Why You Must Remove Net Wrap On Round Bales Before Feeding To Cattle

Large round bales are convenient and efficient, but failure to remove plastic binding before feeding can carry health risks for cows that ingest it.

October 6, 2014

Big round bales are a staple of raising cattle. You see them unrolled in the pasture, placed in feeders, chopped and windrowed by a bale processor, ground up and mixed with other feedstuffs in a total mixed ration, or placed in the field to be “bale-grazed.”

Sisal and plastic twine are the traditional standards, but in recent years, hay producers increasingly have moved to woven plastic material called net wrap. Its benefits are faster baling, reduced hay loss, and better bale integrity and water-shedding ability.

Some producers remove the twines or net wrap prior to feeding, grinding/chopping or bale grazing, while others leave them on the bales due to time constraints or inability to pull twines or wrap off frozen bales. Usually cattle eat the feed and leave the twines or wrap, which can be gathered up later. In some instances, however, cattle have become fatally impacted after ingesting excessive twine or net wrap.

NDSU research

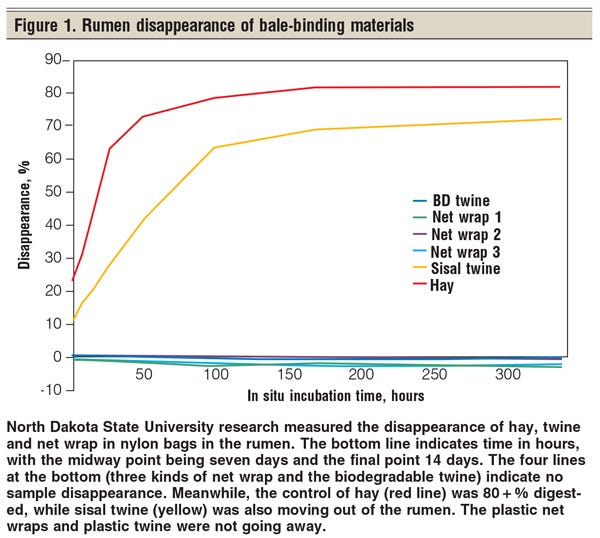

Carl Dahlen, North Dakota State University (NDSU) beef specialist, became interested in this problem after the NDSU Veterinary Diagnostic Lab in Fargo examined a case of acute bloat associated with ingestion of a large wad of net wrap. So Dahlen evaluated various materials to measure how they break down, or move through, the rumen (Figure 1).

“Many people here in the upper Great Plains use big bales. Even when processed, chopped or shredded, it’s about a 50-50 chance whether they remove the net wrap before they feed or process the hay. In feedlots, bales are commonly run through a processor. On a ranch, they’re often put through a hay-buster to spread chopped hay. In our climate, rain or snow freezes on the bales, and it’s almost impossible to get the frozen twines or net wrap off, he says.

Carl Dahlen, North Dakota State University Beef Specialist

“When people hire commercial grinders to process bales, generally by the hour, they stage the bales so they can keep feeding them into the grinding equipment. If you spend extra time getting net wrap off, it drives up costs if you haven’t staged those bales before the grinder shows up. Someone has to be out there the day before, doing that, to keep up with the grinder,” he explains.

That’s not a big challenge in the fall if moisture hasn’t frozen on the bales, or in spring after it thaws, but getting net wrap off in the winter can be a big job, he says. Some folks who bale-graze leave the net wrap on, allowing cattle to eat into the bale from the ends, to reduce the amount of hay that gets pulled out, tromped on and wasted.

Cattle often eat small pieces of net wrap or twine, but sometimes chew on large wads and just keep swallowing it, ending up with a big mass in the rumen. “We need to look at long-term implications of ingesting this material. Our study here was a short-term look at what happens to it in the rumen,” Dahlen says.

Dahlen evaluated six types of material: sisal twine, biodegradable twine, three kinds of net wrap, and hay (bromegrass, used as a control sample). Each material was cut into small pieces and 2 grams of each sample was put in bags and placed in the rumen of two forage-fed Holstein steers.

