The Story Of Beef From Gate To Plate

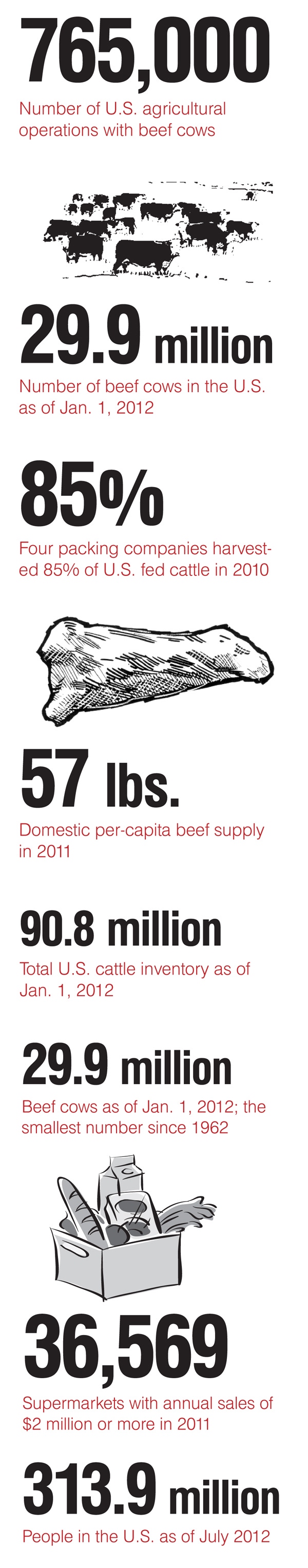

BEEF embarks on a year-long series to define and explain the long and interrelated industry path of beef from gate to plate. View an infographic that breaks down important industry numbers here. View part two of the year-long series here and part three here.

July 27, 2012

Fragmentation is both the blessing and curse of the U.S. beef cattle industry.

The equity required for production – land, feed, cattle, etc. – is so steep per head that the odds of any single entity ever owning a significant percentage of the industry, as is the case in pork and poultry, is remote at best.

In other words, while different segments enjoy comparative advantages at different points of the supply cycle – such as cow-calf producers currently – no single sector and no single player within a sector can drive the market.

Plus, there are 765,000 operations with beef cattle, according to the 2007 USDA Agriculture Census (the most recent available), across the U.S., which also spreads production risk.

With that said, calf production is concentrated in fewer, larger herds. According to USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS), only 9% of beef cattle operations have herds of 100 cows or more, representing 51% of the total U.S. beef cow inventory.

“Most of these were small, part-time operations. About a third of farms that raise beef animals had a beef cow inventory of less than 10 cows, more than half had fewer than 20 cows, and nearly 80% had fewer than 50 cows,” say William D. McBride and Kenneth Mathews, Jr. They authored “The Diverse Structure and Organization of U.S. Beef Cow-Calf Farms,” an ERS study published last year.

As of Jan. 1, 2012, there were 29.9 million beef cows in the U.S., 3% fewer than the year before and the fewest since 1962. The total cowherd (dairy and beef) on Jan. 1 was 90.8 million head, 2% less than the prior year and the smallest total cowherd since 1952.

Fragmentation clouds direction

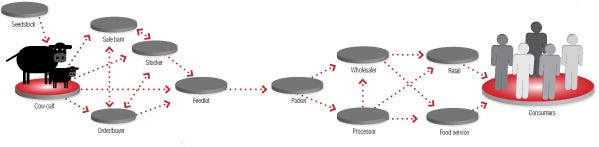

On the other side of the ledger, fragmentation makes it difficult for the industry to choose a direction (cattle size, carcass quality, etc.), let alone achieve it. And, in addition to the number of cattle operations, a veritable maze of potential pathways exist beyond the ranch gate.

For instance, although most market calves will end up in a feedlot sometime after weaning, some may stop off at a backgrounding yard first, spend time in someone’s stocker pasture, or both. Or they can take other routes, under the same or different ownership.

