Nearly 75% Of U.S. Cattle Are Black-Hided; A Look Behind The Numbers

Several factors influence USDA’s black-hided numbers.

June 22, 2012

Black-hided. It’s the initial requirement for more than 80 beef brands certified by USDA.

That also means it’s the first limiting factor for supply of programs like the largest and longest-running of those: the Certified Angus Beef® (CAB®) brand.

Total federally inspected fed-cattle harvest is the first number CAB packing director Clint Walenciak looks at. “The matrix of what drives total CAB pounds starts with that, and then it would be the percent that’s black-hided,” he says. “Then we apply our 10 carcass specifications to narrow that down even further, so that we’re running right at 24% today.”

That’s why the company has tracked black-hided numbers since 2004, and USDA now reports a percentage of “A-stamp” carcasses in the harvest mix.

“The fragmented nature of our industry means the only place we can truly capture how many cattle in the U.S. beef cattle supply are black-hided, or Angus-influenced to some degree, is at the packing plant level,” says Lance Zimmerman, CattleFax analyst.

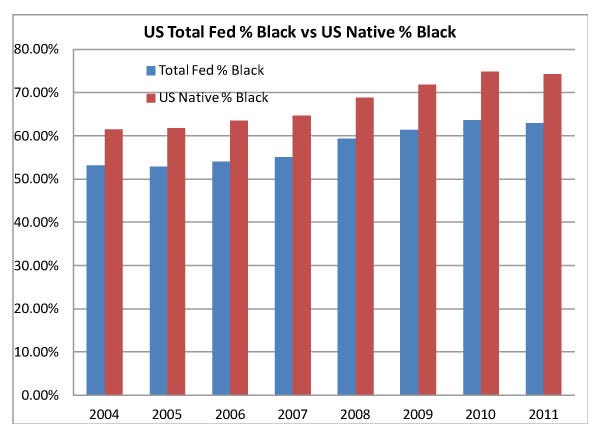

That number has trended upward since 2004 (see chart) to level off and settle back to 62.9% last year, an obvious majority. Yet many are surprised the percentage isn’t higher.

“When you look at different surveys that estimate bull turnout in the population, they typically run about 70% Angus, and Angus bull sales continue to be strong, so some of those numbers are counter to what we’re seeing,” Walenciak says.

Indeed, the 2011 Western Livestock Journal Bull Turnout Survey had the Angus breed leading all others with 71.5%, and that was down a bit from the 2009 mark.

So is it a case of bad math?

Walenciak and Zimmerman say no. It’s a matter of looking at the number of native black-hided cattle compared to outside factors like Mexican and Canadian feeder cattle imports, Canadian finished cattle imports and fed dairy cattle.

Those four categories can have a “dilution effect,” says Walenciak. “As we see the U.S. fed [harvest] decrease the past year-and-a-half, those numbers become a higher percentage of the total.”

They made up 16.1% of the total harvest mix in 2004 compared to 18.4% in 2011.

Walenciak and his team put a value on the sway each has on the A-stamped percentage.

For example, Canada lags the U.S. in black Angus influence, so they applied a 40% black factor to total imported Canadian fed cattle for each year. They estimated Mexican feeder cattle at 20% black.

“That’s based generally on what we understand Angus genetics to be there,” Walenciak says.

Such adjustments arrived at a native black-hided percentage 12 points higher than the all-inclusive USDA number. It rose from 61.5% to its peak of 74.9% in 2010, and stood at 74.2% last year.

“The upward trends command a greater portion of my attention than the steady to slightly softer year that may have showed up in 2011,” says Zimmerman.

Judgments based on just one year are “dangerous,” he adds, especially considering a smaller cowherd and drought effects. Still, many are intently watching that dip in numbers.

“We have our best guesses on why that’s occurring, like slight heifer retention and those being a very high percentage black,” Walenciak says.

Although there’s no way to track that, Zimmerman agrees it makes sense.

“If we were just putting black animals into the fed cattle mix [without retaining heifers], eventually we’d have seen those numbers drop off, but we’re clearly producing more black cattle. Most likely that is not only from Angus bull purchases, but from retaining those offspring in the herd as well.”

It’s easier to put numbers to other variables.

Zimmerman notes the wide year-to-year swings in some of those subset populations, like last year’s Mexican feeder cattle imports at a record high for the 2004-2011 timeframe, at 1.4 million.

“A large part of that influence was just like our friends in Texas, Oklahoma and New Mexico, further south that drought continued,” he says. “The Mexican producers were no different in that they needed to liquidate cattle, wean early and send to market. That contributed to a much larger number of Mexican cattle than we’ve seen before.”

But in 2008, Mexican feeder imports were as low as 702,873. Last year’s 1.4 million represents a much larger influx of a much more diverse cattle population.

Exchange rates and policies have added to the variability in Canadian imports, both feeder and fed cattle, from very little in 2004 to peaks in 2007 and 2008.

“They have been going through their own cowherd reduction the last few years,” Zimmerman says. “So those give-and-takes can have a significant influence on this hidden calculation of the black-hided number.”

Despite all that “noise” in the data, there are two messages this black trend reveals.

“If you look at the ’90s and early 2000s, it was very common for a producer to market his cattle as ‘good, reputation blacks,’” Zimmerman says. “This shows that those good reputation blacks are pretty common in the marketplace. It’s really important for a producer to take advantage of any extra detail and data he can get his hands on to show his Angus cattle are worth more than just average black-hided cattle.”

Walenciak hopes ranchers will make more of those top-level animals, because just being black-hided isn’t enough.

“As we grow the demand for high-quality beef, it’s very important for us to keep that consistent supply so retailers and restaurateurs can have confidence in the reliability of that supply,” he says.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)