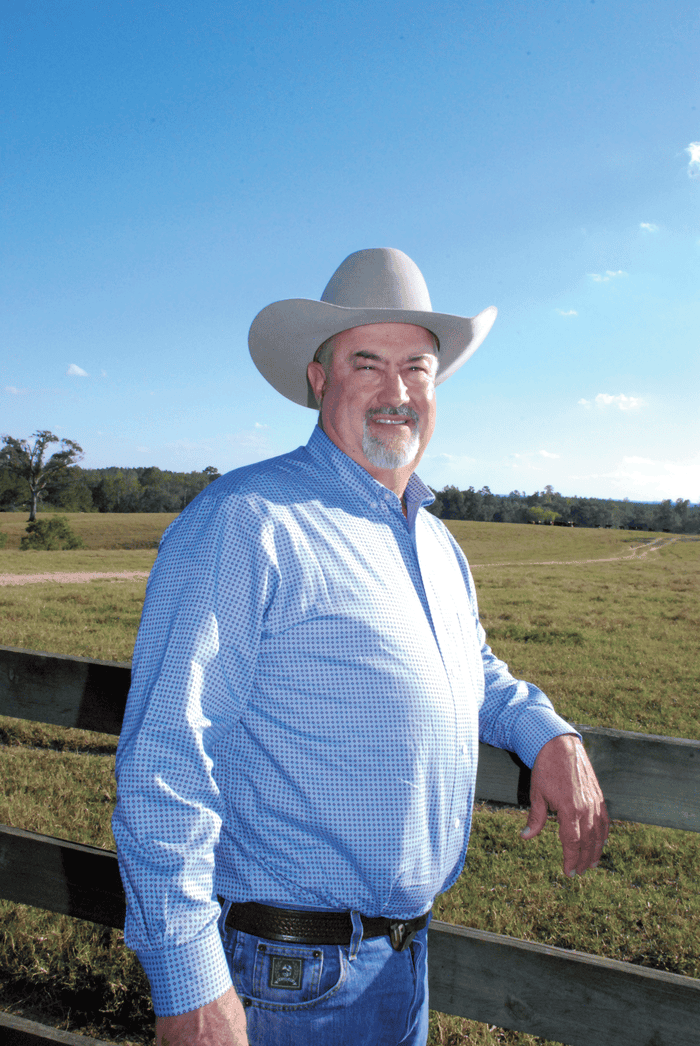

2018 Stocker Award Winner: Ted Parker

Buy a margin, get them healthy and put cheap gain on them. That’s Ted Parker’s formula for profit.

November 26, 2018

“You turn your money faster and you’ve got some cash flow,” says Ted Parker, explaining why he believes the stocker sector continues to offer opportunity to those looking for a start in the cattle business.

That’s how Parker — this year’s National Beef Stocker Award winner — got his start, borrowing money to buy 20 yearlings when he was 18 and then eventually buying his own place 10 years later. The National Stocker Award is sponsored by BEEF and Zoetis.

Ted Parker joins a long list of successful stocker operations as the 2018 winner of the National Stocker Award.

It helps to understand, except for an uncle, that no one in Ted’s family had been in the cattle business until his generation came along.

His dad was a postmaster and his mom a schoolteacher. They raised their kids at rural Sumrall, Miss. The Parker siblings — four boys and a girl — still own the house and 4 acres where they grew up.

Ted’s Grandmother Rogers used to joke that a genetic flaw must explain why so many of her grandkids took to cattle. Turns out that Ted and his wife, Janet, passed the family weakness on to their boys, Gent and Carl.

Buy the longest opportunity

Today, the homeplace of Ted Parker Cattle LLC, near Seminary, Miss. — about 20 minutes north of Hattiesburg — serves as the fulcrum for an expansive stocker operation that includes straightening out calves in Mississippi, growing some there on ryegrass in the fall, and others on wheat pasture — mostly in Texas and Oklahoma, as well as summer grass in Mississippi, New Mexico and other states, depending on the year.

“We’re trying to sell a 700-pound heifer and an 800-pound steer,” Parker says. In October, though, he was selling cattle a little lighter because he needed the room, and he could sell feeder cattle in the $150s and replace them with calves in the $140s, a swap as positive as it is infrequent. Other times, depending on the market, he may slow the turn of cattle and market them heavier.

He starts with calves assembled from Mississippi, Florida, Georgia and Alabama — calves as light as possible.

“If you buy a calf small enough, at some point, he will make you money,” Parker believes. “You may have to own him until he dies, but at some point, he’ll make you money.”

