Consider the no-depreciation cow-calf operation

Unlike many assets, cows actually appreciate in value for a while, and you could capture that as profit.

There's a more profitable way to run a cow operation than the "normal" model.

Specifically, you can eliminate cow depreciation, capture heifer appreciation, and create asset turnover to increase profits.

In a traditionally managed cow-calf operation, cows are kept until death, or a non-production event. Through the years, depreciation robs the owner of a considerable dose of equity, and the cow must pay her keep with profitable calves at the same time her declining value is robbing the rancher of asset value.

Further, the classic model of a cow-calf operation is that of an asset-management business: It holds great gobs of capital in the form of depreciable assets, spends varying amounts on upkeep and some inputs, and tries to overcome depreciation and create profitability by selling a product (calves). It's that depreciating, non-working capital that creates such a headwind.

Here's an alternative to the traditional cow-man's ranch: Cows are raised at home or can be bought as light heifers and then kept no longer than peak value (appreciation) at 4-5 years old. Then they are sold and younger stock takes their place. This sells a major asset (cows) before depreciation begins to rob profit from the operation. Selling cows younger also increases monetary turnover and therefore can further increase profits.

Most often, heifers are raised or bought at about 450-550 pounds. Commonly they increase in value by $1,000 or more and raise two or three calves before moving on, says Wally Olson, an Oklahoma rancher who turned this idea into a working model and now teaches it as part of his marketing schools.

Appreciate, not depreciate

The whole idea of appreciation goes over the heads of most people, Olson says.

"Most people just will not, or cannot, hear the word appreciation," he says."But a heifer usually appreciates from a weaned calf going forward to about four or five years, if she becomes a producing cow."

Take a look at any market report to see this, or better yet combine market reports with real prices from the country. However, remember that from May through August the replacement cow markets are pretty dead, Olson warns.

With that in mind, in the June 7 Ag Marketing Service report from Oklahoma National Stockyards, medium- to large-frame heifers in the 450-pound range sold for $157 to $162 per cwt. therefore $707-$729. Bred cows listed as 2 to 4 years old were bringing 1,210-1,360. (Remember, this is not country prices and it is in the poor pricing season for cows.) Bred cows listed as 7 to 8 years old were bringing $985-1,075.

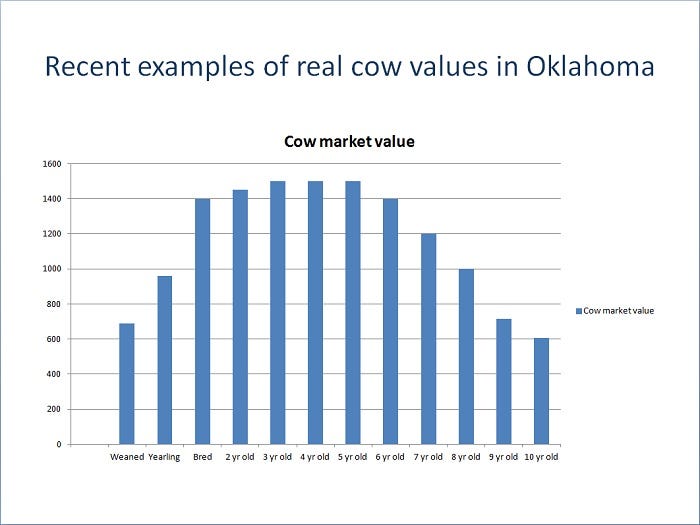

Notice in the chart labeled "Recent example of real cow values in Oklahoma" that peak value is reached at 3 to 5 years old. This is typical year in and year out.

A key practice to make this no-depreciation cow herd produce is you keep pretty much all your heifers every year, Olson says. Also, don't spend a bunch of money on heifer development. Just put a bull with them. The ones that get bred will be cows. They will also be the easy keepers. The others will be sold as feeder heifers.

"This is the ultimate selection, because you're only selecting for the heifers with high reproductivity," Olson adds.

If your cost to carry livestock (cost of gain) is kept low enough, you should still have a profit in the feeder heifers. Those sold will be replaced with more light heifers and the process starts over again.

"I tell people run the ranch on steer calves and build wealth on your heifers," Olson says. He says heifers are an ideal asset because they will appreciate much more than a steer can appreciate by gain alone.

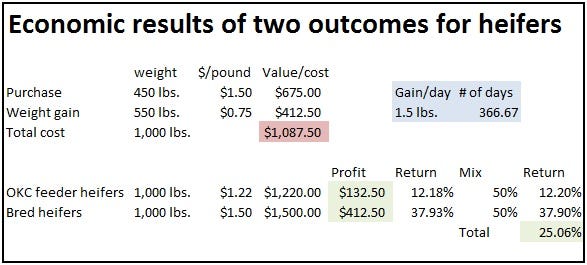

This chart helps explain how keeping a large bunch of heifers and exposing all to the bulls can potentially produce a handsome profit.

