5 Trending headlines in the beef world 23

Here’s a look at 5 headlines that you don’t want to miss.

Happy Holidays! It’s been a busy week in the cattle and farming world. Let’s take a look at the drought standings and climate change, along with an attack in Montana from a big cat. Check out this week’s gathering of news headlines.

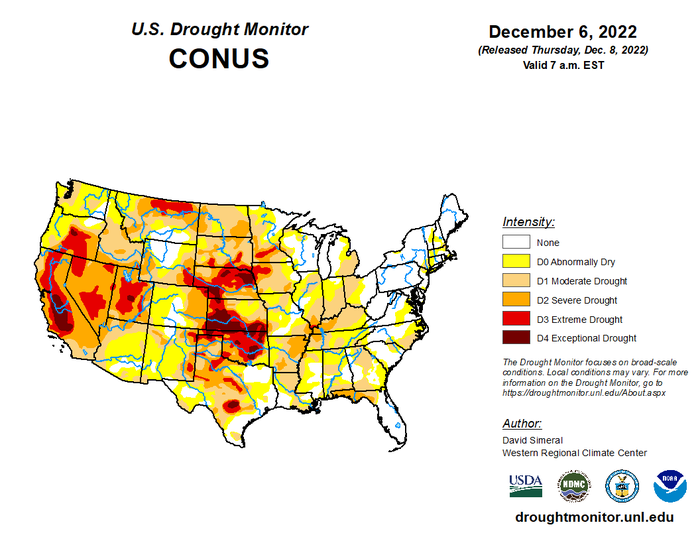

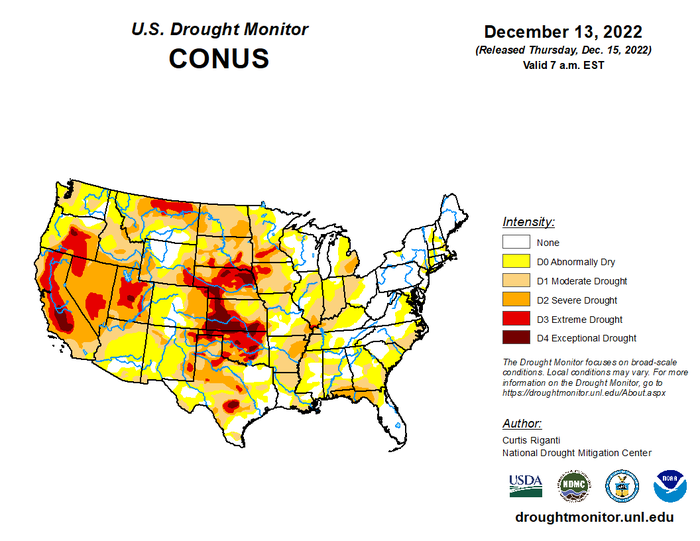

The recent drought monitor from the National Drought Mitigation Center and University of Nebraska-Lincoln show portions of Central Texas improved. Portions went from extreme drought conditions to severe drought. In the middle of Nevada, conditions went from extreme to severe. However, Oklahoma is still struggling with the majority of the state in extreme or exceptional drought.

2. Climate change is back in the news as 2022 winds down. Mostly for the “weird weather” that has plagued the United States this year.

A story from USA Today, reported this year has brought over a dozen climate disaster events with losses exceeding $1 billion, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Look for beef prices to rise in 2023 and 2024 – in part because drought in Texas is forcing ranchers to send more cows to slaughter.

"There isn't enough grass to eat, and it's become too expensive to buy feed. We’ve had a large amount of culling this year because of drought," said David Anderson, a livestock specialist at Texas A&M University.

"We're sending young female heifer cows to feed lots because we don't have the grass to keep them," he said. Cows that would normally have a calf in the next few years are instead going to slaughter.

Beef slaughter is up 13% nationwide and in the Texas region, it's up 30%.

"In the short term, that means beef will be cheaper. This year we're going to produce a record amount of beef, over 28 million pounds," said Anderson.

But long term it will mean higher prices.

Those calves that might have been born in the spring of 2023 would be ready for slaughter in about 20 months. So in the fall of 2025, there will be fewer cattle to slaughter and higher prices.

"There's going to be a shortage of beef, and prices are probably going to go up," said the USDA's Kistner-Thomas. "This could also have a compounding effect on other meat prices as people switch from beef to chicken."

Today, Texas has about 14% of the nation's beef cow herd but as the climate changes, ranchers will face growing challenges.

"These events are getting more frequent," said Anderson. The state's experiencing more frequent severe droughts. And when the rains do come, they come differently than before, in intense bursts rather than over a longer period of time.

"You may get the same total rainfall, but you're going to get it all in one afternoon," he said. "The plants are adapted for one pattern, and we're not going to have that pattern anymore."

“Horn flies are the most damaging external parasite of cattle in the U.S.,” co-author J. Derek Scasta, rangeland management specialist for UW Extension, said in a news release. The authors explain how to estimate levels of infestation and provide management recommendations, urging producers to consider economic factors and the variety of treatment options available before taking action.

“Wyoming cattle producers should consider the complexity of the situation to determine if and when treatment is appropriate,” Scasta comments. Counting individual flies might seem like an impossible (or impossibly tedious) task, but regular monitoring is the key to making informed management decisions. The authors offer guidelines on how to estimate flies per cow on a handful of animals to extrapolate the level of infestation for the entire herd. These estimates can then be used to determine whether control measures are needed. For horn flies on beef cattle, the economic threshold is estimated to be about 200 flies per cow.