There were approximately 17,000 U.S. feedlots with a capacity of 1,000 head or more as of Jan. 1 of this year, according to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service. Only 275 of those feedlots have a capacity of 16,000 head or more. Feedlots with a capacity of 1,000 head or more represent less than 5% of all feedlots but market 80-90% of the fed cattle each year, according to ERS.

From the feedlot, cattle flow to beef packers. The four largest beef packing organizations accounted for 85% of the steers and heifers slaughtered in 2010, according to the 2011 annual report from USDA’s Packers and Stockyards Program.

All told, 33.5 million head of cattle were slaughtered under USDA inspection last year, according to statistics compiled for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Associa-tion (NCBA) by CattleFax. Those cattle churned out a total of 26 billion lbs. of beef. Of that, 2.35 billion lbs. were exported.

According to the latest Census of Agriculture, cattle and calf sales generated about $61.2 billion in 2007. That accounted for about 20% of the total market value of agricultural products sold in the U.S. That ranks beef first in sales among agricultural commodities.

More than half of the value of cattle and calf sales come from five states, according to the 2007 Ag Census: Texas, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa and Colorado. In terms of beef cow numbers, the top five states are: Texas (4.37 million), Nebraska (1.88 million), Missouri (1.86 million), Oklahoma (1.73 million), and South Dakota (1.61 million).

From the packer, beef moves to further-processors, some owned by beef packers, then into retail or food service channels, often by way of a massive, though concentrated, food distribution system.

There were 36,569 supermarkets in 2011 with annual sales of $2 million or more, according to the Food Marketing Institute. There were 580,852 U.S. restaurant units in the fall of 2011, according to The NPD Group. Now, throw in other areas of food service that procure beef, be it schools, the military, hospitals, etc.

Ultimately, the beef that’s not exported winds up on the dinner plates of a current U.S. population numbering 313.9 million people. In round numbers, per-capita beef supply last year was about 57 lbs.

The end result is that domestic consumers can buy beef at retailers and through food service every day of the year, in about any form and volume they want.

To say that the overwhelming complexities necessary to achieve this reality are miraculous would be an understatement. No one could sit down with a roomful of the brightest minds and concoct such a scheme that works largely because of a marketplace that leads the way.

The cold reality is that supply and demand fundamentals seem to matter less to markets today, at least minute-to-minute and day-to-day. There is just too much money, from folks with no physical position to protect, shoving prices around. The amount of information fueling emotion and micro-logic is too fast and vast.

Over time, though, supply and demand fundamentals still drive the market, which drives each sector of the industry.

Along with murky directional ability, another glaring pitfall to this fragmented system is communication. When consumers want something different, or have a poor eating experience, their message begins a long way from the folks buying the bulls to breed to the cows that produce the carcass for future eating experiences.

Not to mention the distance in time. Figure a beef cow gestation length of 283 days. Figure a steer is 15 months old when he saunters beneath the golden arches. That’s right at two years from gate to plate.

Understanding each other

The truth is that industry sectors understand too little about one another. That’s what alliances and vertical cooperation between segments is supposed to help solve.

The good news is that, for all practical purposes, the carcass target for the greatest consumer value has remained virtually the same for at least 25 years.

But, understanding follows the bounty, or dearth, of communication. Both understanding and communication continue to elude beef industry sectors when it comes to one another.

Consider the recent consumer backlash surrounding lean finely textured beef (LFTB) this spring, which ultimately decimated more than one company, as well as a proven technology. There were as many beef producers unaware of LFTB as there were consumers.

When BEEF magazine recently asked leaders across the industry spectrum how the magazine could help producers the most – what topics it could cover that it wasn’t already – the common response was: “help them understand the workings of the different industry segments and their interdependence.”

All the respondents said fostering such an understanding is an industry necessity going forward. Thus, during the next year, we will profile each industry segment, offer a sense of its size, challenges and opportunities. Along with that, we’ll highlight important technologies that have helped deliver higher-quality beef animals and end products in a more efficient and cost-effective way.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)