How Futures Work: Options and risk management

Using options can protect you from downside risk while allowing upside potential.

June 12, 2019

Industry At A Glance is running a series around the basics of futures and options to help producers better understand the basic mechanics of implementing risk management. Last week’s column outlined the basics surrounding futures contracts and the concept of basis.

With that in mind, it’s helpful to provide some fundamental definitions to frame this week’s discussion:

Futures contract: Standardized contract obligating participants to make (or take) delivery

Options contract: Right to buy (call option) or sell (put option) underlying futures contract

Strike price: Price of underlying contract at which call or put option would be exercised.

Premium: Price of option

For example’s sake, our focus is upon risk management for fed cattle. And because we’re looking to implement risk management on the selling side (“short”), the discussion highlights the use of put options—the right to sell futures contract.

Purchasing a put provides an insurance policy for a cost, which is the premium, establishing a price floor for sellers. But it also enables the ability to capture upside potential, thereby eliminating opportunity cost associated with straight hedges with futures contracts.

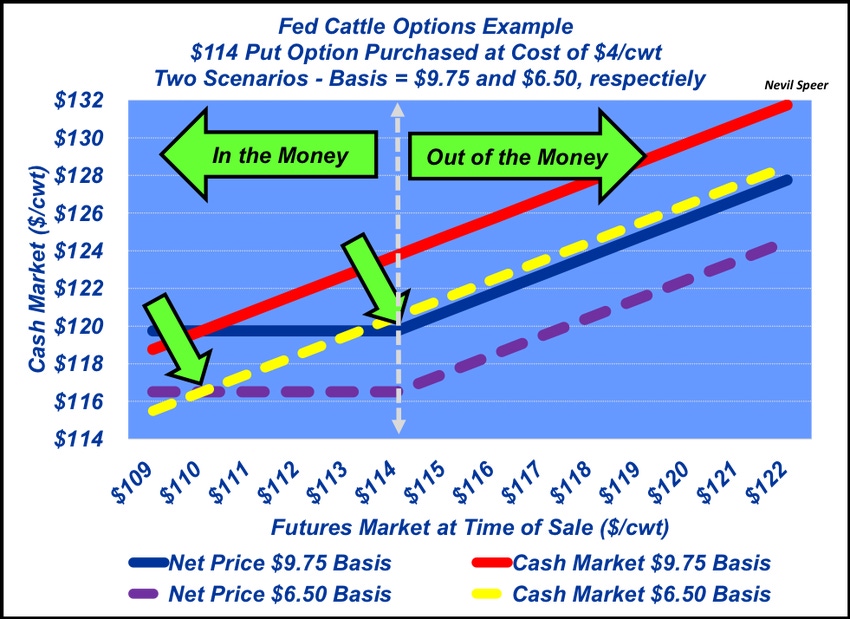

Last week’s example utilized cattle placed between mid-November and mid-December to be marketed in early- to mid-May against the June live cattle contract. At the time of placement, a $114 (strike price) June live cattle put cost $4 per cwt.

That purchase allows the feedlot to sell the underlying futures at $114 per cwt if desired. The seller of the put is obligated to provide a short position in the futures market if the option is exercised. Because the put cost is $4 per cwt, the net selling price would be $110 per cwt if exercised.

During the past five years, May’s basis average has been positive $9.75. Based on that historical information, the expected selling floor would be $114 per cwt (futures contract) less $4 per cwt (cost of option contract) plus $9.75 per cwt (positive basis), thereby equaling $119.75.

The put would be exercised at any point in which the futures market at sale time is LESS than $114 per cwt. Thus, the put would be “in the money.”

Meanwhile, if the futures market rises above $114 per cwt, the put would NOT be exercised (“out of the money”) and the seller can take advantage of upside potential in the cash market, although always $4 per cwt behind cash due to the initial cost of the put.

As explained last week, basis risk is always present. Case in point, fed cattle basis (cash minus futures) declined from $9.75 in early May to $6.50 just two weeks later and will seasonally continue to erode as we get closer to June expiration.

All the principles around the put still exist, but the absolute selling price is proportionally less due to declining basis. That is, with a $6.50 basis, the floor is now $116.50 per cwt—$114 per cwt put less $4 put cost plus $6.50 basis.

The graph compares utilization of puts versus the cash market at varying basis levels. The two examples illustrate the concept of building a floor price and the ability to track the market higher.

A couple of broader key principles are important when considering the purchase of any option contract: Option values (not the strike price) inherently decline over time as we get closer to expiration, and; increased market volatility increases the value of options.

Next week we’ll look at key differences between hedgers and speculators and their respective positions in the market.

Speer serves as an industry consultant and is based in Bowling Green, Ky. Contact him at [email protected]

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)