Act Now To Minimize Cold Stress On Cattle This Winter

Good management to prepare cattle for winter and minimize weather stress can save money, and reduce the incidence of illness and animal loss.

November 4, 2014

Weather is always a factor in cattle health. Stressed animals are more vulnerable to stress-related illnesses, and cold or wet weather brings additional challenges, especially when wind is part of the equation.

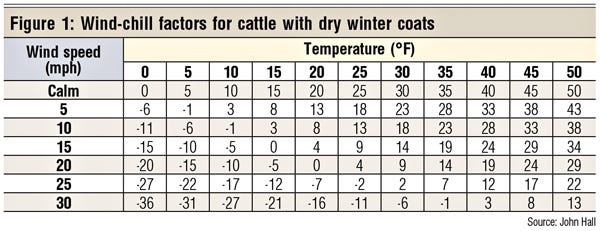

Animal care specialists say one place to start is to provide windbreaks and bedding in winter conditions. Without protection, cows can suffer frostbitten teats, bulls are vulnerable to scrotal frostbite, and calves in particular can suffer (Figure 1).

Protect young calves

Young calves are a special class, says John Hall, University of Idaho Extension beef cattle specialist. “Newborn calves are most at risk, but calves less than 2 weeks of age, and sick calves, are also at risk in severely cold weather,” he says.

Young calves can handle fairly cold temperatures once they’re dry and have that insulating effect that a dry hair coat provides, says Russ Daly, South Dakota State University Extension veterinarian. Colostrum is also important. Once the calf has nursed, it has the energy needed to keep warm.

“A calf is born with less than a day’s worth of energy in the form of brown fat to burn for body heat,” Daly says. “If the calf doesn’t get colostrum, once that brown fat is depleted, there’s no energy available for the calf to maintain or regulate body heat.”

Colostrum is high in fat, with 2-3 times the fat of regular milk. “This really makes a difference in getting the calf up and going,” Daly says. “A calf that’s nursed a full feeding of colostrum can stay warmer in cold weather.”

Hall says that lower critical temperature (LCT), which is the temperature below which the animal must burn extra energy to keep warm, is higher for calves than cows, especially if the animal is wet.

“The LCT for calves is close to 60°F — but with a little rain or snow, the LCT moves closer to 70°. As little as 0.10 in. of rain on the day the calf is born can increase calf losses by 2%-4%,” Hall says.

Young calves dry off quickly on a dry day if their mother licks them immediately after birth, Daly says. “But, sometimes, in cold weather, you have to help the process. It’s crucial to have bedding for baby calves. There’s not much body mass in a small calf, and it can chill quickly. Bedding provides some separation between the calf and frozen ground, snow, cold concrete, etc. This is important in helping calves stay warm.”

Frostbite also can be an issue for calves born in cold weather. The extremities suffer first.

Photo Gallery: Home Is Where You Hang Your Hat

At BEEF, we're proud to celebrate the ranching lifestyle. Enjoy 20+ photos from our readers that showcase their country home. Enjoy the gallery now.

“Most people who calve early calve inside. After the calf is born and dry, there’s much lower risk for frostbite, unless a calf is suffering from a debilitating condition such as scours and dehydration,” Daly says. In such cases, there’s less blood flow to extremities.

If a newborn calf suffers frozen ears, tail or feet, take care not to damage the tissues when trying to warm the calf. “If you suspect frostbite, remove the calf from cold conditions, but don’t warm ears or feet too quickly. Use warm water and towels, not hot water, and don’t rub the area too much or it may further damage the tissue. Calves with frozen feet — to the point that the feet are sloughing off — suffer a great deal of pain, and the calf should be euthanized,” Daly says.

Larger calves have more blood flow to their extremities and are more able to move out of the wind. “If shelters are used, they should be moved periodically to clean locations, with clean bedding,” Daly explains.

As calves get older, windbreaks and temporary shelter are helpful, along with good nutrition. If the calves have adequate nutrition and are in good body condition, they have more insulation against cold and enough energy to keep warm.

“We focus on protein, but energy for calves is crucial. Weaning-age calves need a high-energy diet. People here in the Northern Plains also recognize that these animals will increase their intake in response to the cold,” he says.

Hair coat is the insulation

An animal’s LCT depends on its hair coat; a heavy winter coat provides much more insulation than summer hair, and the animals won’t need extra energy to keep warm until the temperature drops below that point.

“The LCT for Idaho cows with heavy dry winter coats is about 18°F, but the LCT of wet cows is 59°F,” Hall says. If the cows aren’t receiving extra nutrition to provide the needed body heat, they burn fat and lose weight. Weight loss during late gestation will result in lower pregnancy rates the next breeding season.

