Ranching for results, not regs

Thinking differently has helped this group of Western ranchers improve native rangelands for the benefit of both cattle and wildlife.

February 27, 2019

By Dan Hottle

Sometimes it’s a challenge to look at what you do every day, and what the generations before you have done every day, from a different perspective.

But sometimes, oftentimes in fact, doing just that can lead to remarkable results. Just ask Agee Smith.

Smith is part of a group of Nevada ranchers who started thinking differently 23 years ago — well before recent federal land management agency mandates to improve the health of sagebrush country. This included using holistic resource management to balance livestock grazing with increasing native plants and wildlife habitat.

Now, Smith says his operation depends on it.

Smith is the fifth generation in his family’s line to run the Cottonwood Guest Ranch, a cow-calf and guest ranch recreational operation located in Nevada’s remote northeastern corner, in the shadow of the rugged Jarbidge Mountains.

This year marks the 23nd anniversary that he and a few of his closest ranching neighbors – known as the Shoesole Group – have used this innovative style of land management to guide natural resource conservation on three ranches encompassing more than 200,000 acres.

Landscape challenges

The Shoesole Group’s landscape is divided across several thousands of acres of Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Forest Service (USFS) federal allotments in addition to each ranch’s private property. In spite of tightening federal regulatory controls under which they operate – especially those concerning sagebrush conservation – members of the group take pride in the level of conservation success they’ve managed to achieve.

“In the early days of working Cottonwood as a young man and starting to see what could be achieved on the land but not quite being able to attain it, I began to wonder if I was in a business that was progressively becoming bad for the environment,” said Smith, looking over his privately-owned 1,200 acres of prime cattle grazing lowlands alongside Cottonwood Creek.

“Though I don’t think it was ever intentional by any landowners, you never had to look very far to find land that is suffering from overgrazing,” Smith said. “At the time our riparians down along the creek were in bad shape, fishing was getting even worse, and we were limited in areas where we allowed our cattle to graze during the spring and summer months.”

Then, just over a couple decades ago, Smith and neighboring ranchers Steven and Robin Boies of Boies Ranch were introduced to South African ecologist Allan Savory and the practice of holistic resource management (HRM), which is based on the principle that humans, their economies and the environment are inextricably linked.

However, shifting ranch management practice for Smith meant that the traditional regulated way of running cattle on Cottonwood would have to change.

Case in point: The Smiths and their daughter McKenzie and her husband Jason Molsbee no longer manage yearling cattle, a long-standing Cottonwood practice, due to the effects of the drought. Today they make proactive decisions about when and where to graze their cattle throughout the year that most closely mimics Mother Nature’s natural tendencies.

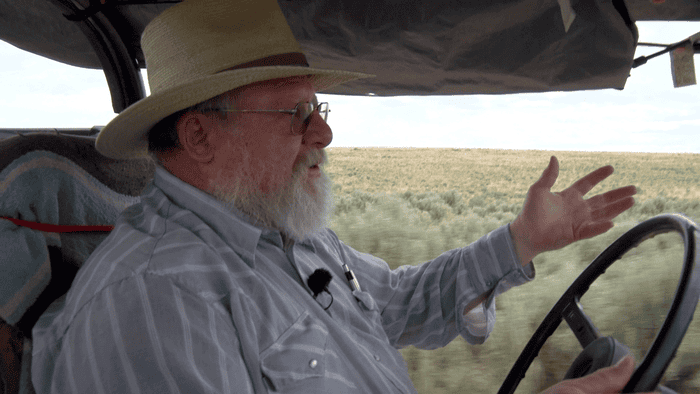

Agee Smith of Cottonwood Ranch

In other words, rather than asking, “What will happen to our cattle or the wildlife on our land if we change how things have been done here for the past 100 years?” or “How much will it cost us to change management styles?” Smith now asks himself a more simplistic end-state question: “What kinds of diverse plants and animals do we want on Cottonwood alongside our cattle that future generations of our family can enjoy and prosper from?” and then they manage for that goal.

