Welcome to Health Ranch, where you can find information and resources to help you put the health and well-being of your cattle at the top of the priority list.

Identify and control the most economically important parasite in today’s beef herds

November 1, 2020

Sponsored Content

Ostertagia ostertagi — also known as the brown stomach worm — is the most economically important parasite in cattle. An infection can reduce weight gain by up to 20 pounds per calf, and is estimated to cost the U.S. cattle industry $2 billion per year due to lost productivity and increased operating expenses.1

How do herds become infected?

Unlike other stomach worms, the brown stomach worm penetrates the lining of the abomasum, then has the unique ability to become dormant, allowing the next generation to survive during weather that’s too cold or too hot. When conditions improve, the larvae can emerge all at once, causing severe inflammation and irritation, reduced feed intake and sometimes even death.

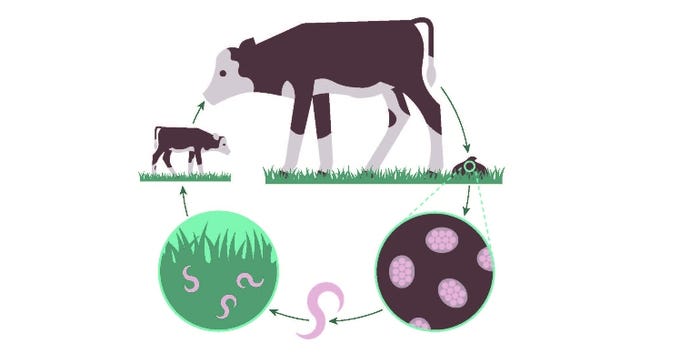

The brown stomach worm life cycle:

Adult parasites lay eggs in the gastrointestinal tract of cattle.

Eggs are expelled from the cattle through feces.

Eggs hatch and develop into infected larvae.

Infected larvae crawl onto the grass that cattle graze on.

Larvae are ingested by cattle.

Stocking density and weather conditions can influence the likelihood of this cycle continuing, and consequently the number of parasites present at any given time.

“Parasites like the brown stomach worm place themselves in the best position to be ingested by cattle,” explained Stephen Foulke, DVM, DABVP, Boehringer Ingelheim. “They try to stay at the top of the grass blades during the day, and migrate back down to ground level overnight.”

Note, overgrazing pastures forces cattle to graze closer to the fecal pat, placing them at greater risk of being infected. Studies have found that the climate at the base of the grass is very favorable for larval survival, and can harbor large numbers of parasite larvae. Some larvae migrated as far as 15 centimeters down into the soil, allowing them to survive adverse weather conditions, and then return to the surface for ingestion.1

Rainfall and other adverse weather conditions allow larvae to be more easily transported away from the fecal matter. In fact, a minimal amount of water can transport larvae up to 35 inches away from their original location.1

An effective deworming program will start by eliminating the adult worms in the system, rendering them unable to shed eggs into the environment and establish a cycle of pasture reinfestation.

Managing the brown stomach worm

“Producers often ask about the best deworming protocols, but unfortunately, that answer is different for every farm,” said Dr. Foulke. The way you’re going to deworm a cow-calf herd in the Midwest is going to be very different than deworming a stocker operation in Florida.

However, regardless of operation type, it’s always important to ensure the deworming product is stored correctly and the dose you’re administering is accurate for the weight of animal you’re treating.

A common practice is to dose dewormers according to the average weight of the herd. While convenient, this can over- or under-dose a significant number of the cattle, and diminish the effectiveness of the drug. Investing in a scale for your herd can provide more accurate dosing while reducing product waste.

No two herds or operations are the same, and neither are their parasite burdens.

A local veterinarian can help you determine the parasite load in your animals and on your pasture throughout the year, as well as adapt control methods to effectively manage parasites in all weather conditions.

Reference:

1 Stromberg BE, Gasbarre LC. Gastrointestinal nematode control programs with an emphasis on cattle. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract (2006);22(3)543–565.

©2020 Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc., Duluth, GA. All Rights Reserved. US-BOV-0583-2020-A

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like