Genes: Hill-topper or bottom-dweller?

Research looks at genetic aspects of beef cattle “range-ability” and terrain use.

April 1, 2019

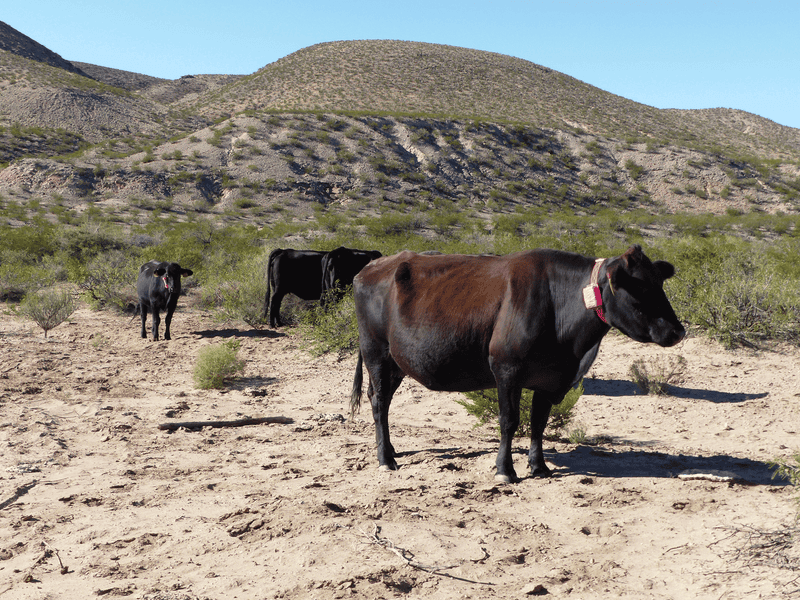

Ranchers who pasture cattle on rugged rangelands or desert country have known for a long time that some cattle do better out there — traveling farther, climbing higher, using more of the landscape — than others. Now, researchers are showing that there is a genetic component in “range-ability,” enabling some cattle to be more ambitious foragers.

Cattle can be trained to use higher country and not be “bottom-dwellers,” but there is also an innate tendency in some cattle that makes it easier for them to learn to use the steeper slopes and far corners of a pasture. If some cattle can do this willingly, it saves the labor of trying to teach them — or to keep them from spending so much time in riparian areas.

These studies are difficult to do; it’s hard to get data assessing the way cattle use rangelands. The willingness to travel farther and climb higher is difficult to measure, but GPS technology now enables researchers to track cattle and see where they go.

Cattle breeders have been selecting for traits like growth, bigger weaning weights and carcass traits that are much easier to measure than willingness to use rugged terrain. Few seedstock breeders select for cattle that cover the country — especially in the East, where grazing distribution isn’t as much of an issue.

“In the West, it’s a big deal,” says Derek Bailey, professor of grazing management and behavior in the Department of Animal and Range Science at New Mexico State University and one of several researchers working on projects tracking cattle use on rugged and extensive Western rangelands.

“Pastures are big and rough, often on public lands with certain regulations and standards. Permittees are not allowed to overgraze riparian areas, for instance; and if they do, stocking rate will be reduced or some other grazing management changes will be implemented. This can make it very costly for the ranchers using public lands.”

Permittees try to keep cattle out of the bottoms by herding or fencing off riparian areas. Otherwise, low areas and regions closest to water are often overgrazed, and higher areas or regions farthest from water aren’t grazed enough. Ungrazed grass simply creates more fuel for fires. On many ranges, about one-third of these big pastures go ungrazed.

Sometimes water can be developed in those distant, higher places, or cattle can be enticed with salt or protein supplement.

But it can be a chore to get salt and supplement into rugged areas with no roads. Often, fencing in this terrain is not an option.

All these things cost money, and if there were a way to select cattle for “ambitious use of terrain,” it would make ranchers’ jobs easier and use of range pastures less expensive. It’s hard to tell by looking at a cow, however, whether she’ll be a good range cow, and there are “lazy” and “ambitious” cows in every breed.

“Tall cows, wide cows and other things you can readily measure are unrelated to this, so it seems to be a separate trait. We see all kinds of cows on top of the mountain and all kinds in the bottoms,” Bailey says. Motivation has little to do with conformation.

Genetic research

“We know there is a genetic influence on grazing distribution. It is a heritable trait, and should respond to selection,” says Bailey. Some researchers are now looking at genetic markers and hope to eventually determine breeding values that could be used in selecting cattle.

“Because we are using tools where we can genotype either 50,000 or 800,000 genotypes per animal, we are seeing a lot of hits on chromosomes in regions that harbor genes involved in locomotion, feed efficiency, overall metabolism, etc. There are many things that just make a lot of sense,” says Milt Thomas, professor of beef cattle breeding and genetics at Colorado State University, one of the researchers looking into the genetics involved in this trait. Many of these things are interrelated.

“Another thing that pops up, since we’re looking at many cattle at high altitudes, is hypoxia [oxygen deficiency],” Thomas says. “There are several chromosomal regions jumping out at us as being important.”

