thumbnail

Market news

U.S. beef, cattle demand posts early 2024 highsU.S. beef, cattle demand posts early 2024 highs

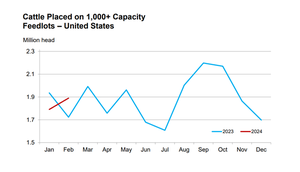

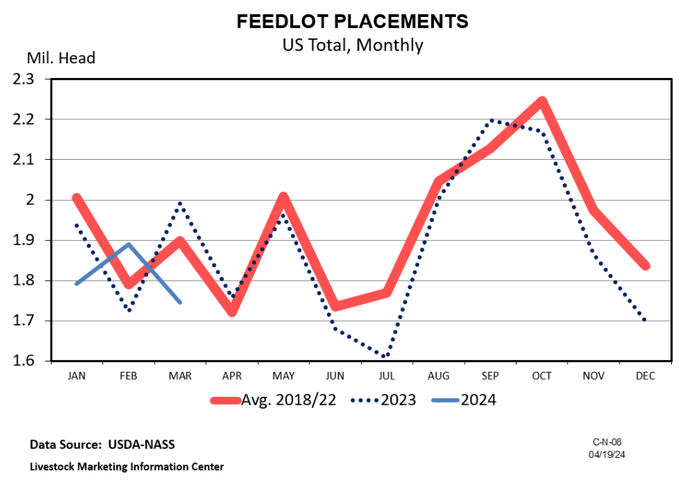

Trade deficit continues to widen as beef production declines.

byAnn Hess

Subscribe to Our Newsletters

BEEF Magazine is the source for beef production, management and market news.

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)