How much do beef imports affect the wholesale beef market?

Despite common myths, beef imports have a minor effect on U.S. beef producers.

October 22, 2015

Over the years, there has been much discussion and concern in the beef business about the effect of beef imports on the U.S. beef market. Recently, agricultural economists at the University of Nebraska Lincoln found that beef imports are a minor substitute for domestically produced beef.

We estimate that a decrease in wholesale imported beef prices would result in an increase of imported product, but at a very small percentage. That is, domestically produced beef carcasses both from fed cattle and cull cows would be replaced by imported beef; fed cattle carcasses would be replaced at a 0.09% rate and cull cow carcasses at a 0.29% rate for every 1.0% drop in import prices.

In contrast, a rise in import prices would result in a reduction of imports and an increase in the use of domestic product. Notably, cull cow carcasses were more affected than fed cattle carcasses. This is to be expected since cull cow carcasses and the majority of beef imports (carcass portions from grass-fed animals) are primarily used in the production of ground beef, and fewer numbers of cull cows are slaughtered relative to fed cattle.

So exactly what does this mean? This can best be illustrated by considering two recent events that are part of the current economic environment in the U.S.:

And higher U.S. beef prices in the last two years, which is partially attributed to short domestic supplies.

Both of these events would, in effect, increase the domestic price relative to import values, which, given the competitive nature of beef imports to wholesale carcasses, would be expected to increase. How much they increase is a factor of the price difference as well as other factors such as the current import agreements and laws binding them.

70 photos show ranchers hard at work on the farm

Readers have submitted photos of hard-working ranchers caring for their livestock and being stewards of the land. See reader favorite photos here.

Certainly this competitive relationship is like a double-edged sword, reducing demand for domestic product and relieving upward pressure in prices for producers, perhaps helping to temper an overreaction in production (understanding that higher profits certainly are preferred to lower ones), while at the same time mitigating prices to those who purchase the product.

While imports do indeed replace some domestic product, it is not a 1:1 relationship. In fact, it is a very small portion, as noted above. The current institutional arrangements, laws, agreements and trade-limiting mechanisms limit to what extent this replacement occurs.

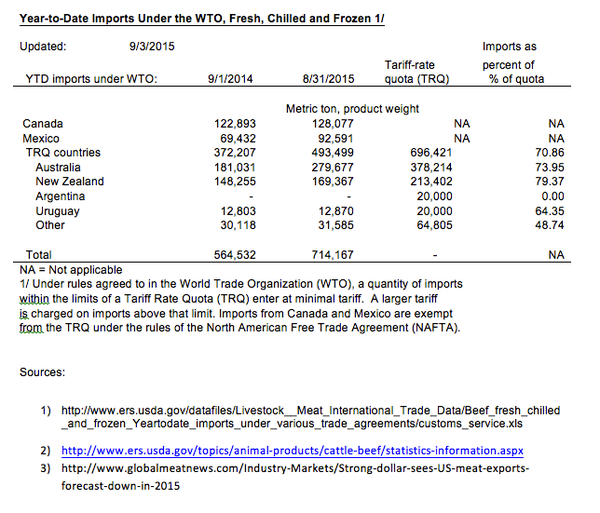

This can be seen in Figure 1. As of Sept. 1, 2014, imports totaled an annual 564,532 metric tons, which increased to 714,167 metric tons as of Aug. 31, 2015. Looking at the trade-limited countries, the percent increase as a percent of the 2015 quota amounts went from nearly 53% to just under 71%, about a 22% increase, but still nearly 30% less than the allotted amounts.

Even at the expected lower 2015 levels of exports, the U.S. is likely to export nearly 35% more beef than it imports, including Mexican and Canadian beef. The 2014 export levels were estimated to be 2.573 billion pounds and the 2015 year is estimated to be close to 2.45 billion pounds, only about 13 million pounds less.

While these issues are not addressed directly by this research, their effect on price and quantity can be used to suggest what future prices might do. With the increasing supply and a reduction in exports, given static domestic demand, it is likely that imports of beef products to the U.S. will at least stay constant if not increase. Given the passage of time, it is likely that without offsetting increases in demand or changes in exports, domestic prices will likely decline. However, knowing by how much and when is impossible to judge given the complexities of the markets.

The situation here prescribes the need for caution in making plans in any beef production operation that will permanently increase the costs of production and place increased commitments on future productivity. In conclusion, always be aware that highly profitable prices are likely to be temporary and the only sure profit is one that is in the bank.

Matthew C. Stockton is associate professor at the University of Nebraska Lincoln West Central Research & Extension Center in Hays, Kan.; Sunil P. Dhoubhadel is assistant professor in the Department of Agriculture at Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kan.; and Azzeddine M. Azzam is a professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics at the University of Nebraska Lincoln.

You might also like:

Burke Teichert: How to build better land and soil

60 stunning photos that showcase ranch work ethics

Is preconditioning still a no-brainer?

70 photos of hardworking beef producers

Ag women fire back at comments criticizing saleswoman for riding in the combine

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)