Individual cows vary in calf-protection behavior.

June 22, 2012

Numerous studies show that selecting beef cattle for a calm temperament improves weight gain and meat quality. Over the years, however, several ranchers have reported an increase in poor mothering among their cows. Perhaps this is the result of intensive selection during the last decade for calmer, more docile cows.

Colorado State University (CSU) graduate student Cornelia Flörcke recently spent three months on a Red Angus ranch in Colorado to learn more about how different cows protect their newborn calves. Good protective behaviors will become increasingly important as wolves spread into more and more states.

Flörcke evaluated a total of 341 cow-calf pairs, with behavioral testing performed on each cow-calf pair that had a fully mobile calf within 24 hours after calving. To test how each pair responded to a potential threat, the pair was circled in a gradually tightening spiral by a strange vehicle. This movement resembled that of an approaching predator.

The gray GMC utility vehicle, which was totally different than the ranch’s white trucks, circled slowly, gradually drawing closer to the pair. A hunter’s range finder was used to measure the distance between the vehicle and the cow-calf pair at which different behaviors were observed.

Only three really poor mothers abandoned their calves; the other cows placed themselves between their calf and the vehicle upon perceiving the presence of the vehicle as a potential threat.

As the vehicle approached, 78% of the cows called their calf by vocalizing (mooing). The three really poor mothers failed to vocalize. In addition, 13% of the cows reacted to the vehicle by lowering their heads and acting aggressively.

There was also an interesting age effect, as older, more experienced cows reacted to the vehicle when it was at a greater distance than younger cows.

Hair whorls and mothering

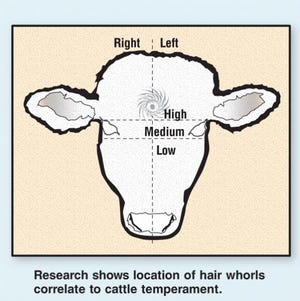

Research at CSU in 1996 found a correlation between hair whorl patterns on cattle’s foreheads and temperament. Cattle with a high spiral hair whorl above the eyes became more agitated when handled in a squeeze chute or in the auction ring (see illustration).

Research at CSU in 1996 found a correlation between hair whorl patterns on cattle’s foreheads and temperament. Cattle with a high spiral hair whorl above the eyes became more agitated when handled in a squeeze chute or in the auction ring (see illustration).

In that study, 14% of 1,500 cattle in a Colorado feedlot had high hair whorls above their eyes. In Flörcke’s recent study on mothering, only 8% of the mother cows had a high hair whorl, while 37% had a middle hair whorl and 26% had a hair whorl below the eyes. Interestingly, 11% of the cows had multiple hair whorls, 7% had abnormal flare patterns, and 11% had no hair whorl. This may be reflective of years of selection for calm temperament.

Flörcke also found that the height of the spiral hair whorl pattern and the type of hair whorl pattern were associated with cow behavior. Cows with high whorls above the eyes, or multiple hair whorls on the forehead, reacted at a greater distance by orienting themselves toward the vehicle. These animals were more vigilant.

Cows with a hair whorl above the eyes also called their calf when the vehicle was at a greater distance. There was no relationship between hair whorl type and position on cattle aggressively lowering their heads.

Ranchers often make such comments as, “she’s a wild cow but she’s given me a calf every year.” Other anecdotal observations on ranches indicate that the valuable protective traits that protect the calf may be due to vigilance, not aggression.

Cows with high hair whorls have been observed as friendly toward people. The rancher had selected his cows for a calf every year and a willingness to approach people.

More information is needed on how genetics affects mothering behavior and protectiveness. Possibly there may be two aspects of mothering behavior that may be controlled by separate genetic mechanisms. The two traits may be vigilance and differences in the strength of maternal bonding with the calf.

The beef industry definitely doesn’t want cows like the three bad mothers that abandoned their calves. These cows walked away without calling their calf or positioning themselves between the vehicle and their calf. The ideal mother cow protects her calf against predators without becoming dangerously aggressive toward people.

Temple Grandin is a professor of animal science at Colorado State University (CSU) in Fort Collins. Cornelia Flörcke is a CSU graduate research assistant.

You May Also Like