The role of speculators in the futures markets

While speculators get the blame when futures markets become volatile, they play an important role in making the markets.

March 19, 2020

Futures markets inherently stoke emotion from observers and sometimes participants – especially in times of market turmoil both up and down. And generally, much of the noise revolves around speculators.

That’s sure been true in recent weeks. The sentiment goes something like this: “It’s the speculators and their respective selling pressure that is driving market to new lows.”

Pervasive criticism of futures markets and speculators is an enduring theme. For example, Charles Geist describes it this way in his great book titled, Wheels of Fortune: The History of Speculation from Scandal to Respectability:

Almost from the very beginning, the markets have been called every imaginable name, from gambling dens to vital centers of commerce. They have been decried as having no economic value…The commodities futures markets invite a wide panoply of interpretation – from being the home of Satan himself to the cathedrals of the messiahs of business, depending upon one’s point of view.

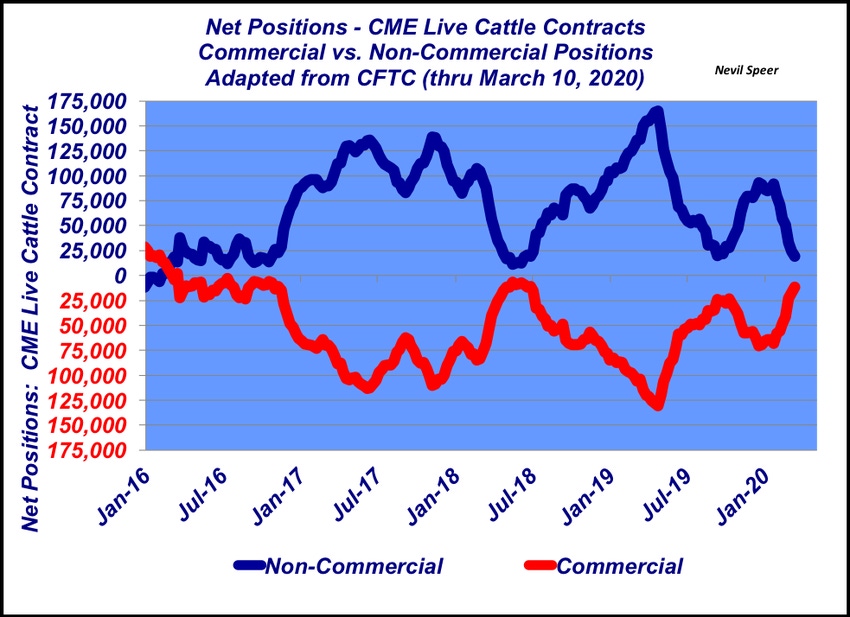

This week’s graph provides some perspective for those concerns. The illustration highlights weekly net positions among commercial (hedgers) and non-commercial (speculators) market participants, respectively. Most pertinent to recent market action, the net non-commercial position has declined from being net long around 90,000 contracts in January to just under 20,000 contracts on March 10. In other words, the speculators have liquidated roughly 70,000 contracts in recent months.

However, that didn’t occur in a vacuum. Simultaneously, the commercial net position has shifted from being net short nearly 70,000 contracts to 11,000 contracts during the same time frame – a difference of nearly 60,000 contracts. So, while the speculators have been selling to get out of their long positions, the commercial traders (hedgers) have facilitated that occurrence – they’ve acted as purchasers thereby enabling that liquidation (selling) to occur.

Interesting to note, during the height of the financial crisis and subsequent concerns about inflation due to fiscal stimulus, the concerns were on the opposite side of the equation. That is, there were loud detractors about speculators being long and causing prices to go too high; speculators were purchasing “too many” contracts.

Nevertheless, this week’s illustration represents classic futures market theory. The speculator takes a long futures position with expectation that price in the future will exceed current futures price, assuming rational decision-making. The hedger on the other side wants to avoid risk; he/she is buying insurance from, and transferring risk to, the speculator.

As such, the short ≈ must be willing to sell a futures contract at some level below the expected future price of the commodity. Otherwise the hedger cannot induce the speculator to assume a long position—the discount being what the hedger pays the speculator for assuming risk. And thus, the ebb and flow of net long vs. net short among the non-commercial versus commercial traders, respectively.

No doubt, the damage to price levels in recent weeks has been sharp and painful. However, within that context, it’s important to remember that futures markets operate on a system of perfect balance. That is, for every buyer there must be a seller—and vice-versa.

For example, if a speculator wants to sell a contract, that can only happen if there is someone on the other side willing to buy that contract at some given price. And in the case of the past several weeks, that’s seemingly been the commercial side of the market. Leave your thoughts in the comments section below.

Nevil Speer is based in Bowling Green, Ky. and serves as director of industry relations for Where Food Comes From (WFCF). The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of WFCF or its shareholders. He can be reached at [email protected]

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)