Bloat on fall pastures doesn’t have to be a problem.

September 16, 2015

If you’ve ever run cattle on legume pastures in the fall, you know how much of a problem bloat can be. Beyond just a problem, however, bloat can sometimes be a serious emergency.

“Fall weather with cool nights and moderate daytime temperatures make a perfect combination for bloat, because these are the optimum conditions for growth of lush forage,” says Carl Dahlen, Extension beef specialist at North Dakota State University. “The plants are not growing fast, and the cool temperatures keep them in a more vegetative state: slower to mature and become fibrous,” he says.

And forage that is low in fiber and high in protein is a combination that can cause excessive gas in the rumen. Take alfalfa, for instance. Emily Glunk, Extension forage specialist at Montana State University, says the higher the percentage of certain legumes in a pasture, such as alfalfa, the more risk for bloat. Cattle grazing pastures that are 100% alfalfa have increased risk because of the increased ingestion and digestion of soluble protein.

The more readily available the soluble protein, the greater the chance that it will lead to a buildup of stable foam in the rumen that causes bloat, Glunk says. This can be further enhanced if cattle graze high-protein legumes after a frost. “The cell walls within the leaves can become damaged; ice crystals puncture the cells, and this causes the soluble proteins to leak out and become more available, more quickly, within the rumen,” she says,

Then the fermentation process that goes on in the rumen takes over. “Gas is produced by normal digestion and fermentation. Cattle are constantly producing gas. As long as the animals can belch and this process is not obstructed, they do fine,” says Glunk. Sometimes you’ll see a full animal standing with its front end uphill, to facilitate easier belching.

18 photos show ranchers hard at work on the farm

Readers have submitted photos of hard-working ranchers caring for their livestock and being stewards of the land. See reader favorite photos here.

But when something causes the rumen to supercharge the fermentation process, like high levels of soluble protein, bloat can become a problem. “Bloat is accentuated by small particles and availability of rapidly fermenting material,” explains Dahlen. Frost has already started the breakdown process, and the foam created by the fermentation process rises above the top of the rumen contents and obstructs the valve between the rumen and esophagus, hindering the cow’s ability to belch.

Wheat pastures can be risky after a frost as well, for the same reason; the protein in the forage is more available. “Usually, bloating would occur on cereal grains that are bred to have higher-quality protein; there is higher protein availability to start with,” Glunk says. And legumes tend to have high-quality protein compared with grasses.

What’s more, anything that interrupts normal feeding activity, such as stormy weather, fly attacks, etc., can be a problem, because cattle may stop eating for a while. Then, if they’re on legume pastures when they go back to grazing and are more hungry than usual, they’ll load up on the lush feed, according to Dahlen.

Bloat is more likely when cattle are grazing in early morning — that’s when cattle are hungriest, because they haven’t been eating during the night. What’s more, dew increases the risk of bloat because it makes the feed more lush and cattle can eat it faster, with less saliva entering the rumen on a per-unit-of-feed basis. Saliva contains compounds that reduce the tendency for froth to develop in the rumen; with dew on the forage, cattle don’t have to mix as much saliva with the wet feed for chewing and swallowing.

Reduce the risk

“When grazing alfalfa in the fall, or even some cereal grains like winter wheat, I recommend pulling cattle off that pasture after a light frost and waiting a few days before putting them back in,” says Glunk. This allows time for the plants to decrease the amount of soluble proteins.

“If it was a killing frost, after which alfalfa will go dormant, it is best to wait at least five to seven days. By that time, the plant has gone dormant, and this length of time allows it to dry out and be more like hay, and not as risky,” she says.

“Make sure cattle are not hungry when first turned out on at-risk pastures. Feeding the animals before going out on the pasture helps slow down their eating, and they don’t load up so much,” she adds.

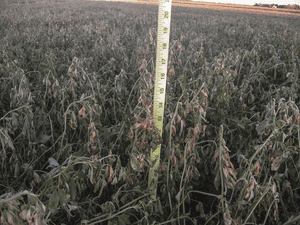

Frost-wilted alfalfa is high in available soluble proteins, which are a major factor in fall bloat.

“This also delays turnout until after the dew is gone,” says Dahlen. “Some people are swath grazing — cutting the alfalfa before letting the cattle into that portion of the pasture, so it has wilted for at least 48 hours. Then it’s not so lush.”

In addition to alfalfa, clover and other legumes may also cause bloat. “If the pasture is less than 50% alfalfa or clover, there’s a significant decrease in likelihood of bloat; the other non-bloating forages decrease the total amount of ingested soluble protein. They also contain anti-bloat compounds such as condensed tannins, and this decreases foam buildup,” Glunk says.

However, she says to always monitor cattle, just in case. “A mixture of plants does help, but cattle may find an area where there’s a higher percentage of legumes, and less grass,” she says.

“If the plants are uniformly dispersed, we can use intensive rotational grazing, so the cattle don’t have the opportunity to be as selective,” says Dahlen. “But if you have big pastures with regrowth and no way to break them up into an intensive rotational system, bloat potential might be higher,” he explains.

Safer legumes

To be safer, there are some non-bloating legumes that can be incorporated into pastures, such as sainfoin, birdsfoot trefoil and other high-quality legumes. “The non-bloating legumes contain condensed tannins, which usually decreases risk for bloat,” says Glunk. “The tannins bind to the proteins, making them less available.”