“I thought I knew everything about this land, but … later with my own progressive education and the formal education my kids were bringing back to the ranch, I realized I knew nothing,” he said. “Just things like changing the grazing regime on our pastures to every other year, rotating our cattle, allowing for rest periods on lands that used to be overgrazed and putting riders with our cows to keep them moving, all of a sudden we had a diversity of native plants growing on our land we never even knew existed.”

No more hay

For example, nine years ago, Smith stopped growing hay on Cottonwood that that he normally used to feed his cows during the harsh winter months. They realized they could instead allow their cattle to graze early in the year on the hay pastures and strategically put them out on the range during the winter, providing a small amount of supplements to their diet and encouraging them to forage naturally.

Rotating their cattle off vital grasslands and out of fragile riparian areas also helped increase the growth of natural native grasses and forbs that made more nutritious winter ranging possible, even browsing on sagebrush.

“Sagebrush is not normally a suitable feed for cattle due to the turpines in the plant that can make a cow sick,” said Smith. “But in certain parts of the year the turpines go into the ground and the plant becomes quite nutritious.”

It’s all part of the Smiths’ holistic plan to create an animal that is more adapted to its natural environment. “A cow doesn’t want to sit in a pen all winter and eat hay,” he said. “It’s not natural. We don’t want a grass animal waiting around all day for the hay wagon to arrive. Instead, we want an animal that takes advantage of what is available across the range and still performs at a profitable level.”![Shoesole4[1].png Shoesole4[1].png](https://eu-images.contentstack.com/v3/assets/blt4175b16074920322/bltf316572b84c69b23/6485eb94d0d89b3c501adcf8/Shoesole41.png?width=985&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Here is a Cottonwood Guest Ranch riparian area in 1973. This shows the effect of uncontrolled grazing in riparian areas.

Smith feels that managing for healthy cattle and more fruitful rangelands equates to promoting a healthier native plant community, which in turn promotes a healthier wildfire regime. In 2000, the 11,000-acre Camp Creek fire burned a significant portion of Smith’s land to the bare ground, eradicating not only sagebrush, but bitter brush and other vital native grasses as well.

After the fire, crews from the Nevada Department of Wildlife and BLM drill-seeded bitterbrush and aerial seeded sagebrush.

Here is the same Cottonwood Guest Ranch riparian area in 2015. Since these areas account for only around 2% of the landscape in the arid West, protecting the water resource is vital for both cattle and wildlife.

Surprisingly, more than 25% of the bitter brush returned on its own. However, the sage-grouse that had been known to inhabit three sage grouse mating leks on his property each year had all but disappeared. In the near decade since the fire, Smith has seen sagebrush and bitter brush return in widespread dispersal in the burned area, along with a host of other natives.

For years, no grouse returned to the leks, but in 2011 three male birds returned to strut, and in 2011 there were 18 counted. Federal land management agencies are interested in the effects of soil disturbances in promoting the growth of invasive species like cheatgrass that in turn fuels more wildfires, said Smith.

“But in our case, the sagebrush around Cottonwood had grown so decadent over the years before the fire that it was losing its quality as forage and habitat for cattle or wildlife, so the fire that swept through was actually beneficial in thinning the brush and allowing a more diverse mix of native plants to come back in.

“So in some areas, land needs disturbance like wildfire and responsible grazing to thrive,” he said. “At 6,500 feet elevation, we have 12 to 14 inches of precipitation each year that helps the natives out-compete cheatgrass,” he said. So he’s in a position where proactive grazing can actually benefit native species and in turn provide resiliency against fire so that it can perform its natural function when it does happen.

“If you came in here and hammered it with cows, it’d quickly become a cheatgrass monoculture regardless of elevation," he said. "So in essence, effectively-grazed cattle can therefore become a tool for rehabilitation.”

He knows that changes don’t always come easy, but that’s just part of innovation. In fact, he admits nearly half of his private lands still require better water diversion management, and large-scale replacement of wiregrass and sedges in favor of more healthy legumes and forbs that make better cow and wildlife food and cover.

