If the D3 and D4 drought areas don’t get some life-saving moisture, the risk of more drought-forced liquidation will increase radically. What that means for the fall run and the cattle market going into 2019 is up for debate.

This is beginning to be far too much of a news story. But then again, the definition of “news” is something unusual or out of the ordinary. And the frequency and intensity of drought, particularly in the Southern Plains, has become so common that it may not qualify as news any longer.

But then again, anything that impacts the cattle market is most certainly news. And without a doubt, the return of severe drought to cattle country has and most likely will continue to impact cattle prices.

LISTEN: Drought pushes more cattle to auction barns

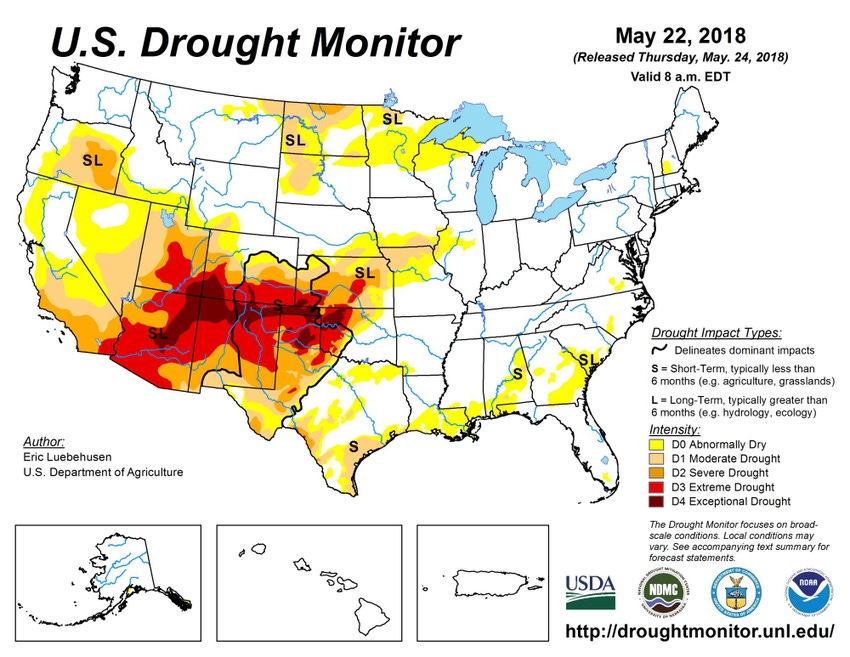

According to Rabobank’s second quarter global beef report, weather continues to be the single most disruptive influence in the U.S. beef complex. Extreme and exceptional drought conditions, starting last summer across the major winter wheat grazing regions, forced early placements of calves into grow yards and feedyards, according to the report. What’s more, as last week’s U.S. Drought Monitor shows, things aren’t getting any better

“The forced placements have substantially increased cattle on feed numbers, as well as creating the risk of bunched marketings of fed cattle this summer,” according to the report.

There are a lot of tentacles to all this, far too many to swing a sword at in a short blog. Let’s look first at cattle on feed.

Last Friday’s Cattle on Feed report shook the market with its estimate of 11.5 million head on feed as of May 1. The estimate is 5% above last year and is the second highest May 1 inventory since the series began in 1996. Clearly, drought-forced liquidation is one of the factors in that high on-feed number.

The COF report also indicates that net placements during April were 1.63 million, 8% below 2017. Here’s the breakdown by weight: Less than 600 pounds, 320,000 head; 600-699 pounds, 230,000; 700-799 pounds, 415,000; 800-899 pounds, 445,000; 900-999 pounds, 205,000; and 1,000 pounds and greater, 80,000.

Given the number of cattle already on feed combined with the number of heavyweight feeder cattle placed in April gives genuine concern about how we’ll navigate the summer doldrums once it hits. However, in my many years of association with cattle feeding, I’ve seen any number of situations where the bears were worried about a wall of cattle hitting all at once and crashing the market. Never, as best I can recall, have those predictions come fully to fruition.

READ: Fire and Ice: Surviving the effects of a natural disaster

I’m not an economist nor am I a very accomplished market analyst, but based on history, I suspect we’ll work our way through this situation as well. That doesn’t mean we won’t see fed cattle prices go lower, but I don’t anticipate a crash.

That’s because both domestic and international beef demand is remarkable and fed cattle harvest, as well as total federally-inspected harvest, has been strong as a result. At some point, U.S. demand will taper off as summer heat quashes grilling demand, but to what extent remains to be seen. I may be overly optimistic, but I suspect we won’t see domestic demand taper off as much as has been historically the case. Let’s hope.

But then there’s the drought. That shouldn’t have a big direct effect on the fed cattle market, but there may not be a lot of feeder cattle left out there to go on feed in the coming months. According to Rabobank, the early forced placement of calves has reduced available supplies of cattle outside feedyards, which should be price-supportive for summer and the second half of the year.

That be the case, cost of gains will go up if cattle feeders have to pony up for feeder cattle while looking at the possibility of fed cattle prices in the doldrums. What’s more, if drought affects corn production enough to make a dent come harvest time, it could affect cost of gains as well.

The Drought Monitor map shows 25 states reporting some degree of drought. Some are minimal and others are heart-breaking. According to Rabobank, the Southwest states showing the worst of the drought contain 34% of the beef cows in the U.S. and the total number of states showing some drought contain around 70% of the U.S. cowherd.

If the D3 and D4 drought areas don’t get some life-saving moisture, the risk of more drought-forced liquidation will increase radically. What that means for the fall run and the cattle market going into 2019 is up for debate. Let the discussion begin.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like