There are also some varieties of alfalfa that are safer to graze. “These ‘grazing alfalfa’ types are termed ‘non-bloating’ because they have lower amounts of soluble proteins. This decreases the risk, but it’s not a 100% guarantee,” she says.

Wait a few days before grazing legumes that have been burned back by frost.

Another thing a person can do is let clover or alfalfa get more mature before grazing. “There will be more dilution of soluble proteins due to an increase in the fiber component of those forages, decreasing digestibility. An alfalfa pasture at 100% bloom has less likelihood of causing bloat than a pasture where only 10% to 15% of the plants are blooming. The more mature plants are less lush.”

If you're thinking of swath-grazing a legume pasture, consider using electric fence to allow access to small strips at a time. “The benefits to swath grazing versus stockpiling is that you can cut the forage at the stage of maturity you want; the plants won’t become overly mature and stemmy. If it’s been cut and dried out [waiting seven or more days before grazing], a lush pasture will be safer to graze,” says Glunk.

“You will lose some quality with swath grazing due to leaf loss, and have to worry about precipitation [and mold] or ice sheeting that makes it unavailable to the animals. But it is generally an economical way to let the cattle harvest their own fall and winter feed. All you have to do is cut it, and the cattle are doing the rest. This makes a good compromise,” she says.

Leaf loss and drying decrease the quality somewhat. “But if you are weighing the benefits of maximum quality against the possibility of losing animals to bloat [especially with the value of cattle today], you might opt for the loss in forage quality,” she adds.

How to treat bloat

“If you start seeing a few animals with their left sides distended, calmly and slowly move them off that pasture,” Glunk says. Hurrying is counterproductive; if the animal is trotting or galloping, the rumen is jostled and more foam will obstruct the outlet for belching — with more risk for fatal bloat.

If the animal is not in imminent danger, the first option is to use a stomach tube to let out gas and put in something to break up froth. “This is the least invasive treatment. We need to quickly assess the situation and see what level we’re dealing with,” says Dahlen.

“If you’ve had this conversation ahead of time with your veterinarian, you can have a plan rather than being in a panic. If there is one thing that I know I need to do, the treatment plan becomes simple — and I don’t waste precious time. If I have five options for things that I could do, I might wait too long trying to decide, and the cow dies,” he says.

“If a stomach tube is not available, a garden hose works. Cut the metal end off because you don’t want to put metal objects into her rumen,” he says. If you are putting it down her throat, use something to keep her jaws apart so she doesn’t chew your hose in two. There are mouth speculums that you can thread the stomach tube or garden hose through, so she is chewing on solid material rather than the hose itself.

“A standard caution when putting the tube down — make sure the cow swallows it. Get it to the back of the mouth, and this will naturally stimulate a swallowing action. The animal must swallow it, or it will go into her windpipe instead,” Dahlen says. This is the same principle as inserting a nasogastric tube into the nostril, to the back of the throat, where it must be swallowed.

“There is always the danger, just like when tubing calves, of getting it into the wrong place. This is why we work with the animal. You can’t just jam and push it, or it might end up in the windpipe instead of the esophagus,” he says. Your veterinarian can walk you through some of this ahead of time so you have more confidence in what you have to do. No one wants to make a fatal error.

Once the tube is in place, allow any gas to come out, if there is a gas pocket and not just froth. “Then pour in a gallon of mineral oil or one of the other products available to reduce foam in the rumen. After you treat the cow and the rumen is no longer distended, continually monitor her and see how she is responding, and if she has any recurrences,” he says.

If an animal is in serious trouble, the only thing you can do is “stick” a hole in the rumen using an instrument called a trocar. “These are things you should discuss with your veterinarian,” says Dahlen. The distended rumen will be bulging upward on the animal’s left side. In a severe case, the right side may be distended, too, so if you have to use a trocar, make sure it’s on the left side.

“If the cow is down and gasping, get a trocar pushed through her distended left side, into the rumen, to let off the pressure. If you don’t have a trocar, a sharp pocketknife will work. It will make a larger opening, but your veterinarian can come later to clean that wound and stitch it up — and probably administer antibiotic to avoid peritonitis.” If it’s a question between cutting into her rumen or letting her die, most people will open the cow up and take their chances.

“I’ve used some of the little plastic screw-in trocars and these are handy, especially for calves [a cow’s hide is thicker, and they don’t work as well]. A person can thread it right in, and once it gets to a certain point, it just locks in. We’ve used these in chronic bloating cases, because you can leave it in there,” says Dahlen.

“You can pour the oil or anti-foaming agent in through the cannula after using a trocar. If it’s frothy bloat, foam may plug your stomach tube or trocar cannula. You need to make sure gas is still coming through. You may have to blow on the tube to clear it. With a trocar, the cannula stays in there, and you can just push the trocar back through it to remove the blockage,” he explains.

Heather Smith Thomas is a rancher and freelance writer based in Salmon, Idaho.

You might also like:

70 photos honor the hardworking cowboys on the ranch

Chipotle facing lawsuit for GMO-free claims

Will beef demand keep up with cowherd expansion?

Why you shouldn't feed your cows like steers in a feedlot

What's the best time to castrate calves? Vets agree the earlier the better

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)