Cattle Market Outlook

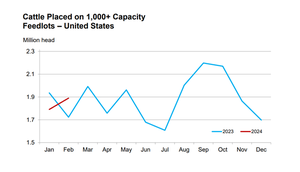

The April cattle on feed report had a few surprises for analysts.

Cattle Market Outlook

Fewer cattle but more in feedlotsFewer cattle but more in feedlots

Is it time to rebuild herds? Derrell Peel takes a look at the latest cattle on feed report.

Subscribe to Our Newsletters

BEEF Magazine is the source for beef production, management and market news.