5 Trending headlines in the beef world - Nov 8, 2022

Here’s a look at 5 headlines making the news this election week.

The weather in the Midwest is turning colder and a hurricane is expected in the southeast this week. One thing that hasn’t changed much is the drought. Check out these news briefs this week.

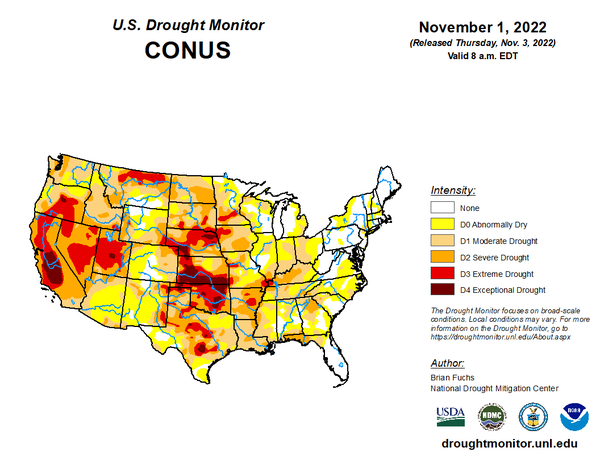

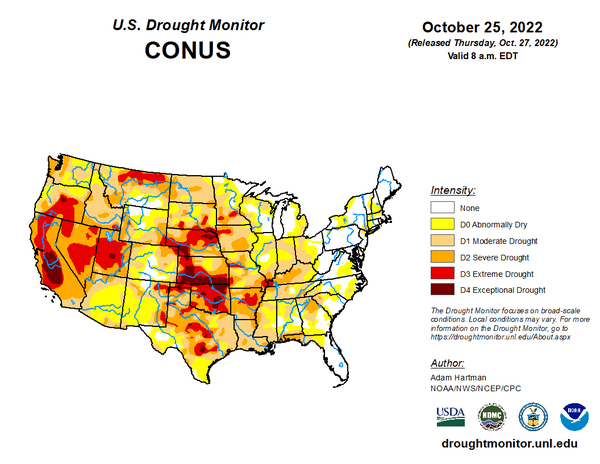

1. Let’s face it, the drought is on a lot of minds. Parts of the Midwest and southeast received some rain between Oct. 25 and Nov. 1. However, the drought remains strong or worse in the southwest.

2. And with the drought, comes water woes for ranches and farms.

Workers with the water district in Wenden, Arizona, saw something remarkable last year as they slowly lowered a camera into the drought-stricken town’s well: The water was moving.

But the aquifer which sits below the small desert town in the southwestern part of the state is not a river; it’s a massive, underground reservoir which stores water built up over thousands of years. And that water is almost always still.

Gary Saiter, a longtime resident and head of the Wenden Water Improvement District, said the water was moving because it was being pumped rapidly out of the ground by a neighboring well belonging to Al Dahra, a United Arab Emirates-based company farming alfalfa in the Southwest.

Al Dahra did not respond to multiple requests for comment on this story.

Residents and farms pull water from the same underground pools, and as the water table declines, the thing determining how long a well lasts is how deeply it was drilled.

Now frustration is growing in Arizona’s La Paz County, as shallower wells run dry amid the Southwest’s worst drought in 1,200 years. Much of the frustration is pointed at the area’s huge, foreign-owned farms growing thirsty crops like alfalfa, which ultimately get shipped to feed cattle and other livestock overseas.

Residents and local officials say lax groundwater laws give agriculture the upper hand, allowing farms to pump unlimited water as long as they own or lease the property to drill wells into. In around 80% of the state, Arizona has no laws overseeing how much water corporate megafarms are using, nor is there any way for the state to track it.Shallow, residential wells in the county started drying up in 2015, local officials say, and deeper municipal well levels have steadily declined. In Salome, local water utility owner Bill Farr told CNN his well — which supplies water to more than 200 customers, including the local schools — is “nearing the end of its useful life.”

And in Wenden, water in the town well has been plummeting. Saiter told CNN the depth-to-water — how deep below the surface the top of the water table is — has dropped from about 100 feet in the late 1950s to about 540 feet in 2022, already far beyond what an average residential well can reach. Saiter is anxious the farms’ rapid water use could push the water table too low for the town well to draw safe water from.

3. Montana ranchers seeking the culprit who killed their cattle.

Paul and Jean Loyning have lived on their ranch at the base of the Pryor Mountains for decades and say every day brings something new. Their 18,000-acre property near the Montana-Wyoming border is their livelihood.

When their neighbors called around 4:30 Monday afternoon to let them know three of their cows had been found shot dead, they were shocked.

“I didn’t understand why anybody would do something like that to an And the Loynings have no idea why someone would target their cattle. The loss of these animals will cost them at least $5,000, but that’s the least of their worries.The cows were left for dead after they had been shot.

“Killed them for no reason, looks like. Didn’t get any meat,” said Paul.

According to witnesses, a man in a Dodge Dakota drove up the dirt road Monday afternoon and shot two calves and a cow from inside his truck.

“Shoot them right out of the window with a small caliber gun, it looks like,” said Paul.

The shooter has yet to be identified and the Carbon County Sheriff’s Office said the case is currently under investigation.

4. And a look at what agroforestry can do to help cattle move from climate criminals to heroes.

But they can also be farmed in a way that can tip the scales into positive environmental impact. It is a form of agroforestry called silvopastoralism and is growing in popularity around the world.

