Separating fact from fiction on farting cows

Are the mainstream media and anti-beef activists correct in their accusations that cattle are a major contributor to climate change? Here’s a look at the facts.

March 6, 2019

By Sara Place, Ph.D.

Which end of the cow is responsible for most of its methane? Let’s face it: anyone with a coin has a 50-50 chance of getting that right. But based on much of what I’ve read over the years, many mainstream journalists get it terribly wrong. No, it’s not cattle flatulence that is the source of most of the methane gas from cattle. It’s eructation – or burps.

Greenhouse gases from beef cattle production have come under increased scrutiny in the past few months. A seemingly endless series of reports and articles are driving a narrative that eating less meat is a key answer to climate change. Knowing the facts is important in this debate, which isn’t going away any time soon.

As the senior director for sustainability research at NCBA, a contractor for the Beef Checkoff, answering questions about greenhouse gases and cattle is part of my job. While I’m an animal scientist, not a climate scientist, I do have a unique and pertinent background in this field, conducting research where I measured methane emissions directly from cattle. It is true that cattle produce methane, a greenhouse gas 28 times more potent at trapping heat than carbon dioxide, but it’s unlikely methane from U.S. cattle has been a factor in increased global average temperatures in the past few decades.

This is the core message of a new fact sheet available from the beef checkoff’s sustainability research program. In the fact sheet, C. Alan Rotz, Ph.D., USDA-Agricultural Research Service, and Alexander Hristov, Ph.D., Pennsylvania State University, explain how methane from ruminant animals like cattle is a part of a natural carbon cycle that is different from methane from fossil sources like natural gas.

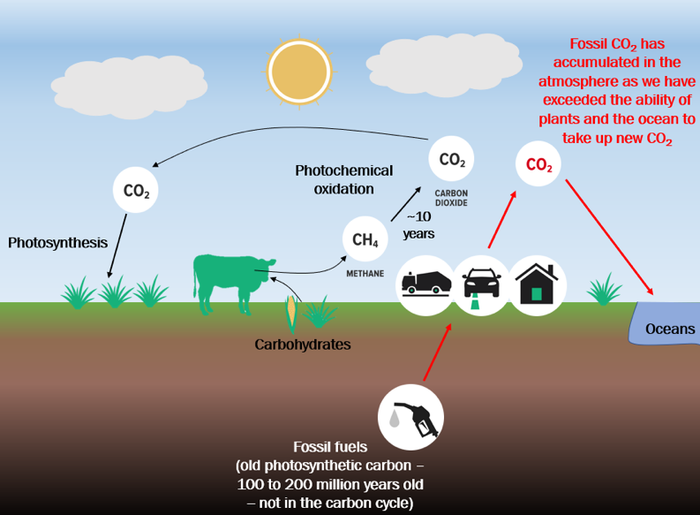

Cattle consume carbohydrates in plants like native grasses and corn grain. These carbohydrates contain carbon, the fundamental element of all living things, which is derived from carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere through photosynthesis.

When cattle eat carbohydrates, some of the carbon gets converted to CO2 and methane (CH4) by the rumen microbes. About once a minute, a series of rumen contractions releases this gas mixture from the animal’s mouth in a process called eructation, or more simply, belching. If this natural belching process doesn’t occur, cattle can suffer from bloat.

When the methane cattle release enters the atmosphere, it does have an effect of trapping heat energy. However, methane doesn’t stick around very long in the atmosphere.

Over the course of a decade, the methane emitted from a cow will be transformed through a series of photochemical reactions to carbon dioxide. That carbon dioxide can then again be taken up by plants, and the cycle repeats.

Research from Oxford University demonstrates that while methane is potent at trapping heat, if the emissions from a cattle herd are steady, the concentration of methane due to that cattle herd will not increase in the atmosphere. Ultimately, this is representative of the cattle situation in the United States and makes it difficult to point to methane from U.S. cattle as a key driver in increasing methane concentrations in the atmosphere or a key contributor to warming temperatures.

Globally, the situation may be different, as based on available information from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, it seems the global cattle herd has expanded. However, there are many methane sources that may explain the rising concentrations in the atmosphere, from other agricultural sources like rice cultivation to natural sources like wetlands. Another possibility is the increase in natural gas production and use (natural gas is mostly methane gas), and methane leaks from other fossil fuel production systems.

Importantly, carbon in fossil fuels is different than the carbon dioxide and methane that cattle emit, because it is not part of the natural carbon cycle. Fossil fuels are old photosynthetic carbon mostly from plants and algae from 100 to 200 million years ago.

When that carbon is released during the combustion of fossil fuels, the carbon dioxide emitted represents new carbon entering the system. Plants and the oceans have taken up some of this new carbon, but the rest has accumulated in the atmosphere; hence, the increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide we have measured since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

Figure 1. Simplified carbon cycle illustrating how methane (CH4) carbon is not additive to the atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) as compared to fossil fuel combustion. If methane emissions are constant and in balance with the rate of photochemical oxidation, methane concentrations will not increase in the atmosphere.

None of this is to say that we should ignore methane emissions from cattle. As Drs. Rotz and Hristov highlight in their fact sheet, mitigating methane emissions can mean improved feed efficiency of cattle as methane represents a loss of feed energy. Feeding concentrates, fats, ionophores, and new feed additives being developed can all mitigate methane emissions. Depending on the future, there may be the potential for carbon credits or other payment options for cutting methane emissions from cattle.

The methane cycle is complex. But, it’s critical to understand. Fifty-six percent of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with U.S. beef cattle production is the methane cattle naturally belch. Since it’s unlikely these emissions are driving warming, clearly communicating that a carbon footprint doesn’t always translate into climate change is a focus of the Beef Checkoff Program.

As Drs. Rotz and Hristov conclude, “Although cattle in the United States are not contributing to the increase in global warming and related climate change we are experiencing, they may be part of the solution.”

Sara Place, Ph.D., is senior director, sustainable beef production research, at NCBA, a contractor to the Beef Checkoff Program. She was previously assistant professor in the Department of Animal Science at Oklahoma State University. Raised on a dairy farm in Chenango County, N.Y., she received her Ph.D. in animal biology from the University of California, Davis, and her B.S. in animal science from Cornell University

Internal links within this document are funded and maintained by the Beef Checkoff. All other outgoing links are to websites maintained by third parties.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)