Thin cows produce weaker calves, with a reduced chance of survival. In fact, Colorado State University research indicates that first-calf heifers with a body condition score of 4 or less have reduced antibody levels in their colostrum. That means their calves are more likely to become sick, Hall says.

An increase in wind chill or wet weather can dramatically increase cold stress on cows. “Research from Kansas and Iowa indicates that maintenance energy requirements of a cow increase by 1% for each degree below her LCT. For wet cows, the rule of thumb is 2% for each degree below LCT. For cows with wet coats, wind-chill temperature may easily be 20%-30% below LCT. Periods with high winds, snow or rain will dramatically increase energy requirements,” Hall explains.

Daly says providing the additional feed that cattle need in such conditions is paramount. For animals with a functional rumen — older calves and adult cattle — having adequate protein to use the energy is important. Microbes in the rumen break down the roughage in forage into usable energy, but they need protein to do this.

“With the cold weather we had last winter, stockmen were able to help cattle maintain themselves, but the prolonged cold made it challenging to feed calves enough for weight gain,” Daly says. “For mature animals, the best way to help them respond to cold stress is to feed enough energy and protein — especially as cows get into later gestation — to make sure the calf isn’t shortchanged.” If any animal is diverting all its resources to keeping warm, something else will be shortchanged.

Hall says that during normal January-February weather in Idaho, cows need an additional 3-4 lbs. of hay or 2-2½ lbs. of grain.

“Generally, you can just feed more hay to compensate for weather stress, but low-protein hay needs to be supplemented with 1-2 lbs. of protein. Cows with inadequate nutrition to stay warm will lose ½-1 lb. of weight per day,” he says.

In extremely cold or wet conditions, cows need to eat an additional 7-8 lbs. of hay or 4-5 lbs. of grain or high-energy byproducts. Otherwise, they could lose 1½-2 lbs. per day of weight, he adds.

Windbreaks and bedding can help cattle maintain body temperature without as much extra feed. They also prevent frostbitten ears or teats, or scrotal frostbite in bulls. If the teat ends suffer frostbite, they may seal over with scar tissue, preventing the newborn calf from getting colostrum. Cows should be monitored for teat damage, and possible scabbing and scarring.

“If a producer notices problems with damaged teats, the tissue damage is already there, but treatment might salvage the situation,” Daly says.

Frozen skin on the teats will heal, but may result in painful nursing during the healing process; teats may become so sore that the cow won’t let the calf nurse, and the producer must intervene. “Being aware of these possibilities is important during long stretches of really cold weather, especially if there is wind. Bedding and windbreaks can minimize the risks,” Daly says.

Bull precautions

Cold weather and/or wind chill can cause testicle damage and semen deterioration in bulls, but wind is the greatest danger, says George Perry, South Dakota State University beef reproduction specialist.

Frostbite to the testes can affect sperm production. “Spermatogenesis in a bull is 61 days. Anything that affects sperm production will take 61 days to totally clear the system and have normal cells and healthy sperm after the bull recovers,” he explains. Severe damage may take several months before the bull is fully recovered; in some cases, infertility is permanent.

For healthy sperm production, testicles must be a few degrees below body temperature. Thus, a bull lowers his testicles in hot weather, and draws them closer to the body in cold weather to keep them warm enough. Severe scarring from scrotal frostbite may interfere with raising and lowering the testicles.

“Many people don’t use enough bedding during winter to avoid frostbite in bulls. The scrotum has very little protection compared with the rest of the body, as it is bare skin with just a fine hair covering. If bulls lie on frozen ground or snow, they’re basically putting the testes on ice,” Perry says. Bedding can serve as insulation.

“The term frostbite implies minor frost damage, but tissues may also suffer severe frost damage. Stockmen need to realize the length of time it takes to recover. When the skin has healed, that’s when normal sperm production resumes, and the clock starts for the 61-day period before the healthy sperm is mature and the bull is fertile again,” Perry says.

Bulls with severe damage may not be fertile until late summer. That’s good reason to have breeding soundness exams performed on bulls each year, Perry says, before the bulls are turned out. Just because a bull was fine last year doesn’t mean he will be fertile this year, he adds.

Heather Smith Thomas is a rancher and freelance writer based in Salmon, ID.

You might also enjoy:

80 Photos Of Our Favorite Calves & Cowboys

Why The Cattle Market Is At A Critical Juncture

Producers Must Act Now To Save Their Beef Checkoff Program

Buying A New Herd Bull? Do These 4 Steps First

3 Reasons A DVM Should Head Up Our Ebola Response

4 Tips For Eliminating Weeds This Fall

Photo Tour: World's Largest Vertically Integrated Cattle Operation

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)