4. In Richmond, Missouri, the Ray County Sheriff’s Office is warning the public about two recent attacks on cattle. One attack is attributed to an out of control dog. The other he suspects, in his words, a big cat. Ray County Sheriff Scott Childers wrote on Facebook this weekend: “This in no way is to scare anyone but to share the information to keep our community informed. Big cats have been here since I grew up in Knoxville. I have had numerous sightings but never had any contact with them.” Tarwater said, over the years, the missing bodies of young calves have been found in trees. He has also lost 13 turkeys to something. “Each one, they’d be gone. You’d only find five feathers maybe. Each one,” Tarwater said. Tarwater said it has to be something big. “A bobcat would even leave feathers. A coyote would leave feathers,” Tarwater said. But the Missouri Department of Conservation disagrees with this initial assessment of people on the ground saying that based on their investigation a dog, or possibly multiple dogs, caused the most recent attack. The Missouri Department of Conservation said young male mountain lions occasionally come through this areas, traveling in from the west. But again, their position is that no recent animal attacks have officially been attributed to big cats.

Last week, the university was awarded more than $4.7 million to help ranchers breed and raise animals who produce less methane through a USDA program aimed at expanding markets for "climate-smart" commodities. This year, the USDA has invested more than $3.1 billion in projects across the country. "What we're trying to do is look for cattle that are more sustainable by producing less methane emissions, and we're doing that through genetic evaluation," researcher and assistant professor Ann Staiger said.

Through their natural digestive process, animals produce methane, a greenhouse gas that can impact the earth's temperature and climate. Due to human-related activities such as agriculture, methane concentrations in the atmosphere have more than doubled over the past two centuries. "When we look at greenhouse emissions, the goal is to have by 2050, net zero greenhouse gas emissions," Staiger said. "When we look at agriculture, there's still a high number of green house gas emissions coming from our agricultural sector."

In 2020, agriculture accounted for about 10% of all U.S. emissions, of which livestock is a big contributor. Because of their unique digestive systems, animals such as cattle, buffalo, sheep and goats produce high levels of methane. Other animals, such as swine, horses, mules and donkeys, produce significantly less methane. In the U.S., the type of animal that produces the largest amounts of methane is beef cattle.

But, how much methane an animal produces can depend on a variety of factors, but generally, animals with lower feed intakes and those that eat high-quality feed produce less emissions. This focus of the A&M University-Kingsville project — identifying cattle that are genetically predisposed to require less feed and giving ranchers and increasing their use in breeding.

"The hope is that through genetic selection, through genetic evaluation, we can produce these cattle that are better on the environment," Staiger said.

At the university, students will have the opportunity to learn about the technology and equipment measuring methane emissions and how much cattle are eating, knowledge they can use after graduation on their own ranches, Staiger said. "It's not a matter of if cattle producers are going to do this, it's more of when they are going to have to start implementing these practices," Staiger said. "If we can have that genetic evaluation built in now, we're providing a tool they can easily incorporate into their current management practices."

Staiger said that participating cattle producers would also have the benefit of marketing their more-sustainable herds to consumers interested in environmentally-conscious food. The university is working with cattle breeding companies Brahman Country Genetics, based in Wharton County, and Leachman Cattle of Colorado, as well as Zoetis, an animal health company.

"I think actually there are a lot of ranchers who are interested in sustainability because at the most basic level, what a rancher needs to succeed is land — not just land, but land that is healthy and productive," Brahman Country Genetics co-owner Rachel Cutrer said. "We care about our grasses, our water sources and our wildlife on our ranches and we understand a changing environment is a very big issue for ranchers."

Cutrer said that changes to cattle help for efficient use of resources. "The ultimate end goal of producing beef is for food consumption," Cutrer said. "We feel that the land, the natural resources and the cattle all have to work together to present a healthy environment."

The university will measure the feed efficiency and genetic data of the Brahman Country cattle, looking to identify desirable qualities in terms of methane production. Brahman Country has costumers who buy cattle semen and embryos from all over the world, Cutrer said.

"This has a huge global potential impact," Cutrer said. "Our ranch ships cattle semen and embryos to every continent except Antarctica... if we can be leaders in producing these cattle that are more environmentally-friendly, then our customers all around the world will take these same cattle and introduce them in their own native countries."

The project aims to eventually provide financial incentives for young or underrepresented minority farmers to purchase the sperm or embryos of cattle that tested genetically to have produced low emissions and to breed and integrate this quality into their herds.

Until the genetic testing is complete, researchers won't know exactly how much the breeding program might decrease emissions, Staiger said. But research has shown the impact of past genetic selection on cattle and emissions.

One 2011 study shows a 16.3% drop in beef cattle emissions between 1977 and 2007 as producers increased meat production per animal slaughtered. "That's just based off (genetic) selection for a more feed-efficient cow," Staiger said. "Now, by adding this extra level of selection for the reduced methane production, hopefully we can meet or exceed that."

When the number of flies on an animal exceeds this threshold, the value of loss becomes larger than the cost of control. If treatment is deemed necessary, the authors recommend integrating multiple control strategies. Depending on the situation, control options might include animal rotation and habitat disruption; chemical treatments, such as backrubbers, ear tags and sprays; and breed selection. Some elevations and animals may be more susceptible to high infestation levels, researchers note. UW studies suggest that as elevation increases, horn fly numbers may drop. Certain breeds of cattle – as well as individuals within those types – may exhibit greater resistance to infestations, meaning that intentional selection may offer a viable management strategy over time.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)