While alternative marketing agreements (AMAs) aren’t perfect, they are an economic explanation to how a high-risk, low-margin business adapts.

June 1, 2020

COVID-19’s influence has been all-encompassing – no aspect of the beef industry has gone untouched. As such, COVID-19 has been this column’s focus in recent months. Perhaps most important, amidst the market gyrations, it’s heightened internal debate and divisiveness about the general construct of the industry and how it conducts business.

That’s brought about renewed calls for greater cash negotiation and reduced alternative marketing arrangements (AMAs) in the fed market. As a reminder, there are several key reasons why feedyards have willingly moved away from selling on a negotiated cash basis and moved toward greater utilization of AMAs, primarily formulas and forward contracts. Those include:

Taking advantage of value-added opportunities including quality grids and/or specialized programs (e.g. NHTC);

More consistent and synchronized throughput, thereby improving overall feedyard efficiency;

Avoidance of the weekly negotiation—escaping the time and hassle commitment and thus enabling heightened management administrative focus on other matters of importance;

Enhanced ability to implement disciplined risk management strategies.

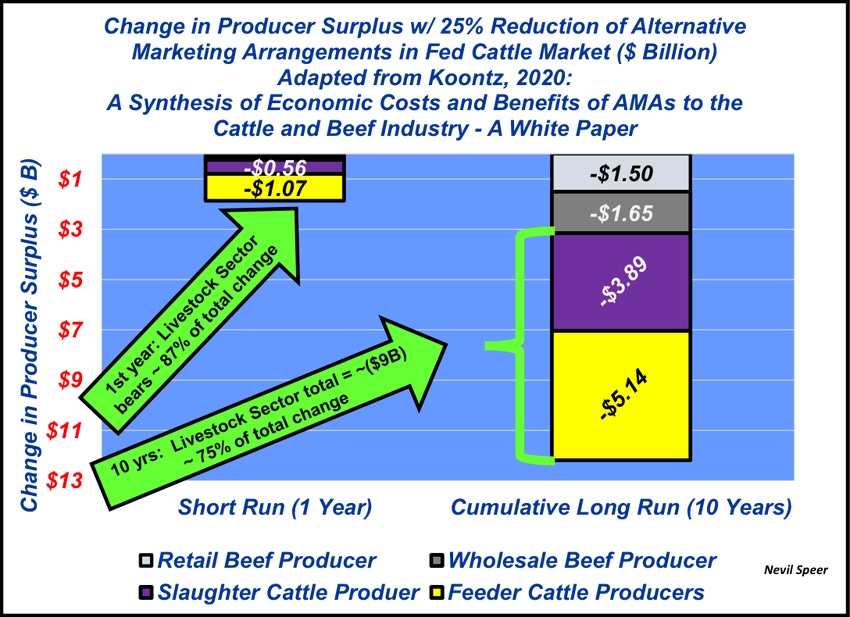

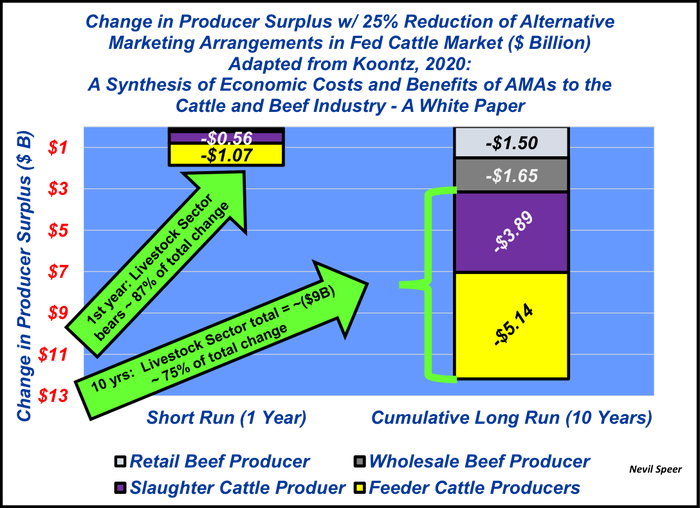

Amidst all this discussion, Stephen Koontz, ag economics professor at Colorado State University, recently compiled a white paper titled A Synthesis of Economic Costs and Benefits of AMAs to the Cattle and Beef Industry, that summarizes previous research conducted as part of the USDA GIPSA RTI Livestock and Meat Marketing Study (LMMS). Koontz emphasizes the depth and rigor of the original research in the white paper: six volumes, four teams, 30 researchers, three years of effort and inclusion of a peer review process.

Based on the research, Koontz frames proper consideration of current proposals this way:

Changes in producer and consumer surpluses can be a difficult concept to follow. These are not changes in revenues or expenditures. There’s more to it than revenue – for example costs change too – but it’s also important not to get tangled up in the subtleties.

The important thing is that the surplus changes are measures of changes in economic wellbeing. The measures are well‐accepted and are bottom-line dollar impacts. If you want to know what the economic impact of a policy will be on producers, then you are asking about producer surplus

Accordingly, this week’s illustration highlights the change in producer surplus resultant from reduced use of AMAs in the fed market. The first year’s impact would equate to roughly $1.7 billion; over 10 years the production sector absorbs an overwhelming share of the impact with a projected loss exceeding $9 billion.

Why does that occur? Ultimately the industry becomes less efficient and less responsive to consumer demand. Accordingly, Koontz points out that both feedlots and packers would be increasingly challenged to meet consumer needs – hence, new strategies would have to be developed to establish value for the beef industry in the protein market or else simply devolve back to competing predominately on a commodity basis. Because of its inherent cost structure, that would put the beef industry at a disadvantage compared to its competitors.

As noted during the past several weeks in this column, the beef industry’s evolution during the past 20 years is a significant case study in successful business transformation. The industry managed to implement more cooperation, better synchronization and increased responsiveness to consumers.

The outcome being greater competitiveness in the marketplace and evolution of new opportunities for cattle feeders, and all beef producers, along the way. And all this is a good reminder that turning back the clock won’t rectify the current challenges due to COVID. To the contrary, that’s an exercise of missing the forest for the trees.

Nevil Speer is based in Bowling Green, Ky. and serves as director of industry relations for Where Food Comes From (WFCF). The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of WFCF or its shareholders. He can be reached at [email protected]. The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of beefmagazine.com or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like