A CSU graduate student, Courtney Pierce, has been working on her thesis in this project. Her work is showing that the range-ability trait is very polygenic (meaning multiple genes are involved).

“There is not just a single gene; it’s lots of genes — whole-animal physiology — many things that are driving a cow to be what we call a hill-topper versus a bottom-dweller,” explains Thomas.

Often, when people start a new area of research — particularly in genetics — they are looking for the “magic gene” or genetic marker. “It’s not going to be simple for this one. It will be what we call a quantitative, complex polygenic trait. This does, however, lend itself very well to our classic EPD system. EPDs are the most appropriate tool for selection of quantitative traits,” says Thomas.

Will producers one day be able to send in blood samples of bulls and rank them as to which would be best to sire hill-climbing daughters? Perhaps, Bailey says.

But there’s a catch. “This kind of trait selection will not be as accurate as selecting for growth, weight or any other things that can be more easily measured, however.”

What makes an ‘ambitious’ cow?

“Terrain use” is the term Bailey uses for the differences in cattle that are ambitious in contrast with bottom-dwellers. “Regardless of variances in vegetation in certain areas, a steep hill is a steep hill, no matter what; and a long distance from water is always a long distance,” Bailey says. “It takes more effort to climb, or to walk farther to water, but some cattle are willing to do it.”

Bailey developed two indexes to help with data evaluation — rough and rolling. The rough index incorporates slope and elevation. The rolling index includes slope and elevation along with distance from water.

The answer, “Because it’s there,” to the question, “Why did you climb that mountain?” may be adequate for an adventurous person — but what makes an adventurous cow do that? A multiranch, multistate research study aims to find out. Certainly, water, salt and minerals, along with other management factors, play a part. But the study digs deeper to see if genetic markers can be found, and ranchers can select for the hill-toppers.

“We can starve the ‘lazy’ cattle into leaving the bottoms and climbing higher, but this is detrimental to the cattle and the land,” he says. They eat out the bottoms before they climb higher.

“I was part of some research in Montana where we split a herd. The ones that previously liked to climb we kept separate from the cows that didn’t like to climb, and we watched them for three years in separate pastures.”

The cattle that climbed in the past continued to climb, and their pastures were not beat out in the bottom as much as the pastures of the nonclimbers. There was a measurable difference in grass height at the end of the season — 3 inches for nonclimbers and 5 inches for climbers.

The nonclimbers’ pasture failed the typical Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service standard for riparian area stubble height, and the climbers’ pasture passed, Bailey says. What’s more, the hill-toppers climbed higher even when there was still grass in the bottoms.

“We can’t see any difference in how they perform, though we know there is some energetic cost in climbing or traveling farther, so they must be getting more from the feed [or have more feed efficiency] to offset that effort,” says Bailey.

Bailey says several research projects are underway in Idaho and Arizona on residual feed intake and feed efficiency on pasture. The results indicate that the hill-toppers may be lower-intake, more feed-efficient cattle than bottom-dwellers.

“So we have a couple pieces of information suggesting that hill-climbers may be more efficient animals. Some of the candidate genes we found in our analysis that were associated with terrain use are also associated with feed efficiency,” Bailey says.

How are you going to get them from down here to up there? That question has been plaguing Western ranchers for decades. There are various ways — herding, salt and protein, water development — but some cows just seem to climb and forage better than others. Research may ultimately develop a DNA test to help select for the hill-toppers.

“Some of the candidate genes we’re looking at for terrain use are also related to things like heat stress and hypoxia. Cattle that are vulnerable to heat stress don’t do as well in summer and may spend less time grazing on a hot day. Cattle that can tolerate heat might climb better,” he says. They also may stay out grazing longer before they seek shade, lie down or stay farther away from water longer.

“If they are not as bothered by the heat, they may just keep walking and grazing longer, and end up higher on the mountain or farther from water. There are many things we still need to know, but genetically we’ve found some ways we might be able to select cattle for these desirable traits,” says Bailey.

Research protocols

“In our recent study, we had a student at Colorado State University tracking 330 cows, working with 17 ranches and different terrain. We recently pulled collars off cows from ranches in California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Wyoming,” Bailey says.

“We tracked some cattle all summer from branding [range turnout] to weaning, and some [in New Mexico] in winter from weaning until calving the next spring — samplings from all kinds of places, in all kinds of herds, large and small,” he says.

Analyzing all those data, however, takes time. “It’s still a bit slow; we are now analyzing data from more than 330 cows, but the GPS system takes a measurement [when cows are moving around] every 10 minutes,” says Thomas.

“If cows wear GPS collars for two months, there’s a lot of data to analyze. We have to look at maps and overlay that data on a topographical map to see where the cattle went,” he says.

Bailey says the study has been aided by additional researchers in Colorado, California and Arizona. “We also appreciate all the ranchers we work with. They have really helped us and have been a pleasure to work with,” Bailey says.

Smith Thomas is a rancher and freelance writer based in Salmon, Idaho.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)