How futures work: Position changes over time

It always takes two to tango. That��’s especially true in the futures markets. Our introductory class on the futures markets continues with position changes.

June 25, 2019

Throughout June, this column has been highlighting the essential fundamentals surrounding futures markets. That included a look at how to use both futures and options contracts for price risk management, primarily from the cattle feeding perspective, simply for example’s sake. And last week’s discussion highlighted the breakdown of positions among the various classes of market participants.

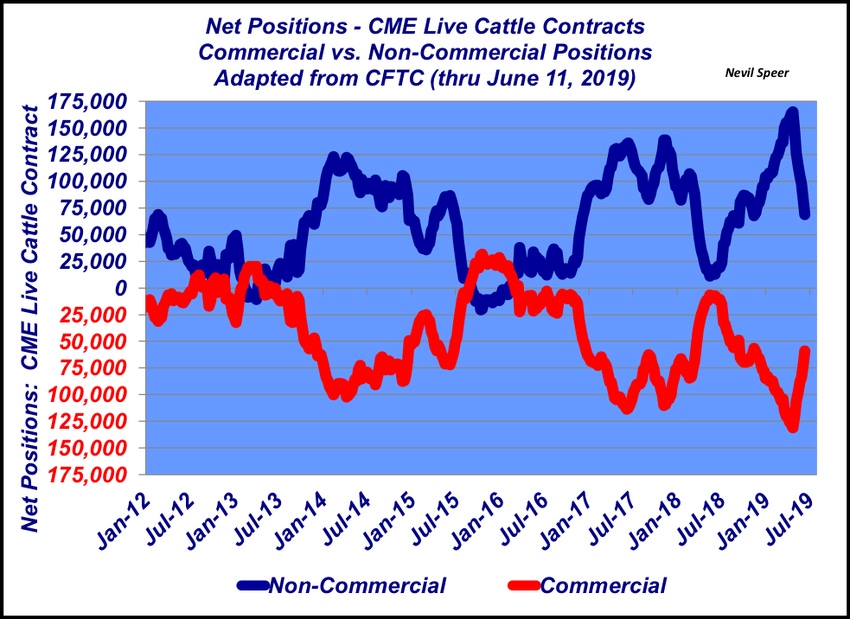

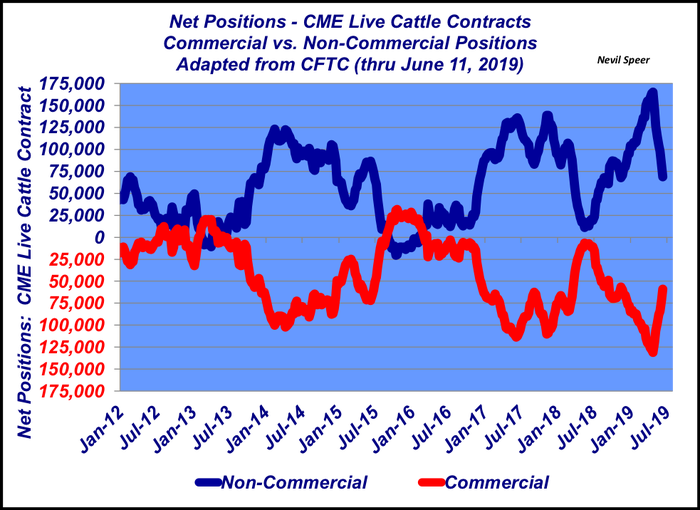

This week’s graph comes at the relative positions from a different perspective: It details the change in net positions (commercial versus non-commercial or hedger vs. speculator) for CME’s live cattle futures contracts over time. The net position is simply the sum of the short and long positions for each category of traders, commercial and non-commercial, respectively.

As a quick review, some basic definitions are helpful to better understand the graph:

Long: An initial buy position (obligation to accept delivery)

Short: An initial sell position (obligation to make delivery)

Speculator: Entity assuming pride to potentially profit from price change (non-commercial)

Hedger: Entity using futures/options market to manage price risk (commercial)

To that end, futures market theory works as follows: Speculators act as insurance providers, enabling hedgers to get price protection. The speculator (non-commercial) takes a long futures position with expectation that price in the future will rise.

The hedger on the other side wants to avoid downside price risk—he/she buys insurance from, and transfers risk to, the speculator. That happens by selling a contract at some given price below the “expected” price of the commodity in the future. Otherwise the hedger cannot induce the speculator to assume a long position – the discount being what the hedger pays the speculator for assuming risk.

As the graph details, those principles play out well for the live cattle contract. In fact, that’s been especially prevalent this past spring. In late April, the non-commercials (speculators) established a new record, being net long in excess of 165,000 contracts.

Meanwhile, the commercial (hedger) position was also a record; hedgers were net short by nearly 131,000 contracts. In other words, the hedgers were busy laying risk off to the speculators. That’s since moderated, but the net positions remain well in line with the general principles outlined above.

Last, there’s often lots of discussion around speculators coming in and out of the market and their relative influence on prices. That is, conventional wisdom often portrays speculators as driving the market higher if they’re buying contracts. If they’re selling, futures markets must be declining.

However, as noted last week, it’s important to remember there’s no limit to the number of contracts that can be traded – as such, more money doesn’t necessarily mean higher prices because futures contracts have no scarcity. Contracts are only established when a buyer can find a seller at a given price. Simultaneously, sellers can only unwind a position (leave the market) if/when participants on the other side allow them to do so. Hence, it always takes two to tango!

Speer serves as an industry consultant and is based in Bowling Green, Ky. Contact him at [email protected]

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)