Cattle Health

thumbnail

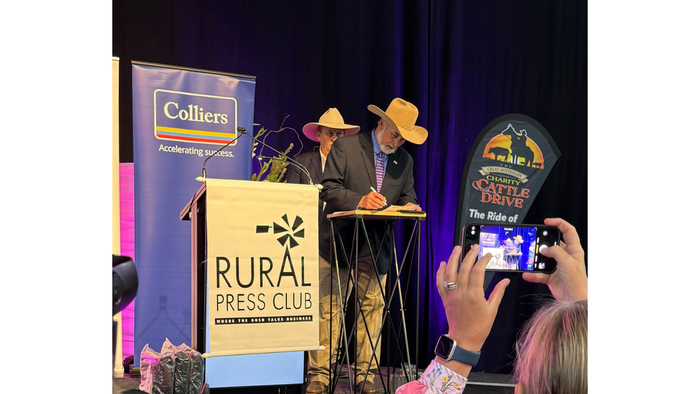

Livestock Management

Preparing cattle producers for foreign diseases such as FMDPreparing cattle producers for foreign diseases such as FMD

Extension program aims to reach 500 cattle producers to enhance biosecurity, mitigation.

Subscribe to Our Newsletters

BEEF Magazine is the source for beef production, management and market news.

.png?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)