No quick fix to slaughter crunch

Livestock Outlook: Beef cow slaughter data hint that cow-calf producers in some parts of the country may be trimming herds in response to COVID-19.

June 18, 2020

A colleague recently shared with me a YouTube video on “How to butcher beef.” An astonishing 6.13 million people and counting have watched this video since it was posted last September. In May, the University of Illinois issued a news release headlined, “At-home animal slaughter involves risk, challenges.”

USDA’s National Ag Statistics Service provides data on animals slaughtered on farms primarily for home consumption in its Livestock Slaughter Annual Summary report. This excludes custom slaughter for farmers at commercial establishments but includes mobile slaughtering on farms.

In 2019, on-farm cattle slaughter totaled 100,600 head. That was the highest level since 2013 but was still only 0.3% of the total annual cattle harvest. While every bit helps, on-farm slaughter can’t solve a capacity crunch. That takes volume.

Economies of scale get a lot of discussion. In meat processing, the ability to spread costs (such as labor, overhead, transportation, etc.) over a larger throughput allows larger facilities to produce higher volumes at lower costs per animal than smaller facilities can. But with the current large backlog of cattle, a lot can be said about the sheer abilities of scale.

I’ve heard many instances of locker facilities going from a few weeks out to get an animal processed to literally being booked through spring 2021. And even if smaller-scale packers had room, there aren’t enough days or plants to meet this country’s demand and the international demand for meat. Consumers worldwide rely on the U.S. for a safe, reliable, high-quality, price-competitive supply of meat.

COVID-19 impacts vary widely

Looking at different types of slaughter, different classes of cattle and regional slaughter volumes reveals significant differences in the relative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. On the surface, shocks to packing plant capacity appeared generalizable. But most concern was steer and heifer slaughter capabilities as opposed to total cattle slaughter, which also includes dairy cows, beef cows and bulls. Steer and heifer slaughter averaged 79% of total cattle slaughter in 2019. Steers and heifers are fed cattle, the primary output of the U.S. beef cattle supply chain.

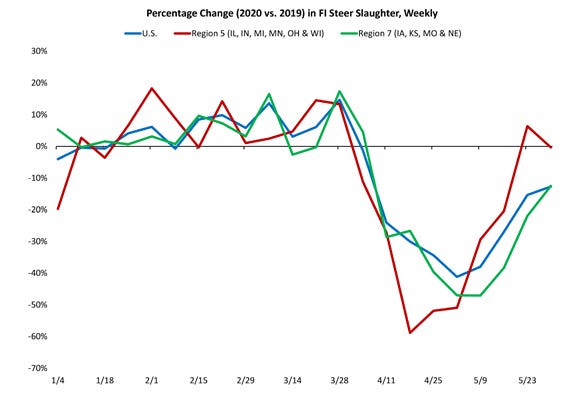

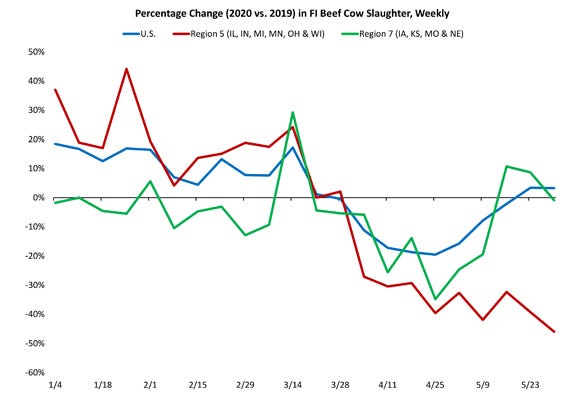

Source for charts: USDA Market News Service, U.S. Federally Inspected Slaughter by Region (SJ_LS713) reports

Slaughter cows and bulls are important residual outputs of dairy enterprises and beef-breeding herds. The marketing windows for cows and bulls can be wider because greatly extending days on feed is usually not as detrimental to carcass quality and cost of gain as can be the case for steers and heifers.

Over the 10 weeks beginning the week ending April 11, U.S. federally inspected (FI) steer and heifer slaughter averaged 22% lower than the same period last year, a decrease of over 1.1 million head, which is over two weeks of typical fed cattle slaughter at this time of year.

Iowa has roughly 9% of the total U.S. cattle on feed inventory suggesting that the state has a backlog of about 100,000 head of cattle. But this doesn’t fully capture the whole story. Those numbers were of national slaughter. Much discussion centered around national aggregate FI slaughter volumes, plant-specific closures, reopenings and slowdown announcements. State and regional impacts are equally important.

The majority of Iowa fed cattle are slaughtered in either Nebraska or east of the Mississippi River in Illinois or Wisconsin. These regions have been some of the hardest hit by the reduction in beef packing capacity. Of most interest is USDA reported Region 5 (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin) and Region 7 (Iowa, Kansas, Missouri and Nebraska).

