders

Along with his feedyard, Morales also runs stockers and often buys Mexican feeder cattle, which perform well in the South Texas region. While some try to blame the Mexican feeders for spreading fever tick danger, Morales strongly disagrees.

“Trying to correlate movement of fever ticks into Texas through Mexican imports is wrong. It’s just not happening,” he says. “With our strict program to test and dip imported cattle at border pens, I don’t think the source of fever ticks has anything to do with Mexican feeder cattle.”

Temporary holding pens have been built by TAHC and APHIS personnel near the border cities of Laredo, Eagle Pass and Pharr. Avalos says the temporary pens are helping stop fever-tick spread without halting movement of Mexican cattle into Texas.

In addition, USDA hopes to build 8-ft. fences along and near the Mexican border to further limit movement of tick-carrying wildlife into pastures already declared tick-free.

“Any fencing that prohibits the accidental introduction of fever ticks into clean pastures by wildlife movements would be beneficial to the eradication program,” Ellis says. “Many ranchers have built their own game-proof fence for this reason. USDA has proposed a cost-share fencing initiative that is undergoing environmental studies at this time.”

However, the timetable for this fencing program is at least 2-3 years away, he adds. And the border war against fever ticks is likely here for years to come.

“TAHC and VS are doing a good job of protecting the rest of the state from the fever tick accidentally being reestablished outside the Texas-Mexico border,” Ellis concludes. “But continued vigilance will be needed for an indefinite period of time.”

You May Also Like