There are many reasons for the market gyrations of late. Here’s a look.

April 2, 2020

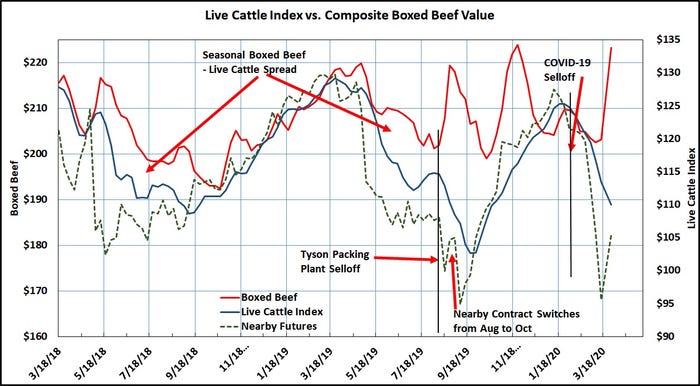

Choice wholesale beef prices spiked $45.61 per cwt higher week to week on March 20, as COVID-19 forced consumers to stay home, shifting significant beef demand away from the food service sector to retail grocery. Even though prices softened since then, Choice boxed beef cutout value March 30 was still 11% higher than a year earlier.

At the same time, plummeting cash prices for calves, feeder cattle and fed cattle that had to be marketed meant catastrophic losses for some producers, if the cattle weren’t hedged or forward-priced ahead of the COVID-19 panic.

There are many reasons for the seeming disconnect between beef prices and cattle prices, but these are primary ones, in my opinion.

Packer capacity

There is far less processing capacity today than 10 years ago. Extraordinary losses in the packing sector, as widespread drought forced massive national cowherd liquidation, forced smaller regional packing plants to close. As the cowherd expanded, reduced packing capacity gave more pricing power to the packing industry.

Beef supply

There are a tremendous number of cattle in the supply chain. Besides cowherd expansion in recent years, some ranchers are liquidating herds to generate cash after three consecutive years of losses exceeding $150 per head per year. Commercial beef production is projected to be record large this year at 27.7 billion pounds. Pork and poultry production will also be record large.

Feedlot marketing dynamics

A small number of cattle are sold to packers via cash negotiation each week—about 20% on average. The rest are sold via a formula based on the small number of animals sold on the cash market. This means packers need to negotiate with fewer sellers and gives them even more pricing power.

Futures market dynamics

Some feedlots hedge at least a portion of their cattle using Live Cattle futures. Others rely on time and seasonality, assuming it will all average out.

All hedgers in Live Cattle futures are sellers. The futures market works because speculators take the long position opposite of sellers. The problem is the lack of natural longs—producers and businesses that own underlying assets, which offset losses in long Live Cattle positions.

Most long positions are taken by speculators, which are non-commercial entities. In the massive selloff prompted by COVID-19, hedgers held their positions while speculators with long positions liquidated their positions in order to limit their losses. That exacerbated the selloff, but also thinned the market as open interest declined significantly. Typically, price volatility increases as markets thin.

Putting all of this together, packers know there is enough inventory to run their plants, so they don’t have to be as aggressive in the spot cash market. This is classic supply and demand resulting from fewer packing plants and more cattle. As a result, one would expect packer margins to increase.

At the same time, the smaller number of feedlots negotiating cattle prices makes the market thinner, giving packers more pricing power when there are a lot of cattle on feed.

In a panic selloff like we’ve seen twice in the last six months—following last summer’s packing plant fire and now COVID-19—hedgers inadvertently helped packers push cash fed cattle prices lower. Here’s how: As the speculative longs sell and the futures drop, feedlots make money on their hedged cattle.

Packers then have the ability to reduce their cash bids. As long contract holders, they reduce their bid at a smaller amount than the futures prices decline. Packers are in this position because hedgers have a greater incentive to sell when the basis widens in their favor.

Profits on their hedge positions exceed the money they give up by accepting the lower cash bid, so they agree to the lower price. Once hedged feedlots sell, the price they accept becomes the negotiated cash price and formula feedlots are forced to deliver at that price.

Crosby is a Wyoming rancher and principal with Custom Ag Solutions. The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of beefmagazine.com or Farm Progress.

You May Also Like