Projected lifetime returns: Bred heifers

Last month I focused on the economic cost of developing a preg-checked heifer in the fall of 2016. This month I will focus on the challenges that you and I face in projecting lifetime economic returns of adding preg-checked heifers to the herd. I believe that expanding — or not expanding — your beef cow herd and its timing is one of the more critical financial management decisions relating to your operation.

Projecting the lifetime economic returns of a preg-checked heifer is considerably more difficult than projecting the initial cost of raising a preg-checked heifer due to the long-run time frame. One of the more difficult information pieces is a projection of calf prices for the next cattle cycle.

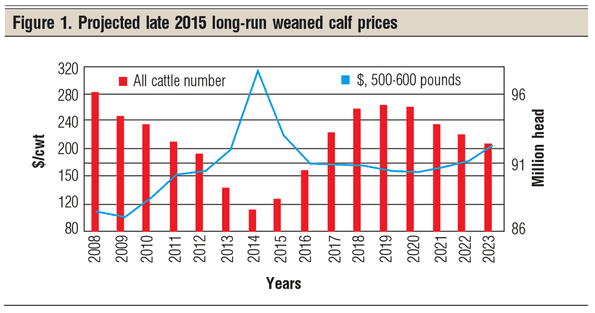

Challenge 1. The foundation for long-run calf prices has to be U.S. all-cattle numbers projected for the next seven to 10 years. In October 2015, the Food and Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) at the University of Missouri projected cattle numbers to increase slowly through 2019 and then to trend downward into 2023. In general, calf prices will move in the opposite direction of cattle numbers.

My long-run fall steer calf price projections for eastern Wyoming/western Nebraska, generated in November 2015, are summarized in Figure 1, overlaying FAPRI’s cattle number projections prepared in 2015. I did update my price projections with the actual 2015 fall weaning price and a current revised projected 2016 fall projected weaning price. Limited resources prevent me from re-estimating all these planning prices again at this time.

Higher prices

In general, if you take out 2014 and 2015 as abnormal years, 2016 through 2023 prices are projected to be considerably higher than 2008 through 2013. My suggested fall planning prices for 2016 through 2022 are in the range of $160 to $180 per cwt.

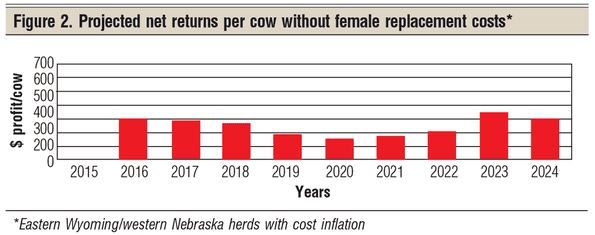

Challenge 2. The next step was to use these long-run planning prices to project the net returns from an eastern Wyoming/western Nebraska beef cow herd. I am using the same eastern Wyoming/western Nebraska study herd that I have used in other articles. In this analysis, I removed “replacement costs” from my net return projections for this study beef cow herd so I could apply these values to my heifer evaluation efforts (Figure 2).

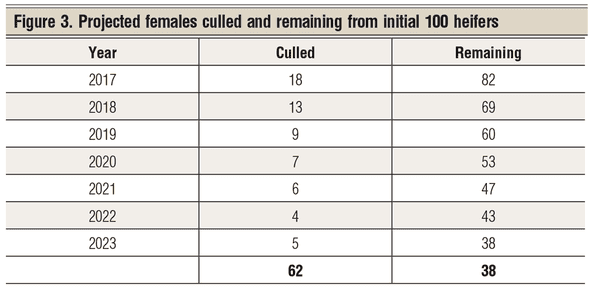

Challenge 3. A third challenge in projecting the economic value of a preg-checked heifer is the fact that not all replacement heifers will stay in the herd for the assumed seven-calf lifetime. The way I approach this challenge is to assume that I start with 100 preg-checked heifers, and then reduce the number of heifers remaining in the herd each year by culling open females until seven consecutive calf crops were produced. Then, after the seventh calf crop, all remaining females are culled (Figure 3).

Challenge 4. A fourth challenge is to put a dollar market value on open females as they are culled from this 100-female herd. In previous studies, I had assumed all open females were sold as cull cows regardless of age. After reviewing several current sale barn summaries, I decided younger open females should be sold as breeding females for considerably more money than cull cows.

I built a “breeding cow calculator” around age, color and teeth condition that attempts to duplicate current sale barn receipts for eastern Wyoming/western Nebraska breeding females. I considered that all females culled under 8 years of age had a market value above cull cow value. This supports the concept that breeding females do not depreciate much, if any, up to at least 6 to 8 years of age.

