Don’t shoot profit in foot — or anywhere else

Lead shot is still showing up in hides and skin at packing plants.

November 6, 2018

That statement is as obvious as it is ridiculous. But it’s an ongoing problem. Do some ranchers still think a load of lead shot is the best way to gather reticent cattle?

Well, yes. Some beef packers consistently find lead shot in hides and even beneath the skin of cattle being processed. Some say it’s due to hunters with a bad aim. Maybe so, but most is likely from frustrated cattle handlers.

“They can blame it on hunters if they want — but most is from gathering wild or sour cattle with a shotgun,” says a perturbed Ron Gill, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension beef cattle specialist.

“Packers have indicated there’s actually an increase in carcasses being detected with lead shot or bird shot. We cover it in BQA training every time — but it still happens. This is a quality assurance issue where there is a zero-tolerance threshold.”

Consumers love their burgers and other beef cuts. But with the minuscule chance that a burger is laced with lead shot or other contaminated material, moods change quickly.

Catching the problem

Thanks to sophisticated equipment used by safety-conscious packers, there’s little chance in that happening. But that doesn’t mean at least one or more cattle harvested every day doesn’t show up with lead shot or bird shot in their hides or even their skin, says Trevor Caviness, president of Caviness Beef Packers in Hereford, Texas.

Of the approximately 1,800 cattle harvested daily by Caviness, at least one will carry buckshot or bird shot when examined by initial carcass inspection. If one carcass slips through the keen-eyed packer personnel, that shot-contaminated beef is later identified by further high-tech testing on the line.

In either case, processing must be halted and the contaminated carcass removed. That means lost time, lost product and lost money. But the beef did not reach the consumer.

“They’re finding bird shot and lead shot in every cow plant, so it’s not surprising they are finding them at Caviness,” Gill says. “A lot of it is cranky bulls. They shoot to try and scare them. But most are cutter cows.

“It’s aggravating because the incidence rates are going up. It could be from inexperience in handling cattle. Also, some use rat shot or bird shot from helicopters to gather cattle. They say it doesn’t go through the skin. But it’s in the hide,” Gill says.

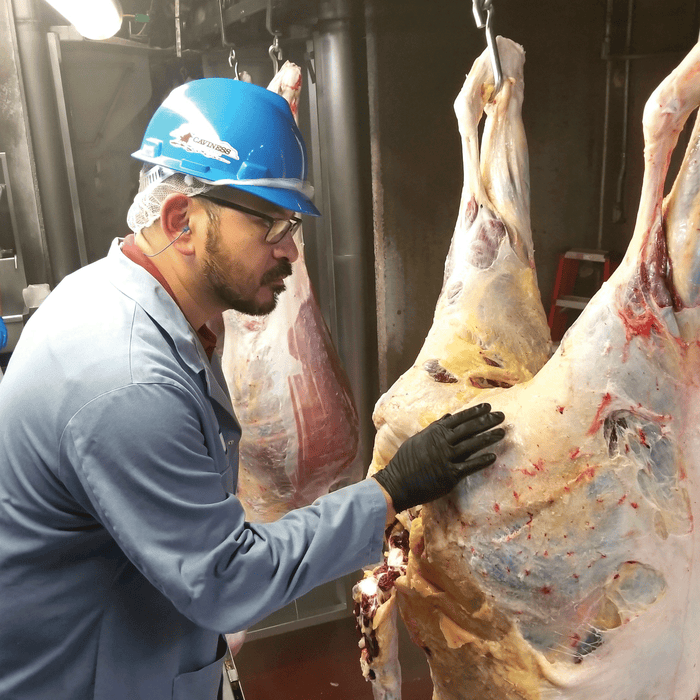

Jorge Aleman, director of food safety quality assurance at Caviness Beef Packers, shows the effects of bird shot that penetrated a hide. Aleman says of the 1,800 head the plant processes daily, there’s usually one with lead shot in the hide or skin.