Parker retains ownership in some of his cattle, alone or in partnership, feeding them in Texas and Nebraska. “Feed the plain ones and sell the good ones” is his philosophy.

Between the stockyards and his buying stations (more later), Parker buys cattle year-round, except for one to two weeks when the holidays slow traffic.

A majority of calves are what most would consider high-risk: bawling, light, commingled from stockyards (sale barns).

Starting four years ago, though, he established a bonded buying station, Parker Livestock, at his homeplace in Covington County, trying to improve on calf health.

Parker Livestock doesn’t buy cows, but makes a market for everything else.

Customers bring calves — from singles up to 40 head or so — agree on a price, unload and walk out of the office with a check in about 10 minutes. They appreciate the immediate payment without sales commission — and for many, the chance to save shrink.

Improving calf health at the start

“The reason we got into the buying stations was to make cattle health better, and it has worked,” Parker says.

In fact, the difference in morbidity and death loss between what they call their drive-up cattle and those from various stockyards was significant enough that Parker established another buying station this year, about an hour away, in Pearl River County.

If calves come from a sale barn, they receive metaphylaxis and are vaccinated with a 5-way and blackleg. The protocol is the same for cattle acquired through their buying stations, except for the metaphylaxis.

Parker preconditions flyweight cattle at the homeplace. Buying-station cattle weighing 450 to 650 pounds go to another location in Pearl River County.

Typically, if calves arrive late in the day, they’re processed the next morning. If they arrive early enough in the day, they’re processed in the afternoon.

Buying-station cattle remain separated from stockyard cattle for the first 40 to 50 days. Usually, within a day or so, the calves move to grass pastures of 40 to 50 acres.

Stockers that flow into and out of Ted Parker’s operation are a mixed bunch. But it’s the bottom line, not the hide color, that matters. He starts with calves assembled from Mississippi, Florida, Georgia and Alabama — calves as light as possible. “If you buy a calf small enough, at some point, he will make you money,” Parker says. “You may have to own him until he dies, but at some point, he’ll make you money.”

“We don’t worry about sexing them at that stage, but we try to keep the sizes similar,” Parker explains.

During the preconditioning period, cattle receive free-choice feed — a commodity total mixed ration — with mineral and an ionophore. Ration ingredients used over time include wet corn gluten, corn and cottonseed hulls.

After 40 to 50 days of preconditioning on grass and the commodity ration, Parker and his crew sort the calves for size and sex — and in some cases, quality. Keep in mind, most of his steers were bulls when purchased.

For perspective on how all of this blends together after the preconditioning phase this fall, here’s a breakdown: 3-weight steers were destined for Parker’s own ryegrass, 3-weight and 4-weight heifers were being placed for gain on ryegrass, 5-weight cattle were heading to wheat pasture, while 4-weight steers and those weighing more than 500 pounds had a date at their grow yard.

Low-cost gain, multiple options

“Our No. 1 goal is to make the cattle healthy, and then put cheap gain on them,” Parker says. That’s after buying cattle with a price that provides margin.

If you’re talking Mississippi and some other parts of the Southeast, the conversation about low-cost gain starts with ryegrass and the unique advantages in this part of the world. There are plenty of calves from handfuls of cows that are a byproduct of timberland ownership.

Chicken houses dot the landscape, making inexpensive fertilizer in the form of chicken litter. Daily gains on ryegrass here can be around 3 pounds.

In the fall, Parker overseeds pastures with ryegrass, which usually will be ready by February. “We won’t take the cattle off when we overseed,” he explains. “The cattle are ‘walking in’ the seed.”

Tilled ground is planted to ryegrass from September to the middle of October. Those pastures usually are ready for turnout by Thanksgiving.

Relatively close proximity to the Port of New Orleans means that Parker often can find feed bargains, such as the milled rice he’s holding. Discounts can be had with volume — Parker Cattle LLC is large enough to purchase barge loads — and the opportunity to buy salvage-quality feedstuffs. Byproducts are blended into a total mixed ration Parker uses in preconditioning pens.

Incidentally, Parker doesn’t wave the flag for any particular ryegrass, but he makes sure to sow one of three different hybrid varieties on each pasture or field he manages. His reasoning is that depending on the year, one variety will outperform the other. This way, he knows production will usually be superior on at least some of his pastures.

Besides his own land, as with wheat pastures out West, Parker calves also graze other people’s ryegrass on a gain basis. That’s how he started: leasing ground.

“You couldn’t own enough land to do what I wanted to do,” he explains.