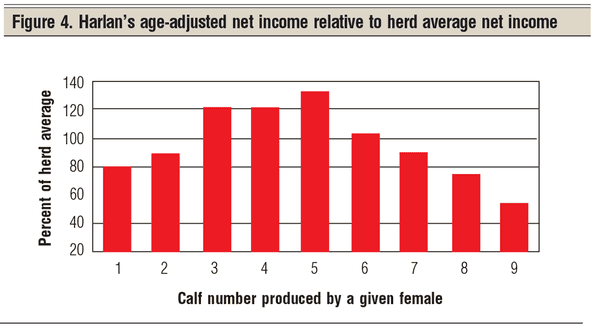

Challenge 5. A fifth challenge relates to a study that shows that net income per cow varies with the age of females in a herd. Based on some earlier work I did with CHAPS (Cow Herd Appraisal Performance System) herds in North Dakota, I concluded that females producing their third through sixth calves tend to produce above-average net incomes over the rest of the females ages in the herd, both younger and older. This is based primarily on average weaning weights by age of females. Figure 4 presents the “age adjustments” that I use in my preg-check heifer analyses.

Challenge 6. If open females are culled from the breeding herd each year, then the final economic value of 100 preg-checked heifers can be affected by the cow’s age when females are considered open. Two factors were considered: assumed weaned live calf percentage of the herd, and how the percent live calf crop varies with age of females in the herd.

Early culls

For discussion purposes, I argue that, generally, females with the tendency to be open are culled early in their lifetime; therefore, the percent live calf crop goes up with the age of females remaining in the herd. That is, up to a point in age. Again, I used CHAPS data a few years ago to draw this conclusion.

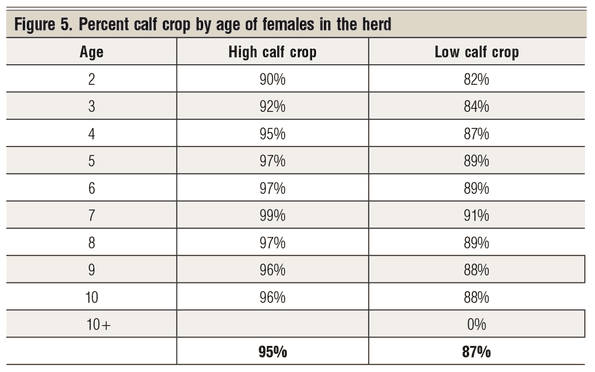

Figure 5 present the numbers I use for a herd with an 87% calf crop and the numbers I use for a herd with a 95% calf crop. I consider the 87% calf crop a typical, well-managed herd.

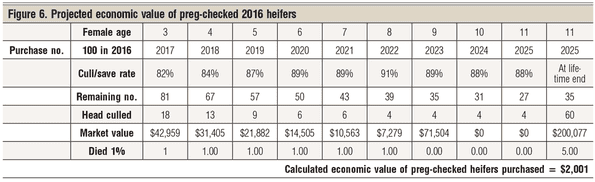

Figure 6 presents my final projection of the economic value of a preg-checked heifer for my study herd. The bottom line for each age group represents the net value of the calves sold plus the gross value of open females sold at that age level. Remember, the value of open females varies with age of open females. Each year’s total market value was discounted back to 2016. The discount factor used was 3%.

The total discounted net economic value of each female age is presented with the average accumulated total value on the right. At the end of the seventh calf crop, it is assumed that 60 head have been culled, leaving a final 35 head in the herd to be culled after the seventh calf crop is weaned. I assumed that 5 head died over the years.

The calculated total economic value of a preg-checked heifer in the fall of 2016 is projected at $2,001 per head, presented in the lower right-hand corner of Figure 6. My suggested answer, then, to the economic value of a 2016 preg-checked heifer is $2,001.

However, my $2,001 projected economic value of a 2016 preg-checked heifer is not what is of primary importance here. What is of primary importance is to get you to think about what economic and production factors impact the economic value of preg-checked heifers in your herd. I am sure you can come up with additional factors that should be taken into account, and I hope that you will share your thoughts with me.

Harlan Hughes is a North Dakota State University professor emeritus. He lives in Kuna, Idaho. Reach him at 701-238-9607 or [email protected].

You might also like:

10 photo finalists celebrating spring

Burke Teichert: How to manage your way out of a hard-calving cowherd

2016 market outlook: Here's what to expect

Getting first-calf heifers ready for the breeding

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)