On the Brazilian Cerrado, Bruno Junqueira de Andrade has been steadily introducing silvopastoralism to Ecofarms, the farm he took over from his father in 2015. He practices rotational gazing, with cattle given access to nutritious forage grasses, herbs, shrubs and trees. This improves their diet, while the plants boost the fertility of the soil and improve water filtration. The trees also provide shade, offering livestock a welcome respite from the heat.

There are important financial benefits, too. The combination of different plant species ensures fodder is available all year, so there is no longer any need to buy in feed. The plant diversity supports pollinators, and ranchers can also harvest other forest products such as fruit, honey and sustainable firewood.

The addition of trees and other plants can also help to neutralise emissions by increasing carbon storage.

It’s an approach that means Andrade can sell around 300 head of cattle each year through Granbeef, a sustainable Dutch meat brand, with certification by Rainforest Alliance. But a further 800 cows still go to the Minerva slaughterhouse, one of the biggest beef exporters in South America, which, he says, “don’t pay a price for sustainability yet”.

Ten thousand kilometres away in Kenya, on the foothills of Mount Elgon, cattle farming takes place on a completely different scale. Here smallholders keep just one or two cows, explains Jonathan Domarle, a senior project manager at Livelihoods Funds, which provides impact investment to support more sustainable food production. The organisation is halfway through a 10-year project to revolutionise dairy farming in the region.

Many cows aren’t fed properly, he says, especially in the dry season, when there is little more than nutrient-poor maize stalks available. As a result, cattle are often in poor health, while milk production is low.

Yet the cows are often the most profitable part of the farm, he says, thanks to a boom in milk sales across Kenya. By helping the farmers to look at the economics of their farm, Domarle and his team are helping them to meet this demand.

As in Brazil, the emphasis is on improving the quality of the fodder given to the cows, although in this case to improve milk production. By encouraging the farmers to replace some of the maize they grow with nutrient-rich fodder crops such as elephant grass and the shrub Calliandra calothyrus, farmers can double the daily milk production from each cow to seven litres, while also boosting its protein content.

The project is also about reducing carbon emissions, says Domarle, both through farming methods and improving the efficiency of the cow, with a better diet helping to cut the amount of CO2 produced per litre of milk.

“The key aim is to increase the quantity of milk that each cow produces but without asking the farmer to buy more feed from outside,” he says.

The plots are often no more than couple of hectares, but many are now surrounded by ditches that collect rainwater, their banks carpeted in lush green grasses and sweet potatoes, while trees – some planted for timber, some for fruit – also mark out the boundaries between each plot. This has led to a root system that holds the soil together and prevents erosion.

The scope of the project is huge and has so far engaged with more than 15,000 farmers. Most of the milk is consumed locally but there are alo opportunities to sell any excess to local co-operatives and milk companies such as Brookside, which is partly owned by Danone.

In the UK, Tim Downes has found another benefit of silvopastoralism: plant the right trees, he says, and cows can self-medicate.

His Shropshire farm has 150 beef and 500 dairy cows and went organic in 1998. Since then, he has worked with the Woodland Trust to introduce more trees, including willow, which is rich in salicylic acid, an active ingredient of aspirin. By grazing the trees, and eating a nutrient rich willow hay during winter, the farm’s medical bills have dropped considerably.

Downes has also planted other native trees, including sycamore and hornbeam, where the emphasis is on improving the soil and pasture. “Rye grass is the mainstay of grassland land production in temperate regions (but) it doesn't root deeply so accesses nutrients in the top of the soil,” he explains.

Different trees have different rooting zones, he continues, and bring up different minerals to the surface, allowing different forage crops to thrive. The trees also make the soil more friable, and he has found far more worms at the base of trees then in the more compacted pastures that don’t have the sylvan cover.

Downes sells much of his beef to Waitrose’s organic scheme. “We couldn’t access that market with Waitrose if we were farming intensively,” he says, while much of his milk goes to the Organic Milk Suppliers Co-operative. The way in which he runs his farm has also allowed him to access the lucrative American organic market.

5. Plus, New Zealand farmers are starting to fight back against the idea of a tax on cow burps.

Farmers across New Zealand took to the streets on their tractors Thursday to protest government plans to tax cow burps and other greenhouse gas emissions, although the rallies were smaller than many had expected.

Lobby group Groundswell New Zealand helped organize more than 50 protests in towns and cities across the country, the biggest involving a few dozen vehicles.

Last week, the government proposed a new farm levy as part of a plan to tackle climate change. The government said it would be a world first, and that farmers should be able to recoup the cost by charging more for climate-friendly products.

At the protest in Wellington, farmer Dave McCurdy said he was disappointed in the small turnout, but said most farmers were working hard on their farms during a spell of good spring weather at a particularly busy time of year.

He said farmers were good environmental stewards.

He said the proposed tax didn't take proper account of all the trees and brush he and other farmers had planted, which helped trap carbon and offset emissions. He said if the proposed tax and herd reductions went ahead, it would be ruinous to many farmers.

and dairy cattle and 26 million sheep, compared to just 5 million people — about half of all greenhouse gas emissions come from farms. Methane from burping cattle makes a particularly big contribution.

But some farmers argue the proposed tax would actually increase global greenhouse gas emissions by shifting farming to countries less efficient at making food.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)