Beef marketing system buffeted by challenges

The COVID crash was fast and furious. How fast prices recover and return to normal depends on how well the U.S. keeps COVID-19 under control.

July 13, 2020

Without a doubt, the delicate cattle and beef marketing system we have in the U.S. is being challenged like never before. This month, my study herd manager asked me to brief him on the beef market beyond the ranch, with specific emphasis on the consumer aspect of the beef market.

I summarized some of the data I receive each week in a newsletter titled the Daily Livestock Report, published by Steiner Consulting Group. Here is what I sent to my study rancher.

Meat production (beef, pork and poultry) was up in March 2020, with “all” meat production up 10% over last year in the last week of March 2020. Saturday slaughter was especially high in late March and served to increase slaughter in high demand times.

There certainly was no indication of a protein shortage in late March, or even down the road. In fact, beef production was up 13.7% over a year ago in the last week of March.

But in late March, things started to change — and change rapidly — for U.S. consumers. COVID-19 hit in several states, and some consumers immediately shifted into panic buying mode. Panic buying brought on spot shortages of some consumer-demanded products in some markets.

First it was toilet paper, and then disinfectant and baby wipes. Home disinfectants soon joined the panic list. This was about the time my wife and I elected to migrate from our Arizona winter home to our Idaho summer home. Our unusual trip experience back to Idaho was summarized in the May 2020 Market Adviser.

Even with increased COVID-19 in late March and early April, there was no indication of a protein shortage. Then, as the coronavirus got worse, stay-at-home orders were made; restaurants closed down, stopping all food service beef demand; and all meals were consumed at home.

The supply chain, however, could not instantly change from restaurant-supplied meats to home-cooked meats. Consumers rapidly perceived a shortage of meats. The demand for home-prepared meals skyrocketed, causing the demand for home-consumed meats to skyrocket.

The marketing system had to make a dramatic change from restaurant deliveries to grocery store deliveries, but the products demanded were different. The supply channels were different. There was an ample supply of meat available, but not in the form consumers wanted. In order to ration grocery story meats, the price started to go up.

Packers and suppliers needed to balance rapidly increasing grocery store retail demand with a sharp decline in food service demand. The “just in time” supply system was changing, and it was asked to do so overnight.

It became impossible to supply all the meat demanded by grocery stores nationwide. At the same time, consumer meat prices approached double from a year ago, leading to consumer panic buying.

Beef plant shutdowns, more complications

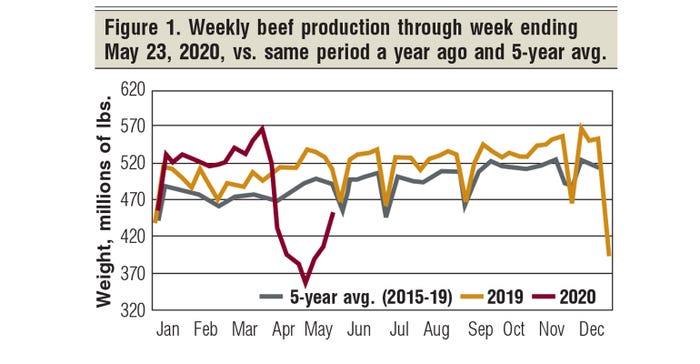

Then on April 13, the JBS Greeley beef plant closed due to some of its workers contracting COVID-19. Soon after, other slaughter plants followed with the same problem. Due to the limited number of slaughter plants in the U.S., by May 5, beef production was down 687 million pounds carcass weight and 481 million pounds retail weight (Figure 1). That was 12,000 truckloads of retail beef!

As meat markets entered uncharted waters with COVID-19, concerns increased about the ability of packers to process meat in a timely manner.

President Donald Trump declared meatpacking a “critical industry,” and the slaughter industry immediately started a massive coronavirus testing program, enabling meat processing plants to start back up processing in a relatively short period of time.

By mid-May, the ground beef price was only about 14% higher than two weeks earlier. Retail margins, however, were negative. As markets adjust, retail prices will have to cover retail margins, so consumer prices will undoubtedly go up.

On May 1, the total number of cattle on feed in lots of more than 1,000 head was 5.1% lower than last year. But there was a notable backup of cattle, both in the feedlots and outside the feedlots. Feedlots sharply reduced their placement of feeder cattle in March and April. This was driven by COVID-19.

The supply of slaughter-ready cattle on April 1 was 9.2% above a year earlier, greatly affected by the decline in slaughter capacity in April.

We can expect the number of 150-plus-day cattle on feed as of June 1 to go up substantially, putting downward pressure on June fed cattle futures even as wholesale beef values are at very high levels. It is going to take a while to work through the extra fed cattle numbers this summer.

Let’s bring the discussion back to my study manager’s ranch business. The drama of the beef processing industry’s struggle with COVID-19, the switch away from restaurant consumption and consumer hoarding have directly impacted slaughter cattle prices and local sale barn feeder cattle prices. Figure 2 illustrates the slaughter cattle price impact going into May. The bars for June 2020 through December 2020 project the price impact for slaughter cattle through the end of the year.

I am not projecting a return anytime this year to the higher slaughter cattle prices we saw in January and February. How fast prices recover and return to normal depends on how well the U.S. keeps COVID-19 under control.

The beef industry needs people to start eating again at restaurants! We need a COVID-19 vaccine, and we need it fast!

Hughes is a North Dakota State University professor emeritus. He lives in Kuna, Idaho. Reach him at 701-238-9607 or at [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)