For the week ending May 2, the worst week of slaughter reduction nationally, regions 5 and 7 steer slaughter was down 51% and 47%, respectively, compared to the same week in 2019. Region 7 heifer slaughter was down 50%. For comparison, national steer and heifer slaughter was down 41% that same week. Heifer slaughter hasn’t been reported for Region 5 since week ending Dec. 30, 2017, due to confidentiality restrictions.

Reduction in fed cattle slaughter in regions 5 and 7 has been greater than the reduction nationally by an average of 4 percentage points over the last eight reported weeks. This suggests the Midwest could have a disproportionately large supply of market-ready cattle.

Cow herd trends complicated

Looking at the national data may be masking contractionary trends in the beef cow herd. Liquidation may be in play, even if heifer slaughter is below a year ago. For the week ending April 4 to the week ending May 16, 13% fewer beef cows nationally were slaughtered compared to the same period in 2019. Several reasons could have driven this including:

reduced cow plant packing capacity

some cull cow plants or hybrid plants shifting to focus on slaughtering of steers and heifers

producers deciding to hold cows to wait for cull cow prices to recover from their COVID-19 plunge

Over this period, Region 4 (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North and South Carolina, and Tennessee) had a 14% increase in beef cow slaughter, and Region 6 (Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas) had no change compared to a year ago. Region 8 (Colorado, Montana, North and South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming) was down 25%. In Region 5, beef cow slaughter was down the most, on a percentage basis, across all regions at 33% year over year, while Region 7 was down 16%.

For the following two weeks, national beef cow slaughter averaged up 3% from the same weeks in 2019. Region 4 was up 15%, Region 6 up 17%, Region 7 up 4%, Region 5 down 43%, and Region 8 down 12%. Region 9 (Arizona, California, Hawaii and Nevada) was up a whopping 80% when being down on average 1% for the previous seven weeks.

Only two weeks of data is too soon to make any definitive conclusions. Still, suppose beef cow slaughter continues to run higher than last year in some regions and nationally. In response to the diminished outlook for cattle prices, cow-calf producers could be culling younger cows that could have potentially gone on to raise calves, in addition to culling cows that are aging out of herds. This would have an effect on the nation's beef cow herd — fewer cows, fewer calves, less beef produced. Or this could just be a return to normal culling and slaughter levels as cow plant operational capacities have improved.

Economic incentives remain strong for the non-fed beef market and should encourage movement of slaughter cows if producers are motivated. Culling decisions in part reflect cow productive life cycles, but they are also affected by slaughter cow prices, feed availability, the profit outlook of producing calves and cash-flow considerations.

Watch revisions

The USDA Market News Estimated Daily Livestock Slaughter under Federal Inspection (SJ_LS710) report, provides an estimated national daily and week-to-date figure that is subject to revision. More revisions have occurred in the current environment than in the past, and to accurately monitor slaughter levels, one needs to be vigilant about incorporating revisions.

The USDA Market News Actual Slaughter Under Federal Inspection (SJ_LS711) report is released with a two-week lag. This report is based on official Food Safety and Inspection Service slaughter data. The USDA Market News U.S. Federally Inspected Slaughter by Region (SJ_LS713) report, also lagged two weeks, shows a breakout of all classes of slaughtered cattle by region.

Can non-federally inspected plants pick up the slack?

All meat produced for retail sale in the U.S. must come from animals slaughtered and processed under continuous inspection. Every animal is inspected before and after slaughter. Inspection includes examination, checking or testing of a carcass and/or meat against established government standards and involves checking the facility for cleanliness, health of animals, or parts of animals and quality of the meat produced.

Meat from animals slaughtered and processed under federal inspection (FI) can be sold interstate. Meat from animals slaughtered and processed under state inspection only— non-federal inspection (NFI)—is limited to intrastate commerce, unless the state and facility participates in the Cooperative Interstate Shipment Program. Talmadge-Aiken plants are FI slaughter establishments in which USDA is responsible for inspection, but state employees do the inspections.

Custom-exempt are a classification of slaughter plants that do not sell meat but operate on a custom basis only. The animals and meat are not inspected, but the facilities must meet health standards. Custom exempt is considered NFI and the slaughter volume is included in NFI totals.

Total commercial U.S. cattle slaughter for 2019 was 33.555 million head of which 485,900 head, or 1.4%, was NFI. The first three months of 2020 were similar. In April 2020 total commercial cattle slaughter was 2.239 million head of which 50,000 head, or 2.2%, was NFI. This was the highest percentage of NFI cattle slaughter since December 1997. This suggest efforts to find alternative outlets outside the conventional or typical processing channels for market-ready cattle have been fruitful.

However, we must realize an upper bound exists on NFI slaughter. The highest monthly NFI cattle slaughter since 2000 was 61,400 head and since 1990 was 86,600 head. These plants, pre-COVID-19, during the pandemic, and as will be the case well after COVID-19 fades, face many constraints such as physical infrastructure, equipment, cooler space and availability of skilled labor.

Schulz is the ISU Extension livestock marketing economist. Send email to [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)