Liver Flukes Expand Range To 26 States

Once relegated to the more moist environments of the Gulf and Pacific coasts, liver flukes have extended their range to 26 states.

March 27, 2012

In the hierarchy of internal parasites in beef cattle, there’s little doubt that the nematodes (Ostertagia, Cooperia, etc.) are the headliners. But there’s an ambitious understudy – liver flukes – inching their way into the spotlight.

It wasn’t that long ago that flukes were essentially concentrated on the moist Gulf and Pacific coasts. Due to the modern movement patterns of cattle, wildlife and hay, however, flukes are now found in 26 states. In fact, a recent National Beef Quality Audit found that 24% of U.S. cattle had liver flukes at slaughter, resulting in liver condemnations that cost millions of dollars annually.

The U.S. can boast of three species of flukes. The cattle fluke (Fasciola hepatica) is the most widely distributed, according to James Hawkins, a Jackson, MS, DVM and consultant for Merial. Then there’s the deer fluke (Fascioloides magna), and the lancet fluke that exists in New York, Maine and Eastern Canada.

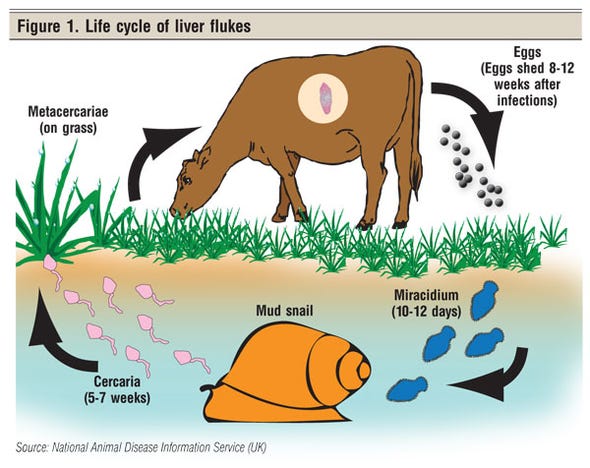

Flukes depend on a small snail for an intermediate host. Tom Craig, Texas A&M University veterinary pathobiologist, says cattle ingest these parasites as cysts attached to plants consumed in or near water. Tiny flukes are released from the cysts during digestion, which penetrate the gut wall and migrate to the liver, where they feed – and destroy tissue. They then migrate to bile ducts to grow into adults and lay eggs.

The eggs travel with the bile into the cow’s gastrointestinal (GI) tract and are passed in manure. Feces containing fluke eggs must land in water in order for the eggs to hatch into free-swimming miracidia, says Floron (Buddy) Faries, Jr., DVM, Texas AgriLife Extension. If the manure lands on dry ground, the eggs die.

The eggs will hatch in about 30 days if the water temperature is above 55°; and the tadpole-like miracidia immediately begin swimming in search of a snail host. Upon penetrating the snail, they spend two months propagating, after which they emerge again as swimmers to attach to a plant growing in water, to be eaten by a cow.

“Wherever there’s standing water, snails will be present when weather warms up in the spring. If flukes come out of the snail in July, however, the water may not be there, and this will break the life cycle,” he explains.

“If there’s three months of water – one for eggs to hatch, and two months to develop in the snail – flukes emerge and encyst on grass. After that, the water could dry up but the flukes will still be there, waiting on grass plants. Cattle might eat that grass, or it could be cut for hay, and flukes get into the cattle that way,” Faries says.

Swamps can be fenced off to keep cattle away from flukes, “but when feed is short in a drought, this may be the only green place on the farm,” Hawkins says. Thus, some producers end up with high levels of fluke infection during a drought because cattle are grazing wet areas they don’t normally graze.

All species of flukes can kill cattle, but deaths are rare. “Generally we see chronic, slowly developing disease that reduces weight gain or affects overall animal health. Cows become poor doers and eventually get culled,” Hawkins says.

Liver damage opens the way for clostridial bacteria that cause redwater disease. With liver damage, the immune system is also compromised, increasing susceptibility to disease and diminishing ability to respond to vaccine or antibiotics.

“Liver damage affects everything the body needs to do in converting nutrients into utilizable proteins, energy, vitamins, etc. Liver flukes affect gain in young cattle, but this is usually a slow-developing problem compared to the effect of worms,” Hawkins says.

“Any time an animal dies on your place, check the liver. If there is severe damage, you can see it, and you’ll know you have flukes,” he says.

Treatment

It takes two months for flukes to migrate into the cow’s liver and mature, at which time they are most susceptible to drugs. Thus, treatment for flukes must be administered five months after the eggs hatch from manure and end up in the cow, Faries says. If this life cycle is occurring from April through August, treat for cattle liver flukes in September. “If it was too cold in April or we didn’t have rain, it will be a little later,” he adds.

