thumbnail

Cattle Market Outlook

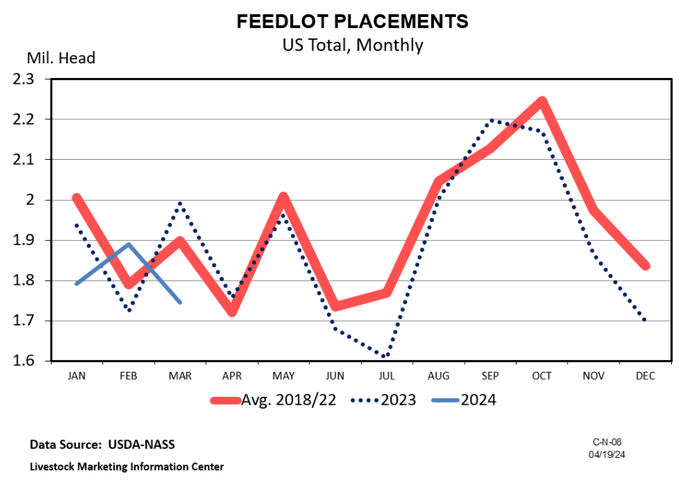

Does history repeat itself?Does history repeat itself?

In the cattle marketing business, it’s not about getting lucky and the history repeating. It’s about learning relationships and knowing when to buy and sell cattle.

Subscribe to Our Newsletters

BEEF Magazine is the source for beef production, management and market news.

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)