Welcome to Health Ranch, where you can find information and resources to help you put the health and well-being of your cattle at the top of the priority list.

Managing liver flukes takes a specialized deworming approach

Understanding the life cycle and risk factors can guide a control plan

August 1, 2023

Once confined to the moist environments of the Gulf Coast and Pacific Northwest, liver flukes are now found in 26 states because of modern movement of cattle, wildlife and hay, as well as shifting rain patterns. There are few dewormers that are effective against liver flukes, so working with a veterinarian is key to understanding the fluke’s life cycle and risk factors, as well as building a parasite control plan aligned to the needs of your operation.

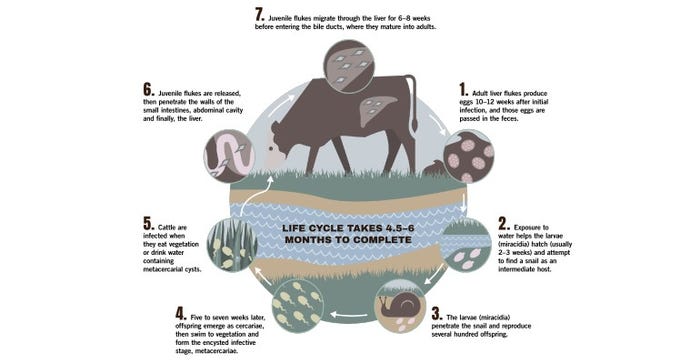

The liver fluke is one of the more complex parasites to infect beef cattle. Its life cycle (see Figure 1) typically takes five or more months, it is reliant on an intermediate host, and it is difficult to detect prior to causing damage.

Figure 1. The Liver Fluke Life Cycle

Image Submitted by Boehringer Ingelheim

“Most people don’t realize there’s an intermediate host involved,” explained DL Step, DVM, Boehringer Ingelheim. “It’s an eye-opener for them. The larva migrates to a freshwater snail, where it can multiply. When it exits the snail, cattle can ingest it by drinking infested water or consuming infested grass.”

While many point to liver flukes as being dependent on wet environments, the main culprit is the snail. “Flukes are more prevalent in moist environments because that’s where the snail prefers,” Dr. Step remarked. “But a snail can also help flukes survive dry conditions by burrowing into the mud.”

Since host snails are drawn to water, it might seem obvious to keep cattle away from ponds, wet pastures and low-lying areas where water may collect. However, cattle and snails are drawn to any water source, including water troughs, so monitoring cattle for signs of infection and integrating diagnostic practices can help determine if and when parasite control is warranted.

Assessing signs of infection and timing diagnostics can be tricky

A liver fluke infection may go months before clinical signs become apparent and diagnostics indicate infection. Cattle origin also plays a factor in fluke incidence. If you’ve purchased cattle from out of the area, determine if they originated from an area where flukes are prevalent to help understand risk level.

It can take at least two months for flukes to evolve from egg to the juvenile phase, which is when they penetrate the walls of the small intestines, abdominal cavity and, finally, the liver. The liver is where they earn their name — liver flukes — because they do the most damage to the liver, spending six to eight weeks there before maturing into adults that produce eggs, which are passed in feces.

“Signs often depend on level of infection,” Dr. Step noted. “Normally, they’re more ongoing, chronic signs, such as ill thrift, loss of appetite, rough hair coat, decreased performance, weight loss and poor reproductive efficiency. We have an acronym to describe it: ADR, or ain’t doing right.”

Besides monitoring cattle for signs of infection and wet areas for snails, you can work with your veterinarian to devise a diagnostic and parasite control plan for liver flukes. There are several factors to keep in mind that can cause complications:

Juvenile flukes cause the most damage but are difficult to control with available treatments; whereas adults are easier to control but cause little damage.

Diagnostics, like a fluke sedimentation test, are used to look for fluke eggs that are passed in the feces.

The fluke’s life cycle can take at least five months for the adults to produce eggs, which means if you perform diagnostics too soon, you may receive negative results and need to retest.

Your veterinarian will be familiar with these risks and the history of your operation, enabling them to develop a plan that aligns best to the needs of your cattle. Depending on the environmental conditions, that could mean a treatment in late summer or fall with a special compound called clorsulon.

“It’s always a best practice to work with your veterinarian on a regular basis to assess the health and well-being of the herd, develop protocols for that time of the season, and then stay in contact with the veterinarian to provide updates on the progress of animals and timing of protocol administration,” Dr. Step concluded.

©2023 Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc., Duluth, GA. All Rights Reserved. US-BOV-0170-2023

You May Also Like