It takes two months for flukes to migrate into the cow’s liver and mature, at which time they are most susceptible to drugs. Thus, treatment for flukes must be administered five months after the eggs hatch from manure and end up in the cow, Faries says. If this life cycle is occurring from April through August, treat for cattle liver flukes in September. “If it was too cold in April or we didn’t have rain, it will be a little later,” he adds.

In some climates, if there’s sufficient water and warmth, there may be another cycle in the fall. “When treating cattle for both worms and flukes, it can be difficult to find the proper time, since in our climate (Texas), it’s usually best to treat for stomach worms in early summer after spring rains. People often use a dewormer that kills both, and feel they’ve accomplished their goal, but didn’t actually kill the flukes,” Faries says. If climate is mild or there are warm water springs in a pasture, flukes are possible any time of year.

Craig says late fall is generally the best time in the South to treat for flukes. “The drugs presently available in North America, used at prescribed dosage, only kill adult flukes in the liver. They’ve already done their damage – during migration through the liver. We don’t have an effective drug to kill them during that period,” Craig explains.

You need to know the life cycle of the flukes in your area, and how long it takes for immature stages to become adults. “This could be in late winter or spring in the Northwest where there are wet winters,” Hawkins says.

“Target the time of year when there’s the most transmission, and treat at least eight weeks later. This would be September-November in the Southeast, and March-May in the Northwest. You’d get less infection during the other months. Pay special attention to replacement heifers and young bulls to ensure they’re gaining and/or producing to their potential, as well as to save on feed costs” he says.

Amoung the products that kill liver flukes are Ivomec® Plus (Merial); Valbazen® (Pfizer) and Noromectin® PLUS (Norbrook).

“To get deer flukes, however, you must use 2-4 times the recommended dose for cattle flukes; even then, you don’t always get a good kill. Deer flukes are more resistant to the drugs. Cattle are an abnormal host, treating them as foreign and walling them off. After they become adults, they pair up in the liver and the cow walls them off with a fibrous connective-tissue capsule, like an abscess,” Hawkins says.

The cyst becomes a mass of expanding necrotic tissue. “Because of the fibrous capsule around them, drugs can’t touch them. Cattle are a dead-end host; after the flukes get walled off they can’t pass eggs (and we can’t check feces for eggs, for diagnosis). All we kill, when treating deer flukes, are the migrating immatures,” explains Hawkins.

“In our studies in Minnesota, we often found very little normal liver tissue left, in calves with deer flukes,” says Bert Stromberg, University of Minnesota professor of parasitology. “We recommend treating calves at the end of summer – into the fall – as deer flukes start maturing. It would be nice to have something that will kill immature stages more effectively, but we have to treat with what we have, and hope to knock numbers down. The only way to control deer flukes is to control deer, and that’s difficult or impossible.”

Worms vs. flukes – who’s the baddest on the block?

A recent study at Louisiana State University (LSU) sought to determine whether worms or flukes were the more important internal parasite in cattle, and what happens if cattle have both?

Conducted over a four-year period at LSU’s Alexandria experiment station, weaned heifers each year were divided into four groups of 24 head. One group was treated with injectable ivermectin – to kill worms but not flukes. Another was treated for liver flukes only, using Curatrem (containing clorsulon). The third group was treated for both worms and flukes with both products, and the fourth group served as untreated controls.

The heifers grazed ryegrass pasture in winter and were supplemented with corn-based concentrate to gain 1 lb./day in order to reach breeding weight. The pastures were known to have both worms and flukes.

Results showed gastrointestinal (GI) tract nematodes had the most profound impact on gain.

“Compared with the untreated control group – which actually did well, gaining 1 lb./day (53 lbs.) – the dewormed heifers averaged 23-25 lbs. more. They gained more than needed for breeding weight. That group could have been backed off a little on feed, which would have saved a lot of money,” Hawkins says.

The group that perennially did best received both worm and fluke control. They registered better weight gain, and increased conception rates, while the heifers treated for just flukes gained 23 lbs. more than the untreated controls, on average, Hawkins reports.

Moreover, the study found worms were more important than flukes for affecting weight gain, which is probably representative of most ranch situations, researchers say.

“But if a producer sees signs of heavy fluke infections, this could be different. I’ve seen several instances in which young cattle – replacements or stockers – died on pasture from liver failure,” Hawkins adds.

Heather Smith Thomas is a rancher and freelance writer based in Salmon, ID.

You May Also Like