From cool and wet to hot and dry, the summer of 2019 had it all.

October 8, 2019

By Becky Bolinger

Fall is here at long last and for many beef producers, the change couldn’t happen soon enough. For others, especially those still experiencing floods and those seeing worsening drought, fall could well be simply the continuation of a long and devastating summer.

While the summer of 2019 may well be one we’d like to forget, let’s look back and see how this summer ranked in terms of temperature and precipitation.

Like a doctor taking your temperature and blood pressure at your annual physical, climatologists look at temperature and precipitation anomalies as a way to assess the health of the climate over a certain time period. It doesn’t tell the whole story, but it’s a good start.

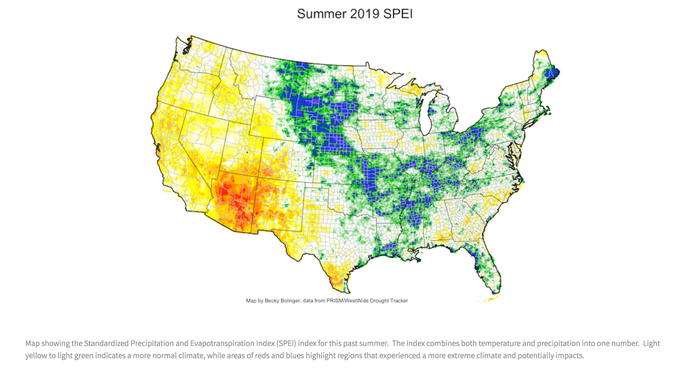

The Standardized Precipitation and Evapotranspiration Index, or SPEI (Figure 1), is a helpful index we use to combine both temperature and precipitation into one number, giving us a quick overview of conditions. Looking specifically over June-July-August (the climatological summer), this figure shows SPEI for the summer 2019 over the contiguous United States.

A general range from light yellow to white to light green would indicate a more normal climate, a range of conditions that we would typically expect in that region. Areas of reds and blues highlight regions that experienced a more extreme climate. The more extreme the climate, the harder it is for that climate to return to normal, regardless of which end of the spectrum it occurs. Extremes are hard on the land and likely mean impacts.

In the blue, we’re looking at areas that experienced a combination of cold and wet, bordering on extreme. In the red, these areas experienced a combination of hot and dry. Both cases can (and did) have negative impacts on vegetation.

In the southwest and around the Four Corners region, where people are still recovering from the 2018 drought, vegetation quickly became stressed and drought returned on the U.S. Drought Monitor map. A swath of blue over the central U.S. coincides with areas that have had issues with flooding and failed crops due to too much water.

Couldn’t catch a break

Looking at the central U.S., one might wonder why it seemed like the region couldn’t catch a break. Why wouldn’t it warm up and dry out more? Unfortunately, it’s a tough feedback loop to break.

As the sun hits the ground, the ground releases energy. When the ground is moist, it releases latent heat energy, which cools the air right above it. That latent energy is also evaporating more moisture into the atmosphere. Latent heat is limiting how warm the air temperature can get and increasing the likelihood for more precipitation.

The opposite occurs when the ground is dry. A dry ground will release more sensible heat energy, which acts to further warm the air right above it and limits the generation of precipitation. Obviously, these feedback loops don’t last forever, but a persistent pattern can be more difficult to shift away from.

Bolinger is the Colorado assistant state climatologist. She is based at Colorado State University and is a frequent contributor to Livestock Wx, the U.S. Drought Monitor and tracks all things climate around Colorado. Source: Livestock Wx, which is solely responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like