“If a pellet shows up in grinding, they may have to discard 5,000 pounds of beef. Cow plants need to start taking more steps to discourage this practice by seeking restitution from sellers of cattle with shot in them — but they need product, and try to find all the cattle they can.”Caviness is primarily a cow and bull processing plant. About 90% of its cattle are cull cows and bulls, with more of the contaminated carcasses found after calves are weaned. Many come from smaller producers in neighboring states.

While some packers may be seeing more such cattle, Jorge Aleman, director of food safety quality assurance at Caviness, says the number of carcasses containing lead shot has declined slightly in the past few years.

“Our year-to-date data [through most of September] shows an average of one carcass per day, or one in about 1,800 cattle we harvest,” Aleman says. “That number is down from recent years. In 2016, the average number of carcasses containing bird shot or lead shot was 1.6 per day. That number dropped to 1.2 in 2017.”

Trevor Caviness welcomes those better numbers and believes producers are adhering to better animal welfare practices. “It sounds likes animal welfare initiatives are registering, and hopefully educating, folks,” he says. “But there is still zero tolerance. One incident is too many.”

Caviness has tracked the origin of shot-laden cattle, whether they’re from a sale barn or straight from a ranch. “We’ve done extensive tracking and found that it’s not specific from one region or another,” he says.

“Percentage-wise, there are just as many from Kansas as there are from East Texas, or western Oklahoma and eastern Oklahoma, or North Texas and South Texas. We thought it would be higher from more wooded areas, but it’s not.”

Detailed inspection

Aleman says carcasses containing lead shot, bird shot or other foreign material are normally identified when they are hanging on the line. “We use specific tags to separate them prior to fabrication,” he says. “We split those carcasses into smaller pieces and debone them to better identify buckshot levels.”

Once carcasses are deboned, they pass through one of three X-ray machines to identify foreign matter. Caviness says it’s key to prevent meat containing any foreign material from getting into the food chain.

Much of the plant’s product is for ground beef, either through grinding at its Amarillo, Texas, plant or by grocery chains or other food service customers. “We can’t let foreign matter reach consumers,” Caviness says. “We have a standard operating procedure for handling shot. We take extra precautions to locate shot, an injection-site needle or piece of a broken knife that may be buried in the muscle.”

Beef Quality Assurance guidelines

More producers are going through BQA training. There are specific BQA suggestions concerning lead shot and bird shot as part of its guidelines to deal with foreign matter.

The BQA handbook states: “Never use firearms to gather cattle. Develop alternative methods to control and capture animals. Work with hunters to prevent shooting cattle with any weapon. Educate hunters to the potential safety concerns associated with adulterated carcasses. Remove cattle from hunting areas when possible to avoid accidental shootings.”

Aleman says there are seven core criteria that packers must follow regarding the humane handling of cattle. Adds Caviness, “We hold ourselves to those criteria for handling incoming animals and train our employees on them. Producers should also use humane handling practices.”

He says the industry must self-police itself against cattle being moved with firearms. “We don’t want to face a situation like we have with antibiotic residue withdrawal violations,” he says.

For example, if product from a packer is found to contain residue, the packer is required by the USDA’s Food Safety Inspection Service to trace back the origin of the animal. That can be directly to a producer or a sale barn.

“If a producer receives two residue violations, their name, address and farm go on a public list,” Caviness says. “When that happens, we cannot accept cattle from them for 12 months. The producer must provide proof in writing that they have fixed the problem before their cattle can be harvested by a packer.”

He says it gets down to treating animals correctly. “In the name of humane animal welfare, the practice of shooting cattle to move them must be stopped. We try to eliminate the use of ‘hotshots’ or any other thing that inflicts pain on animals.

“So it’s obvious that cattle handlers shouldn’t use firearms to move cattle.”

Stalcup is a freelance writer based in Amarillo, Texas.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)