“We spend a lot more time riding our cattle than we used to, along with more pasture divisions to help monitor and maintain the health of the land,” he said. “But in another 20 years, I can envision my grandkids out here tracking our cattle with GPS systems and turning electrical grids on and off remotely to move cattle into different grazing sectors without the need for riders at all,” he said.

“When we manage for healthy lands and healthy cattle, a healthy wildlife population just naturally follows.”

Managing for sage grouse

“I was glad we were halfway down the road when the grouse situation heated up in the West because I feel we had a head start. It’s tough to watch others out there struggling with how to adapt to stricter regulations coming down the path, not knowing what their futures will look like. I feel that to be truly sustainable in our operations and for the benefit of our wildlife, we can’t afford to continue to operate in the old box way of thinking any longer.”

Smith said his fear is that new, stricter federal regulations on sagebrush conservation will inhibit ranchers’ abilities to be proactive and adaptive to their ever-changing landscapes, especially if ranchers and agencies don’t work collaboratively to solve the tough issues.

Smith’s daughter, McKenzie, who is poised to take the helm from Agee one day with her husband and two boys, understands the value of holistically managing Cottonwood for its environmentally-minded future.

“I’ve had the opportunity to grow up in this [HRM] management style with my dad for the past 20 years [now 23], and it’s all I know,” she said, “To be able to maximize our cattle production numbers, while maintaining their optimal health and simultaneously maintaining the health of our wildlife, is what keeps our family sustained and is what will provide our secure future," she said.

"When you manage for wholes and not just for your cows or for a specific species, all of a sudden you start to see diversity in the wildlife increase. So when you see sage grouse and antelope coming through your land in record numbers, you know you’re doing something right," she said.

Holistic management

Shoesole members Steve and Robin Boies (pronounced "Boyce") along with their sons Nathan and Sam, also a fifth generation ranching family, operate Boies Ranch, which lies just east of Cottonwood Ranch.

They enlisted holistic processes about 18 years ago in managing their cow-calf operation on 13,000 privately-owned acres and more than 100,000 acres of their federal allotment. Nearly all of the Boies’ property falls under the category of “Sagebrush Focal Area” (SFA), a federal designation of high-priority sagebrush habitat that was adopted in recent federal land use plan amendments for conservation purposes.

The Boieses saw the need for change when environmental pressures over cattle grazing began to mount in the 1990s.

“We knew we were in a place where we had to do something different,” said Steve. “The pressures from BLM’s management and other environmental groups were building, we were in the middle of a prolonged drought, and we were being scrutinized over the way we were grazing our cattle, specifically on our riparian areas. Something had to change.”

They voluntarily incorporated rest, change in season-of-use and dormant season cattle grazing into their management and yearly grazing schedule. These voluntary changes were adopted into their existing federal permit, which was renewed in 2011. The new permit incorporates up to 2 years rest cycle in their high-elevation mountain pastures.

“Traditionally our cattle went out to pasture April 1st and came back in October or November, then they’d be on feed in our private meadows all winter, which meant we had to keep every available acre of pastureland open for hay production,” he said. “Now we can graze some of those acres that were formerly used for hay, which saves us money and allows us more flexibility on our allotment.

“Then we regularly go back and assess if we’re trending in the right direction toward our management objectives on the landscape and come up with a new plan if we’re not. We’ve changed 100 years of livestock management, and now we’re able to observe the benefits in the health of our cattle, in our range and in the wildlife.”

At the summit of Cold Springs Mountain at an elevation of almost 8,000 feet, the Boieses also experienced the effects of the Camp Creek fire of 2000. It is Steve’s belief that collaborative holistic management and natural forces were in play in the almost unprecedented return of healthy native grasses and forbs in the burned area.

He, too, views cattle as a post-fire rehabilitative tool. Walking the once-charred landscape, Boies demonstrated his prowess for plant identification.

“We now have native Great Basin rye, squirreltail, bluebunch and spiked wheatgrass, Idaho fescue and Indian rice grass up here after the fire, a diverse mix which is a great indicator of a healthy returning plant system,” he said. “I believe this land was historically more of a grassland, and not sagebrush alone.