“We put the pieces into little nylon bags that wouldn’t degrade in the rumen, but rumen fluid could enter and bacterial action could happen in the bags,” Dahlen explains. After being in the rumen for varying times (four days, seven days and 14 days), the bags were removed, rinsed (to remove extra material and rumen fluid), drained, dried and then weighed.

“After 14 days in the rumen, none of the three types of net wrap or biodegradable twine samples disappeared. A large portion of the hay sample was digested and gone, and more than 70% of the sisal twine disappeared,” Dahlen says.

“Biodegradable twine breaks down in UV light, but there is no UV light in the rumen. If it’s left lying around in the environment, it breaks down over time. However, if old bales are tied with twine, it will get weak on the top surface [exposed to sunlight], but the bottom twines are still good,” he explains. Moisture doesn’t break them down.

Subscribe now to Cow-Calf Weekly to get the latest industry research and information in your inbox every Friday!

“If you’re grinding bales and not removing net wrap, it may not be a problem in a feedlot because the percentage of forage in the diet is small [not much ground hay/net wrap consumed, compared to a beef cow]. Before it would have a chance to accumulate much in the rumen, those feedlot animals are harvested,” Dahlen says.

He’s more concerned about risks for the cowherd, as net wrap can accumulate in a cow’s rumen to a point where it creates a blockage or impaction, reducing the amount of feed she can eat. The cow then loses weight.

Some ranchers have had cows waste away until they had to be humanely destroyed — and then have found net wrap in the rumen at necropsy.

“I became interested in this problem when a replacement heifer came into our diagnostic lab after she bloated and died, and was found to be full of net wrap. She and her heifer mates were eating baled cornstalks and baled hay ground up. In instances where grinding isn’t getting net wrap into very small pieces, this can be an issue. If a large piece gets into the rumen and sits on top of the fiber mass, it may block the animal’s ability to belch, and she bloats,” he says.

A second study

Dahlen conducted a second study with steers from NDSU judging classes, which were soon to be harvested. One group of steers was fed net wrap until harvest, while another group was fed net wrap until 14 days before harvest. The intent was to determine if the rumen could clear itself of the ingested net wrap.

“In our first study, we cut the net wrap into tiny pieces in bags to see if rumen microbes could break down the net wrap. The answer was no; it was still there. The second study was to see what might happen if the net wrap is floating free in the rumen while the animal burps, chews its cud, etc. The net wrap would come up with the other material, get chewed some more, and churned or pulled around during digestion. We wondered if that might clear it out of the system,” he explains.

After harvest, the cattle were opened and net wrap was found throughout the rumen, even in cattle not fed the net wrap after 14 days prior to harvest.

“That indicates the net wrap is staying in there for a while and may keep accumulating,” Dahlen says. “We also learned that cattle eat all kinds of interesting things. We’ve heard of cattle eating plastic bags and other things that block the GI tract — on the front end, which would lead to bloat (blocking ability to burp, and leading to gas buildup); or on the other end, where material can’t easily leave the rumen.”

NDSU researchers display a mass of baling material removed from the rumen of a cow.

This would create lingering effects like impaction or weight loss, because the rumen is full and the animal can’t eat much. These cattle tend to go off feed, lose weight and may have diarrhea, because only the fluid contents of the rumen get past the blockage.

A little net wrap in the rumen may not be damaging, he adds, but as the cow accumulates it over time, there can be issues with weight loss. “And some cattle get hold of a big wad and keep swallowing it down,” Dahlen says. “A person might save a cow by having a veterinarian surgically open the rumen to remove the foreign material, but you’d need a firm suspicion to warrant this invasive surgery.

Heather Smith Thomas is a Salmon, ID-based rancher and freelance writer.

You might also like:

Meet A Nebraska Couple That Practices What They Preach At Family Feedlot

Probiotics Vs. Antibiotics? Which One Wins Out For Cattle Health

4 Ways To Better Manage Your Employee Relationships

You May Also Like