How do we mitigate heat stress in feedlots?

A fluke heat event killed thousands of Kansas feedlot cattle. How do we plan for the next one?

Summers in the Midwest are hot. That’s just a fact of life that farmers and livestock producers work around every year.

But there are times when the heat and humidity can be more than normal for humans and animals alike. June 10-12, there was one such heat-load event that covered western Kansas. With daytime temperatures of more than 100 degrees F, nearly 70% humidity, low wind speeds and hot overnight temperatures, the components were there for a perfect storm of heat-stress-induced death losses in finished feedlot cattle.

A.J. Tarpoff, Kansas State University Extension beef cattle veterinarian, works with the feedlot industry across the state. He offered some thoughts on what cattle producers can do to prepare themselves for future events.

Advance monitoring

Tarpoff says many feedlots and livestock producers already monitor the weather, but there’s an online tool that can help them plan even further out.

“It’s the Heat Stress Outlook from the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center of Clay Center, Neb.,” Tarpoff says. The Heat Stress Outlook combines National Weather Service data and anticipated humidity, wind speed and solar radiation, into an animal comfort index. It’s a nationwide useful tool for cattlemen to monitor and give themselves weeks of preparation time to put mitigation strategies in place in their feedyards.

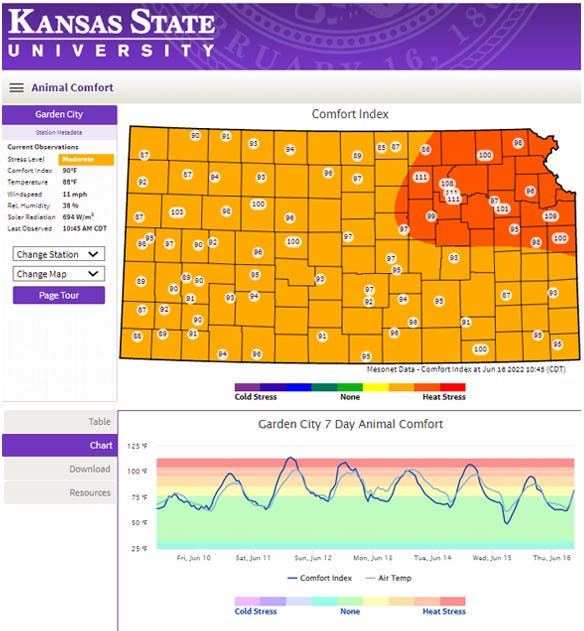

The Kansas Mesonet also has an animal comfort index targeted toward cattle, similar to the USMARC index. It’s especially helpful for tracking nighttime cooling hours.

“We can have heat-load events, but as long as we have nighttime cooling of at least six hours, our cattle can tolerate it extremely well,” Tarpoff says. “Monitoring nighttime hours and planning ahead for the days with heat-load events is critical in monitoring and timing the implementing of plans.”

Cattle

There’s a lot of variability within cattle as to their response to heat, Tarpoff says. Every animal is different, and every group of animals is different in how they’ll respond and acclimate to a change in weather.

Cattlemen can watch for a few indicators to see if their stock may have potential for trouble acclimating.

Have they fully shed their winter coats? Tarpoff says that longer hair is a thermal barrier to dissipating heat. Milder and cooler spring temperatures may have delayed that shedding.

How healthy were cattle going into the heat snap? Milder temperatures tent to mask health issues in cattle, like lung scarring from previous milder bouts with bovine respiratory disease or pneumonia. In milder weather, that’s not a big problem. But in a heat stress event, they show up in a big way. Cattle in heat stress pant for evaporative cooling, because they can’t sweat very well, Tarpoff says. If you have an issue with the animal’s respiratory tract, it’s going to show up in a heat event.

What’s your cattle breeding? Kansas is the melting pot of the entire U.S. in bringing in cattle for feeding, and usually it works well because of our drier, windier climate where they can do well, Tarpoff says. So, a feedyard may have a mix of cattle with more bos indicus, or Brahman, influence, which are bred to handle heat more; and those with more bos taurus — or, say, a British breed like Angus — which can tolerate more cold.

Immediate response

So, we’ve monitored the incoming weather, and we know what cattle we have out in the pens. Our next steps are implementing our heat stress mitigation strategies, Tarpoff says.

“It’s all hands on deck, and my hat’s off to the employees and feedlot managers out there — because when these happen, they are out in it and helping those animals any way they can,” Tarpoff says:

Water. Bringing in additional water tanks to increase capacity for the pen to drink is critical. Tarpoff says those animals need dramatically more water to cool themselves, and help with evaporative cooling. Having more water tanks also reduces crowding.

Pen floor. Feedlot pens can be huge accumulators of solar energy. Just bringing in straw to cover a pen floor to reflect sunlight can drop that pen floor temperature by about 25 degrees, Tarpoff says. That’s a huge comfort to the animals.

Sprinklers. Some operations have sprinklers set up for pens. These large water drops aren’t so much used to cool off cattle, but rather applied overnight or in the predawn hours to cool down the trapped heat on the pen floor. That can help cool the pen before the next day’s heat load.

Feeding. Feedlots don’t like to change schedules and rations on pens, but they can help somewhat to help cattle battle heat. Tarpoff says they will often change the feeding times to the early evening hours, so that when that rumen is digesting the feed and producing heat, that’s happening overnight and not at the peak heat of the day. They may also change rations so that they are more readily digestible and produce less heat. The goal is to help the animal, but also not create a digestive issue when that animal comes back onto full feed.

Wind. Windbreaks in the winter are good — not so much in the summer, though. Tarpoff says it can be as simple as moving haystacks from the perimeter of the yard that are blocking the breeze, or knocking down tall weeds on fence lines. Maintaining mounds in the center of pens can help cattle, too. He says cattle climbing that 5 to 7 feet up in the air provides a different breeze current to keep them comfortable.

Shade. “It’s a phenomenal tool, but you have to have enough of it,” Tarpoff says. A rule of thumb is to have 20 square feet per animal, and that’s difficult to do in some yards. If we don’t have enough shade surface, those animals will bunch — and there goes the advantage we were going for, he says.

One thing is clear, and that’s that any death loss in the feedyard is difficult. Not just financially, but on the crews and the staff as well, he emphasizes.

“Their livelihood and their goal is the care and well-being of those animals,” Tarpoff says. “And when they succumb to these events, it is very stressful on the crews and on the management. It’s difficult all around.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)