“So like Agee’s land, the fire came in and helped to thin the decadent sagebrush and allowed these grasses to return. Now with fire and responsible cattle grazing as a tool, we have natural plant resiliency against invasives, and our cows and the wildlife both can thrive here. If I had 100 cows out here, 10 would be on this side of the road trying to break through the heavy sagebrush to eat the sparse grass understory where the fire missed, and the other 90 would be on the burned area eating all the new diverse mix of grasses they could handle.”

Looking out across the landscape, Boies’ thoughts edged toward sentimental. “Seeing a small group of cows grazing on that hillside, where the native grasses and wildlife are now so healthy—not hundreds overgrazing, but just a smaller, managed group—producing beef, being respectful of the environment and creating prosperous families proud of the land they’ve responsibly cared for, that just makes perfect sense to me,” he said.

Regulatory trade-off

The Shoesole Group is by no means lone wolves in how they approach ranch management, as several similar collaborative groups have sprung up across the west since the mid-1990s. It is unique in that the group’s work and focus is a collaborative process of shared input when it comes to planning the yearly grazing schedule for each individual ranch.

Both Smith and Boies are also quick to give credit to the skilled facilitators they’ve used over the years and the collective efforts of their state, federal, local partners and neighbors with whom they have spent years developing trusting relationships.

In addition to the range work and monitoring efforts the group conducts with BLM and Forest Service on a regular basis, they and other neighboring ranchers also recently formed a Results-Based Grazing group that meets with those agencies quarterly to discuss implementation of the newly-amended federal land use plans in the Great Basin and to formulate best practices for responsible livestock grazing.

“We all need continuing education and help from one another, and it’s always going to continue to be a work in progress,” said Boies. “We have built a tremendous amount of trust with our partners and because of that we have an open-door policy. We know it isn’t for everyone, but it’s something that’s worked for us.”

“I wish more ranchers could see the positive benefits of things like dormant-season grazing,” he said. “We have to be aware of what the land is telling us out there, which means we can’t afford to continue to keep doing business the same old way without periodically re-evaluating our practices and adapting to changes.”

“I’m all for tradition,” added Smith. “But when we refuse to get out of our traditional boxes, it’s the land that suffers.”

“My fear is not so much in the sagebrush regulations themselves, but in how they may be interpreted by those who’d prefer to not have cattle on the landscape at all,” said Smith. “We’re out here trying to better ourselves for the land and the wildlife, so what’s hard to swallow for me is the threat of even more government regulation at the higher levels. I feel like no matter how much we accomplish, there’s always going to be a hammer looming over us from Washington to force us to meet certain standards.

"Instead, why not sit down with each other and say, ‘Mr. Landowner, we all know we want healthy rangelands, but how you get there is up to you," he said. "We’ll work together to monitor your progress, but we’re not going to be out here standing over you with a big stick. That is the kind of management that will empower those who have the desire to protect their land, but I don’t think the government has that one figured out yet.”

Boies’ sentiments mirror that of his lifetime friend and neighbor. He agrees that social, ecological and economic pressures already faced by ranchers should not be compounded with the threat of even stricter federal regulations and outside litigation.

“No two allotments are the same, and therefore they shouldn’t be managed the same,” said Boies. “All federal land permittees should be afforded the opportunity for discourse with their respective officials and be able to work with each other to evaluate an individualized plan for their futures in a positive way.

"My biggest fear is that through the Endangered Species Act or the land use plans, we’ll end up with judges and the courts making decisions about land management, and I don’t want to live and operate in that kind of environment," he said. "Just like the understory in the sagebrush, efforts to protect the ecosystem at a landscape level must start from the grassroots level with people like us,” he said.

“Managing holistically so that cattle and wildlife can exist together on a healthy landscape is the easy part. Convincing people to work together toward a common goal for the good of everyone is the hard part.”

Hottle is the public affairs officer for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service office in Reno, Nev.

You May Also Like