Budget the possibilities

If you look at the small chart with this story, you'll see a significant difference in expected value from the two types of heifers based on prices just a few weeks ago.

The original purchase price at a 450-pound weight suggests a $675 value. Keeping them to 1,000 pounds for 550 pounds of gain cost about $1 per day or 75 cents per pound of gain. Olson always calculates a per-day cost to keep animals because he can better apply it to cows as well as gaining cattle such as steers or heifers and because the amount of gain will vary.

Note in his budget the 1,000-pound bred heifers were worth about $1.50 per pound, or $1,500, and returned almost 38% over their cost of $1,087.50. The 1,000-pound open heifers were worth about $1.22 per pound, or $1,220, and returned 12% over their total cost. Olson used a 50% conception rate because that's been a fair average for his system.

This budget suggests a 25% gain on the whole lot. Cash in hand will depend on what you decide to sell or keep.

Further, if you re-run these calculations with prices from the first week of June you'll see a the higher purchase price of the heifers, had they been purchased at about $1.65 per hundredweight rather than raised, would potentially eat up most of the profit for them. That should emphasize another of Olson's admonitions to keep daily updates on your total livestock inventory and look for opportunities to profit from them.

This graphic uses fairly recent data from Oklahoma sale barns and country sales to show how heifers appreciate as they become cows, then depreciate as they become old cows.

Here are some keys to make this method work

Besides understanding the truth about depreciation and appreciation of cows, there are a few other paradigms you might want to change.

If you buy cows, do it in the off season when prices are lower, when everybody is baling hay.

Must know your cost to keep livestock, preferably on a daily basis. You really don't know rate of gain, therefore the cost of gain. Knowing cost to keep gives you a better measuring stick across livestock classes.

Know the tax consequences (an expense) of your actions. For example, profits from selling market animals are ordinary income. Under the right conditions, selling breeding stock may result in capital gains only, which is at a lower rate.

Be flexible. If you are willing to change your processes at times and to run things as much as possible contrary to everyone else you can make more money.

Keeping your cost structure low is a huge part of this equation. Olson says, "I think you should be able to run a heifer for $1 per day."

You need to know your inventory and value at all times so you can make decisions when opportunities present themselves.

Here's how younger cows generate higher income

Here's a simplified example how changing from a traditionally managed herd with the oldest cows about 10 years old generates less income versus a no-depreciation cow herd as Wally Olson suggests and has operated.

In this case, we'll suppose a 1,000-cow herd and for simplicity we will include no culling or death loss. We're also making calculations with a 100% weaned calf crop and 100% conception, also for simplicity. We will say we're selling all cows by 5 years of age and so will need a 20% replacement rate.

We will use the cow and heifer prices from the chart labeled "Recent examples of real cow values in Oklahoma." That would include bred heifers at $1,400, 500-pound heifer calves at $690, 5-year-old cows at $1,500, and 10-year-old cows at $605.

Remember we're just looking at values rather than accurate budgets, and especially at appreciation versus depreciation.

The first choice the two ranches would make is keeping heifers to breed them or selling them as calves. Keeping 200 heifers and breeding them, once bred, would yield a value of $280,000. Selling those heifers at 500 pounds would gross $138,000. The difference in value, therefore the appreciation you could capture, would be $142,000.

The second choice we need to examine is whether to sell older, depreciated cows, or 5-year-old cows in their prime. Again, for simplicity, we're going to compare things as similarly as possible, so we'll measure the value of selling 200 cull cows against the value of selling 200 prime-aged cows.

Using our values above, the 200 5-year-old cows would bring roughly $300,000. The 200 10-year-old cows would bring $121,000. That's a difference in value, technically a loss to depreciation, of $179,000.

In reality, you would sell fewer cull cows each year for less income, when compared with the 200 prime-aged cows. You would also have fewer bred heifers because not all will get pregnant, yet you still would add young, bred cows of higher appreciated value to your herd, then have the option to capture than appreciation along the way by selling before they drop in value (depreciate).

Also, for anyone really picking apart these ideas, we note in this example you would actually have a smaller calf crop to sell each year by roughly 10% or more, because you're increasing the percentage of non-breeding females in your herd. On the flip side of that equation, the older cows are logging real depreciation that deflates the value of their calves every year they stay on the ranch.

Learn more from Olson's website: olsonranchllc.com.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like