Cattle Market Outlook

thumbnail

Cattle Market Outlook

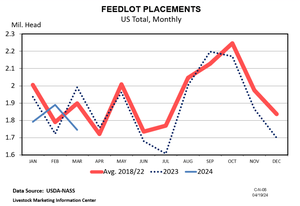

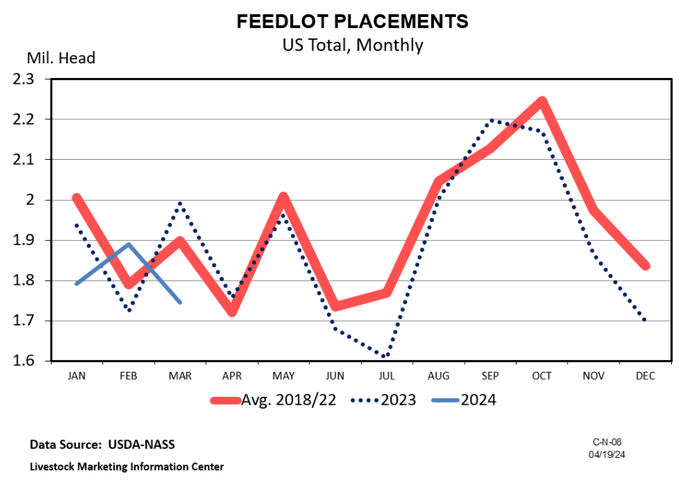

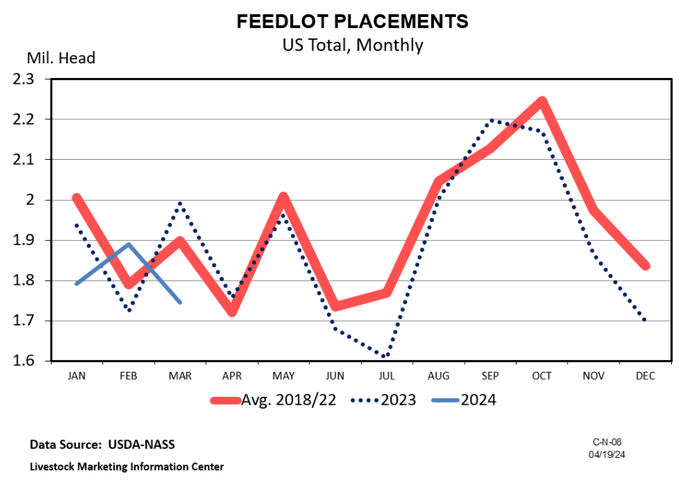

A bullish April cattle on feed reportA bullish April cattle on feed report

The April Cattle on Feed report highlighted a notable decrease in March placements compared to the same period in 2023.

Subscribe to Our Newsletters

BEEF Magazine is the source for beef production, management and market news.