What he wanted was to own cattle and grow the operation large enough to provide a living for his family. “Breaking even has never been an option for me,” he explains.

A few years ago, Parker added another dimension to low-cost gain via what he calls their “grow yard.” It used to be a dairy with 1,800 cows under roof. Now, it houses calves receiving a silage-based growing ration.

“There’s a lot of feed that comes down that Mississippi River, and usually there’s a bargain to be had,” Parker says. The Port of New Orleans is about three hours to the south.

“We’re big enough that we can buy a barge load,” Parker explains. The sheer volume offers discounted prices, as does the fact that there are bargains to be had because of quality.

Maybe it was corn gluten feed that got too hot and caught fire along the way. Might be milled rice waterlogged after a barge was loaded incorrectly. It could be any of the reasons grains destined for overseas markets end up not making the grade.

Spreading the risk

By the time Parker markets cattle, given the multiple sorts starting the day cattle are received, loads of cattle look as uniform as if they came from the same cow herd.

May, when cattle come off ryegrass, and September, when cattle come off summer grass, are usually Parker’s heaviest months for shipping cattle. As with his buying, though, he sells something every week.

“With the volatility in the market, I always thought if you buy and sell all of the time, it’s a pretty good hedge,” he explains. “I was never scared about losing a lot of money, but I’d never put all of my eggs in one basket. I’ll hedge, feed, forward-contract — a little bit of everything.”

Parker got his first taste of trading commodities with pork bellies when he was 18. With skin in the game, he says, you learn fast. Two of his older brothers owned a commodity business at the time.

He gained more experience with the price risk management aspects of the board soon after high school, when he headed to Chicago to work as a runner on the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange; his younger brother did the same before him. Ultimately, Ted got a seat on the floor and traded for a year.

Learning is growing

Along the way, Ted and Janet served and continue to serve leadership roles in a variety of organizations, including the Mississippi Cattlemen’s Association, Mississippi Farm Bureau, Mississippi Beef Council and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

Moreover, Ted has been more than willing to help others get started in the stocker business, be it with information and experience or going to bat for them in striking a deal.

“I haven’t done anything special,” he says. “I never thought of it as competition — just thought of it as helping my friend.”

Those friends in the stocker business include family. Ted credits his older brother, Harold, with some of his initial stocker education when he was still in high school. Ted was working for the local veterinarian at the time and received a cow as a bonus.

Though you can find a number of Parkers and their kin running stocker cattle in Mississippi today, Parker explains they each run their own business. The same goes for his sons. Gent and Carl work for the family operation, but they also buy, manage and market their own cattle.

“My goal is for my boys to take this operation and run with it, but I think the best way they can do that is to own their own cattle and have problems with their own cattle,” Parker says. “You just learn more.”

For anyone starting out, Parker offers a couple of lessons learned from experience.

Ted Parker, winner of the 2018 National Stocker Award, stands on a pile of salvage-quality pelleted corn gluten feed that’s used in a growing ration. Parker won the National Stocker Award, sponsored by BEEF and Zoetis, for his ability to take high-risk, lightweight calves and turn them into high-value feeders.

“I think successful people love what they do,” he says. “Don’t worry about making money, worry about doing what you love, and it will take care of itself.”

After all of the years in the business, Parker says, “I love to see these calves come in for 45 days — and then, whether or not you have to doctor them, see them ready to go. I like watching them get healthy more than watching them grow.”

Next, Parker suggests, “Start small, and don’t grow too fast. You can get yourself into trouble by growing too fast.” He leased ground for a decade before buying his first acre.

Although breaking even over the long haul was never an option, Parker also understood up front that there would be economic losses along the way. “You have to keep enough back to stay for when it turns around again, because it will turn around,” he emphasizes.

Be patient

When he and Janet got married, she had a full-time job. Ted had a couple of different jobs, including some order buying. They basically lived off what Janet made and poured everything else back into their stocker business.

Ted and Janet Parker stand at the entrance to their Mississippi operation. In addition to their home base in Mississippi, Ted runs stocker cattle in a big handful of other states, as well as retaining ownership in feedyards in Texas and Nebraska. He is the winner of the 2018 National Stocker Award, sponsored by BEEF and Zoetis.

“We never took a dime out of it for 20 years,” Parker says.

Proud as he is of what’s been accomplished, he’s quick to share the credit.

For one thing, he explains, “I have some employees who have been with me a long time, close to 20 years — and they’re a big reason we’re at where we are today.”

Before that, though, Parker says, “God has blessed us, giving me the opportunity to live out my dream and own cattle.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)