Uncertainty rules as fed market weaves and bobs

Is the cattle market being manipulated? Or is working as it should?

September 12, 2019

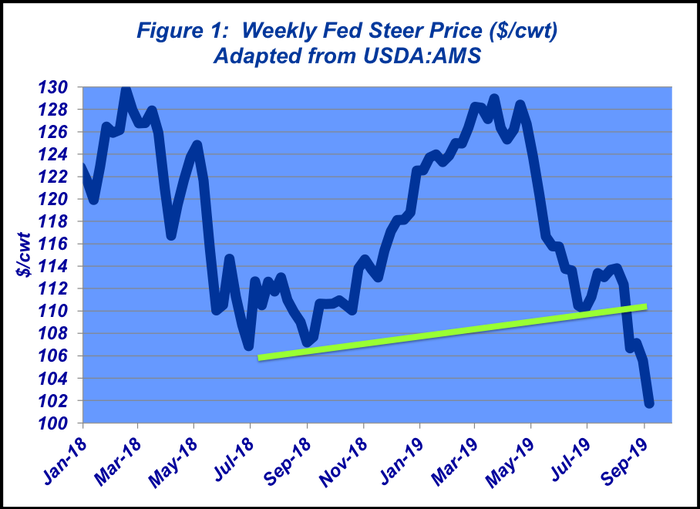

The phrase, “just when you least expect it,” sums up the frustration of the past four weeks. The market was trending in a good direction. Fed prices had bottomed at $110 per cwt in late June. From there, the market was working higher by trading largely $113-114 through much of July and into the first couple of weeks in August.

But then the unexpected happened. Tyson’s Holcomb fire was impossible to anticipate. Nevertheless, amidst a run of bigger volume and stronger prices, it was a gut punch and effectively reboots market dynamics for the foreseeable future. The fallout could prove to be significant over the long run, too.

Nevertheless, in line with expectations, in the weeks that’ve followed, the market has slipped all the way back to $100-$102 (Figure 1). Surprisingly, the year-over-year average through Labor Day still has 2019 about $1.50 per cwt ahead of 2018 – and on bigger volume.

However, that won’t last: The October and December live cattle contracts are now trading mid-to-upper $90s, respectively. If that’s any indication, it’ll be tough sledding at least through the end of the year.

Clearly, there’s a lot of work to do. However, the beef industry is proving its versatility.

The primary question in the days following the fire revolved around slaughter capacity. The packing sector never skipped a beat; it responded by altering schedules and got busy scheduling trucks. Consider the four weeks preceding the fire, the average Monday through Friday kill was roughly 601,000 head while Saturday’s throughput was nearly 46,000 head.

In the two weeks following the fire, weekday business dropped to 581,000 head while Saturday’s kill surged to average over 74,000 head.

Are packers the problem?

Meanwhile, lower fed prices and higher cutout values have fueled anti-packer sentiment within the industry. The diverging markets have called attention to packer gross profit trends since the fire – otherwise referred to as the live-to-cutout spread. (An overview was featured in last week’s Industry At A Glance.) All that said, the spread overstates what’s really happening from an accounting perspective.

It’s often referenced too broadly, with many simply calling it “profit.” More specifically, gross profit represents sales revenue less cost of goods sold. It does not account for operating expenses such as freight, salaries, wages, utilities, etc… (those considerations are taken into account by operating profit).

In other words, the live-to-cutout spread is parallel to feedyard gross profit; sales revenue from a fed steer less the cost of a feeder calf – and doesn’t account for feed and associated feeding costs. It’s not just “profit.”

It’s also important to note a couple of other factors where weekly calculation of packer gross margins don’t completely represent what’s occurring within the business. Primarily, there’s the issue of contracts and risk management.

That is, falling cash markets don’t imply lower prices across the entire kill due to prior contracts and/or hedging strategies. Moreover, the same holds true for the feeding sector - as noted in prior discussion, roughly 50% of the cattle on feed possess some sort of market protection because of risk management.

Then there’s the other side of the packing business, too. It’s evident some misperceptions exist regarding the ins and outs of the wholesale market. Despite claiming otherwise, packers don’t simply sell beef to their customers at some pre-determined price. For some context, consider that Tyson’s annual revenue last year was approximately $40 billion; beef operations generated $15.5 billion in sales.

Now consider the general market size of several key players on the buy side of the meat market. For example, Walmart generated $331.7 billion in U.S. sales last year with groceries accounting for 55% of that total ($184.2 billion). Meanwhile, No. 2 food retailer Kroger earned $121 billion of revenue during its previous fiscal year. Last, Sysco revenue in FY ’19 is projected to be just north of $60 billion. All this to clarify the market power of beef buyers; they’re anything but price takers when it comes to weekly negotiations.

The competitiveness on the beef side is best illustrated by a statement contained in Sysco’s FY ’18 10-K (annual report) – the company discussing the challenge of fighting for market share among their customers:

There are a large number of companies engaged in the distribution of food and non-food products to the foodservice industry. Our customers may also choose to purchase products directly from wholesale or retail outlets, including club, cash-and-carry and grocery stores, online retailers, or negotiate prices directly with our suppliers.

Packer profit vs. cow-calf profit

There’s also been some discussion regarding inflated packer gross profit and its enduring negative influence on upstream producers – most notably, cow-calf operations. That argument ostensibly makes sense. But the data doesn’t support those claims.

This week’s Industry At A Glance highlights the relationship between packer gross profit and cow-calf profitability dating back to 1990. The correlation is zero – in other words, cow-calf returns aren’t influenced by packer margins.

And then there’s the question as to why cattle feeders are willing to sell into a sharply lower market – one that’s allegedly being leveraged to the downside by packers. Consider a feedyard turns inventory twice per year or just slightly ahead of that rate; thus, each week’s business represents 4% of its inventory.

Disrupting that flow over the course of just a couple of weeks creates all sorts of logistic challenges - not to mention weakening its bargaining leverage in the weeks that follow if they don’t sell. Therefore, cattle feeders have great incentive to sell week-in, week-out no matter the market.

Nevertheless, the recent fire and subsequent packer gross profit trends have emboldened accusations of packer collusion and/or price gouging. Those are serious charges. Therein lies the need for some objectivity.

Dr. Jayson Lusk, Purdue University, explained it best in his blog, The Economics of Packing Plant Fires and Cattle Prices:

The packers may well be making more money, but these economic effects are exactly what one would expect even in a perfectly competitive market…In short, the effects we’re seeing right now in the beef and cattle markets are exactly what we’d expect from a textbook treatment of a reduction in wholesale supply in a vertically linked market.

Given the recent turn of events, the most important take-away is to emphasize the need for careful, objective, data-driven analysis. Time and effort acquiring and reviewing such information is essential! It leads to increased likelihood of good decision-making and laying the foundation for business success.

And as noted several weeks ago, “The beef business is inherently challenging and requires careful management of one’s business against potential shocks from the outside.” Strategic risk management – around all facets of your business - has never been more important.

Speer serves as an industry consultant and is based in Bowling Green, Ky. Contact him at [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)